INTRODUCTION

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSKD) include more than 150 diagnoses that affect the locomotor system of individuals. MSKD are initially recognized by musculoskeletal (MSK) pain, and then secondarily, by limitations in mobility, motor control, dexterity, and general function. They range from disorders that arise suddenly, such as fractures, sprains, and strains, to chronic conditions contributing to functional limitations and disability.1 Often the muscle, bone, or joint condition is mechanical in nature as is the case in osteoarthritis. Additionally, disorders affecting the body’s inflammatory process are included, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, gout, and ankylosing spondylitis. World-wide, the most common MSKD reported are low back pain and osteoarthritis.2 MSKD are on the rise around the world.3 The total number of MSK-related disability-adjusted life years have increased by 25% from 2000 to 2015 with MSK diseases being the second cause of years lived with disability worldwide. MSKD are known to contribute to significant mental health decline, cluster around common chronic diseases and increase all-cause mortality.3

MSKD are the highest contributor to the need for rehabilitation across the globe with two-thirds of all adults in need of rehabilitation.4 More than one in two adults in the United States (US), 124 million over the age of 18, report a musculoskeletal medical condition. That exceeds the next two most common health conditions including circulatory conditions (such as heart disease, stroke, and hypertension) and respiratory conditions.5 Across all adult age categories, MSKD are either the most reported medical conditions (among those < 65 years old) or second most reported (among those 65 years and older). In 2015, 36% of the US adult population reported difficulties performing routine activities of daily living (ADLs) due to a medical condition. Of those adults reporting ADL limitations, 64 million had a concomitant musculoskeletal condition. Individuals in the US population with an MSKD are likely to have other associated conditions and comorbidities, affecting health overall and complicating the MSKD diagnosis and treatment process.6

A recent survey conducted in Australia7 focused on the impact of MSKD on the population and described similar results with an estimated seven million adults affected by chronic and painful MSKD. Of those affected, 57% report two or more MSKD, 66% indicated their condition had an adverse effect on their family and personal relationships, 72% report adverse effects on sleep, and 50% report a negative impact on their mental health. Additionally, MSKD can severely disrupt work for adults since 58% affected are in their prime working years between 25-64 years of age. In the United States, low back and neck pain are the most expensive health conditions, estimated at $134.5 billion. As this condition often occurs in the working-age population, the indirect costs, including disability benefits and days of work missed, are estimated to be as high as $624.8 billion.8

Considering millions of people seek rehabilitation currently, aligning rehabilitation professionals to focus on identifying the most prominent MSK risk factors for everyone under their care through a standardized operating procedure could be helpful. While prevention and physical activity promotion are clearly within the scope of the rehabilitation provider, efforts in these domains are falling short.9 Most patients conclude their rehabilitation program with little knowledge of the value of physical activity, without the awareness of their most prominent risk factors for MSK health and prevention.

Known strategies to prevent and treat MSKD are generally described around increasing physical activity levels. Good MSK health habits, like smart exercise, have an abundance of positive effects from decreased obesity to improved mental health and reduced pain.10 But, simply suggesting an individual with a MSKD become more active may not be an adequate solution. While most individuals are aware of the benefits of physical activity and exercise, many are unable to engage in routine physical activity because of existing MSKD pain. Approximately 76% of adults with an MSKD report that it directly limits their physical activity.7 Although increased physical activity is a proven way to decrease the prevalence of all-cause mortality risk factors and improve overall health, physical inactivity seems to be on the rise,11 and trends suggest MSKD are a contributing factor. While efforts focused on behavioral change can be helpful to increase activity level for some individuals12 a concurrent consideration for current MSK health status and risk should be considered as well.

There is a tremendous burden associated with MSKD directly and, because of their attenuating effect on physical activity levels, MSKD are also a silent contributing factor to the well-established chronic diseases that make up metabolic syndrome.13 In 2015, Carlson et al. noted that 11.1% of all health care costs were associated with “inadequate” physical activity and that this is on the rise.14 Theoretically, addressing MSKD by identification and management of common risk factors could result in improved physical activity levels, decreased injury rates, and less overall financial burden. Therefore, the primary purpose of this review is to describe the known risk factors most closely associated with MSKD. The secondary purpose is to propose a clinical model to manage MSK health aimed at maximizing the healthy pursuit of a physically active and healthy lifestyle.

WHAT ARE RISK FACTORS?

A health risk factor is anything that increases a person’s chances of getting a disease or other health-related condition.15 Risk factors are well established for many life-threatening conditions present in adults such as cardiovascular disease. But there is little public health focus on risk factors associated with MSKD, which is surprising given the massive burden MSKD have on our society.1,2,5 In this commentary the authors discuss risk factors that have been associated with the development of MSKD overall and discuss strategies that may help to manage these risk factors more effectively. Perhaps, if risk factors for MSKD are managed more effectively, the burden associated with MSKD will be reduced.

