INTRODUCTION

Hip and groin problems are a common concern among athletes participating in multi-directional team-sports involving high-intensity, repetitive, and forceful hip movements.1–3 Movements such as kicking, skating, and rapid changes of direction can lead to trauma or overuse, causing pain around the hip and groin area and long-standing and debilitating conditions1–5 that may affect sports participation and performance.6,7

Hip and groin problems are particularly common in professional male athletes, with high prevalence reported in soccer players ranging from 21-59%7–11 and 12-29%9,12 for seasonal and weekly prevalence, respectively. In addition, seasonal prevalence of hip and groin problems of 53% have been reported in professional ice hockey players,13 while other sports such as basketball, Australian football, and field hockey have reported prevalences ranging from 17% to 22%.8,14,15 In contrast, there is less research examining the epidemiology of hip and groin problems in female athletes. Studies in female football (soccer) and ice hockey, report a cumulative prevalence of 27-45%9,16,17 and 62%,18 respectively. Additionally, to date, very few studies have applied the Doha Agreement classification system to this population17 or examined the association between hip and groin function and hip muscle strength. As women’s sports continue to grow rapidly in popularity and the number of professional athletes is increasing, it is crucial to address this gap about hip and groin problems in female athletes.

Hip and groin problems can be classified as either time-loss or non-time-loss, depending on whether the athlete is able to fully participate in training and competition despite the problem. While time-loss injuries account for only a small proportion of all groin problems in elite and sub-elite athletes (9-38%),9,12,13,16,19,20 it is essential to examine non-time-loss problems to better appreciate the overall burden of hip and groin pain.

Factors such as previous groin injury, higher level of play, reduced hip adduction strength, and lower levels of sport-specific training have been associated with increased risk of groin injury in sport.21–23 Higher body mass index, age, and reduced hip range of motion (ROM) have also been reported as intrinsic risk factors for groin injury, although with conflicting evidence.21–23

The inconsistent use of terminology and classifications in the literature and the complexity of the clinical examination can make diagnosing hip and groin problems in athletes challenging.24 To address this, the Doha Agreement meeting proposed a classification system to clarify and standardize terminology and clinical taxonomy.25 Accurate and standardized classification can enhance the comprehension of these problems and improve the quality and synthesis of research to improve management and prevention strategies.24 Previous research in male athletes using the new taxonomy has shown that most groin problems are classified as adductor-related groin pain,10,11,14,20,26 as did a recent study in female soccer players.17

The purpose of this study was to examine the preseason point prevalence of hip and groin problems in elite female team-sport athletes. Secondary aims were to categorize the groin problems according to the Doha Agreement classification system and to explore the association between hip muscle strength and self-reported hip and groin function.

METHODS

Study Design

This project was an exploratory, observational, cross-sectional cohort study.

Settings

This research project was conducted among female team-sport athletes competing in the highest league of their respective sport (basketball, floorball, handball, ice hockey, soccer, and volleyball) during the 2022/2023 preseason in Switzerland, as this appears to be the period with the greatest exposure to hip and groin problems.27,28

Ethical approved for the study was provided by the Zurich Ethics Committee (ID# 2022-00409).

Experimental Procedures

Recruitment

The recruitment period for the different teams ran from April to June 2022, and the data were collected in the summer of 2022 within the first three weeks of each sport’s preseason: June for ice hockey, July for floorball and soccer, August for handball, and September for basketball and volleyball.

The study coordinator contacted the managers of 20 teams verbally or by e-mail to provide them with an overview of the study and an information sheet detailing its objectives. After receiving verbal or written participation confirmation, an informed consent form was sent to the manager for distribution to the athletes. The manager then introduced the project to the athletes and ensured that each participant understood the voluntary nature of their participation and their right to withdraw at any time during the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation.

Included participants underwent a two-stage assessment. First, all players underwent hip adduction and abduction muscle strength assessment and completed the Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS) to describe their hip and groin function. Secondly, those players who reported hip and groin problems underwent a full standardized clinical hip and groin examination (further described in the Clinical Entities section). All assessments were performed by two physiotherapists (JDS, FR) who were trained in the assessment procedure.