MSKD are multifactorial and a good understanding of the key risk factors and conditions associated with MSKD is important. While most MSK risk factor research has focused on MSK function or a singular injury, researchers now have demonstrated the multifactorial nature of MSKD and the specific risk factors associated with the overall development of MSKD in adults.16 For example, individuals with behavioral health needs are at greater risk for MSKD17,18 as are those who have had a recent MSK injury.16,19,20 A previous injury within the prior 12 months is a known strong risk factor,19 but also the magnitude of that injury16 as well as the self-perception of recovery16,20 from that injury are also independent risk factors that deserve consideration in an individual’s overall risk profile.

Recent research has shown that individuals with multiple risk factors are at increased risk for MSK injury16,21,22 and have reduced physical performance.21 Not surprisingly, there is a linear relationship between the number of risk factors and injury risk.16 The more risk factors that an individual has, the more likely they are to ultimately develop an MSKD. Therefore, it may be important to screen for MSKD risk factors, to consider the presence of multiple risk factors, and the combinations of these factors to establish everyone’s overall risk level. Screening can help to determine the most important domain of MSK health which should be prioritized and provide rationale and guidance for direct intervention for those at greatest risk. For example, it is well known that individuals with higher BMI are at greater risk for OA. But, simply sharing this with a patient and expecting changes in exercise and diet to address high BMI is not likely to be an effective strategy.23 Perhaps employing a screening process that prioritizes risk factors for MSK health, with a focus on the most prominent and modifiable areas could be helpful. When key risk factors are screened for and considered together, an appropriate migration strategy can be developed, in conjunction with the patient’s current rehabilitation program to enhance and promote overall MSK health.

RISK FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH COMMON MSKD

Comprehensive review of the literature has resulted in the summation of the risk factors most closely associated with overall MSK health. These risk factors can be identified through the MSK screening process in clinical practice as routine annual wellness check-ups or throughout the course of rehabilitation. Like cardiovascular risk factors, MSK risk factors are interrelated suggesting that healthcare professionals must systematically evaluate the entire profile of an individual. For example, a previous ankle sprain injury where the ankle dorsiflexion ROM was not fully restored could potentially result in another ankle sprain or possibly an injury to the knee. Furthermore, reduced ankle mobility will have negative effects on functional movement (i.e. squatting, stepping, lunging) and dynamic balance which could limit the individual’s ability to be physically active, resulting in poor cardiovascular fitness, increased BMI, and suboptimal psychological status. Restricted ankle dorsiflexion does respond favorably to direct intervention and/or education when appropriately identified and administered. The following are key MSK risk factors, presented alphabetically.

Ankle Dorsiflexion ROM

Asymmetrical ankle dorsiflexion of at least 4 degrees has been identified as a significant risk factor for time loss injury in military and sport populations. Asymmetrical ankle dorsiflexion has been identified as a risk factor for future falls in elderly populations.16,24,25

Body Mass Index

High body mass index has been associated with increased risk of sustaining an injury in military and sport populations. High body mass index has also been identified as a significant risk factor in future osteoarthritis and total joint replacement.26–30

Cardiovascular Fitness

Decreased cardiovascular fitness has been identified as an independent risk factor for future time loss injury in military, sport populations, and elderly populations.16,30

Dynamic Balance

Impaired dynamic balance has been identified as a significant risk factor in future time loss injury for military and sport populations.16,24,31

Functional Movement Competency

Impaired functional movement (measured by the Functional Movement Screen and the Selective Functional Movement Assessment) has been identified as a significant risk factor in future time loss injury for military and sport populations.30,32–36

Muscle Strength

Decreased muscle strength has been identified as an independent risk factor to sustain a future injury in sport and elderly populations.10

Pain with Movement

Pain with movement was identified in three separate military populations as a significant risk factor in future time loss injury.16,24,30

Perceived Recovery

Perceived recovery as measured by the Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) score following an injury was identified as an independent prospective risk factor for future injury. Individuals who report their SANE score following an injury at <92% were shown to be more likely to sustain a future time loss injury.16

Physical Activity

Low physical activity has been identified as a significant risk factor for the development of osteoarthritis and sustaining a fall in elderly populations.27

Previous Loss Time Injury

The presence of a previous time loss injury has been identified in multiple studies as an independent and robust risk factor. Additionally, the magnitude of the injury, as measured by the number of days missed, has also been identified as a risk factor for future injury.16,19,24,37

Psychological Status

Diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression has been identified as an independent significant risk factor in musculoskeletal pain or injury.17,18,38

CLINICAL MODEL

There is a need for a modern and innovative model to approach MSKD. The MSKD health problem is extremely complex requiring management with more than one tactic. However, the first step in addressing this large-scale problem is identifying known risk factors and providing individuals with awareness of the biggest limiting factors impacting their own MSK health.