Participants

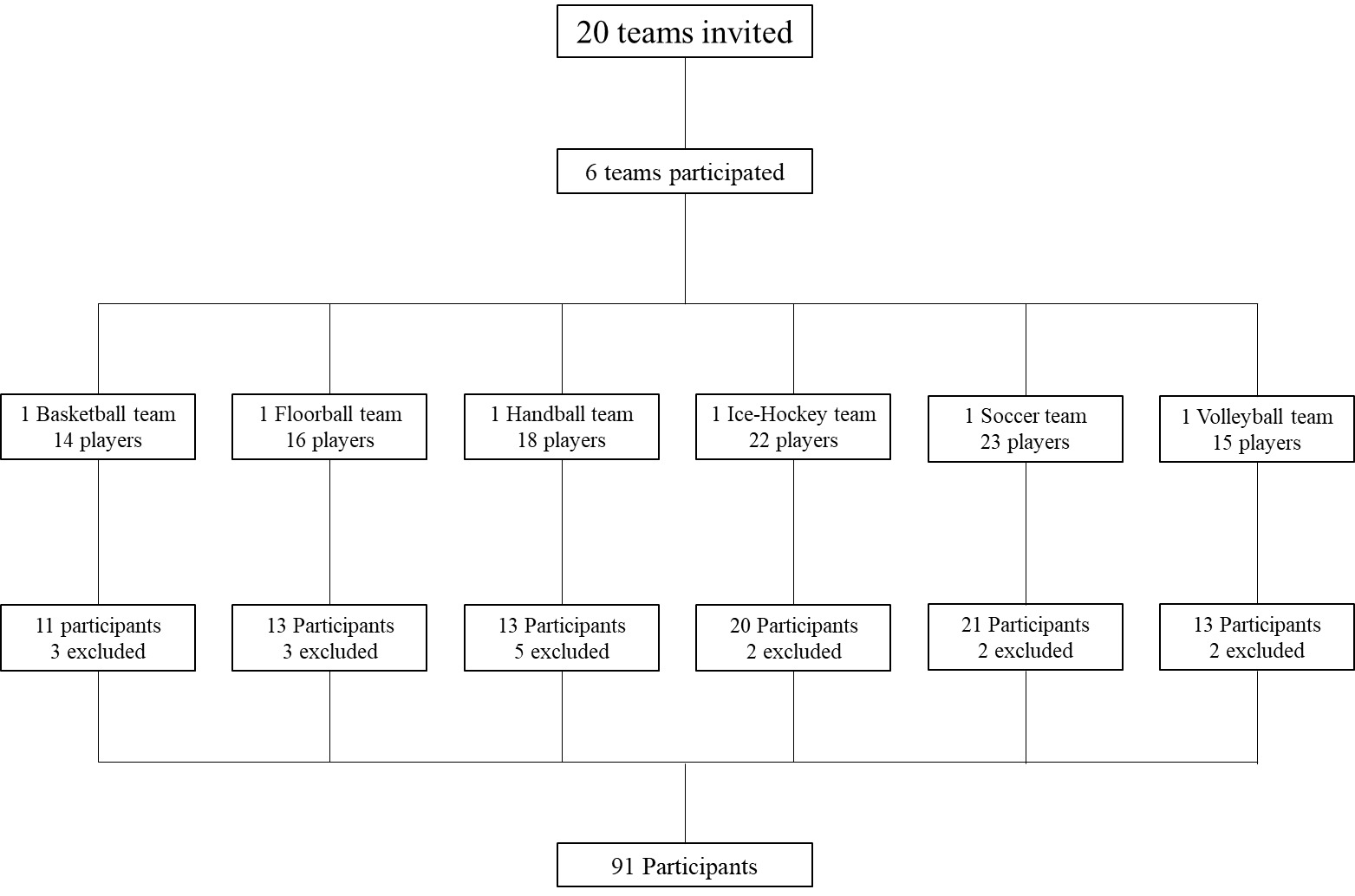

Out of possible 20 team, six teams from six different sports agreed to participate in the study, and participants were included based on the criteria outlined in Table 1.

Study Outcomes and Measurements

Stage-1 Measurements

The following assessments were conducted during the first phase of data collection.

Participants’ Characteristics

All participating athletes were asked to provide personal information, including their age, height, weight, sport, playing experience (measured as the number of years competing at the highest level), and dominant leg (defined as the preferred leg for kicking, regardless of the sport).