Consideration of the number of risk factors present and the magnitude of each factor is contemplated in the overall care of the patient. With a good understanding of a patient’s current risk, a comprehensive rehabilitation plan can be executed to mitigate the impact that risk factors have on overall physical activity and function. This approach is a more systematic and comprehensive model to evaluate MSK health, rather than a purely pathoanatomical approach where treatment is dictated simply by current symptoms or medical diagnoses. In a recent study conducted in 18–45 year-old adults, the researchers captured multiple physical performance measures and known MSKD risk factors at time of discharge from rehabilitation for lower extremity or spine dysfunction.39 This entire sample of 469 subjects had been cleared to return to full activity by their healthcare professional. The researchers found that over 70% of the sample had at least five known MSKD risk factors at time of discharge and 44% had pain with global movements. This does not include the obvious previous injury that was an inclusion criterion for the study. In this case, local pain was managed well, but these data demonstrate the need to expand conventional rehabilitative care to include comprehensive risk factor management.39

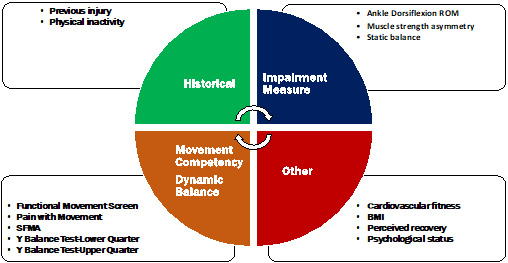

There are a variety of evidence-based approaches that are utilized by rehabilitation providers to directly address the pain and disability associated with a given MSK condition. It may seem overwhelming to add MSKD risk factor management to current models, but a commonsense approach that optimizes a standardized process is the key to establishing MSKD risk factor management into current rehabilitation practice. When the most prominent and modifiable risk factors are considered rather than each one individually, the process becomes attainable. It can be as simple as screening for functional movement40,41 (including presence of pain), ankle mobility42,43 and balance44,45 which is approximately a 15-minute investment. Risk factor screening can occur as part of the standard physical therapy examination or can be executed in the early phases of the rehab process. The timing of screening will be somewhat dependent on the acuity and nature of the primary condition the patient is being seen for. Ultimately, the plan of care should include intervention targeted at the most prominent risk factors as well as a discharge plan that addresses ongoing risk factor management. (Figure 1).

ADDRESSING RISK FACTORS

Evidence-based interventions, prescribed to address identified risk factors, can be integrated into the locally focused rehabilitation program, and built into the program progression. In a study by Schwarzkoph-Phifer et al46 that measured risk factor management during rehabilitation, it was demonstrated that with traditional interventions focused on manual therapy and therapeutic exercise, the number of risk factors present following the intervention period was significantly reduced with an average reduction of three risk factors. In another study by Huebner et. al. it was demonstrated that overall MSK risk category can change significantly from higher risk to lower risk with individualized interventions.47 A combination of manual therapies and therapeutic exercise has been shown to improved ROM and dynamic balance in subject with ankle dorsi-flexion restrictions.48–50 Individualized therapeutic exercise programs have been shown to significantly improve functional movement abilities when compared to control subjects,51,52 and dynamic and static balance has been shown to improve in multiple studies with a variety of interventions across different age groups.53,54

Awareness of the number of risk factors is also considered. Some individual factors are in and of themselves nonmodifiable, making it even more important to address the factors that are amenable to intervention, to reduce overall risk. Additionally, some patients may benefit from referral for professional help with areas such as behavioral health or to a training specialist for help with cardiovascular fitness and/or strength training. Organizing risk factors by category can help the clinician clarify which risk factors to intervene on and provides a risk factor profile to help understand each patient’s prognosis. (Figure 2).

A thorough understanding of each patient’s individual risk profile at discharge time can help to instill confidence in the therapeutic relationship and serve to provide clear guidance to the patient of what they should be working on to maximize their MSK health and benefits gained from a physically active lifestyle. As clinicians become more comfortable with this full body, risk factor approach, it simply becomes how they practice rather than a disconnected portion of the program that is added on near the end.

CONCLUSION

MSKD are the leading contributors to disability worldwide and present a substantial burden to healthcare systems. Unlike other prevalent and disabling healthcare conditions, risk factors associated with MSKD are not commonly discussed or integrated into current medical practice or wellness programs. In this review the authors describe the most common MSKD risk factors, and it is suggested that addressing known risk factors for MSKD in rehabilitation may be an important factor moving forward to reduce the enormous and growing burden these disorders are having on society.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Kiesel and Dr. Plisky report a relationship with Functional Movement Systems where they own stock. Dr. Arnold is a compensated instructor for Functional Movement Systems. The other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.