Hip Muscle Strength

Hip adduction and abduction muscle strength was assessed isometrically in the supine position (with 45° of hip flexion and 90° of knee flexion) by means of a measurement device (ForceFrame, Vald Performance, Albion, Australia) that has been shown to be valid and reliable for the assessment of hip muscle strength.29,30 The strength measurement protocol used in this study was based on the methodology described by Oliveras and colleagues and is detailed in Appendix A.31

Briefly, participants were first asked to perform a submaximal contraction of each muscle group for warm-up and familiarization purposes. Then, they completed three bilateral maximal voluntary contractions of the hip adductor and abductor muscles. The assessment order for the two muscle groups was randomized to avoid systematic bias. Only the highest peak force trial was retained for each muscle group and side. The primary outcomes were absolute and relative (normalized to body weight) hip abduction and adduction strength, and the ratio of hip adduction to abduction strength for each side. For the analyses, the average of the left and right side was calculated for participants without pain or with bilateral pain, while only the value of the affected side was used for participants with pain.

Hip and Groin Pain

Immediately after each contraction of the strength tests, athletes were asked to rate their groin pain using a 0-10 Visual Analog Scale (VAS), where 0 and 10 corresponded respectively to no pain and maximum pain, and to indicate which side was painful (right, left or both). A cut-off score of >2 was used to differentiate between players with and without pain.32,33

Before the strength tests, hip and groin pain was also assessed using a subjective complaint question20: “Have you recently had hip or groin pain that has limited your performance while doing your sport?”. If the answer was positive, an additional question was asked: “Which limb was symptomatic (dominant, non-dominant, both)?”. Hip and groin pain was defined as any physical symptom located in the groin region that prevented a player from fully participating in training or match or reduced performance in the previous week.

Hip and Groin Function

Hip and groin function was measured using the HAGOS, a self-report questionnaire that has been validated for assessing hip and groin disability and is recommended for use in young to middle-aged individuals.34 It consists of 37 items divided into six subscales assessing: symptoms, pain, physical function in daily living, physical function in sport and recreation, participation in physical activities, and hip and/or groin-related quality of life. Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4, with 0 indicating no hip and groin problem and 4 indicating extreme hip and groin problems. Subscale scores range from 0 to 100, with 100 indicating no hip and groin problems and 0 indicating severe hip and groin problems. The questionnaire has been found to be reliable, internally consistent, and valid in young athletes.35

The most interesting and relevant subscale for team-sport athletes is the sport subscale because it focuses on activities such as sprinting, twisting/pivoting, and kicking.32,36 Based on previous studies, a cut-off score of <86 was used on the sport subscale to differentiate between players with and without problems.20,32

Definition of Hip and Groin Problem

Participants were defined as having hip and groin problems and assessed for a complete clinical examination of the hip and groin area if that had at least two of the following responses: VAS score >2 during hip muscle strength tests AND/OR a score of <86 on the HAGOS sports subscale AND/OR a response of “yes” to the Subjective Complaint Question. These defined criteria were based on a previous cross-sectional study conducted in athletes.32

Stage-2 Measurements

Following the guidelines of the Doha Agreement classification system, a clinical examination protocol was conducted to assess the hip and groin area. The assessment was performed by a physiotherapist (JDS or FR) trained specifically for the protocol.

Clinical Entities

The clinical entity approach consists of categorizing the hip and groin problems using standardized, reproducible examination techniques and classifying the problems into four defined clinical entities: (1) adductor-related, (2) iliopsoas-related, (3) inguinal-related, (4) pubic-related groin pain, and the two additional categories of: hip-related groin pain or other (Table 2).6,25,37 The examination is preceded by a screening to exclude causes other than hip and groin.38 The intra- and inter-observer reliability of several elements of this physical examination approach are acceptable for use in practice.25,39 Since the definition of the iliopsoas-related clinical entity is open to interpretation, prevalence rates were calculated with “tenderness” as the only criterion, and also with “tenderness AND pain on resisted hip flexion AND/OR pain on hip flexor stretching” as the criteria.

Prior to the assessment, the two physiotherapists who conducted the examination (5 years of clinical practice) were trained by two other experienced physiotherapists (MB, RFB) to perform the clinical examination using the above-mentioned protocol. The examination was always performed bilaterally (randomized order) and the time available for the entire testing procedure was approximately 15 minutes per subject.

According to the Doha Agreement, tenderness was defined as discomfort or pain felt on palpation of the area and identified by the athlete as her specific pain.25

The detailed examination protocol is described in Appendix B.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables (participants’ characteristics data, hip strength) are described using means and standard deviations (SD), ordinal variables (HAGOS subscale scores) using medians and interquartile ranges, and categorical variables (prevalence) using numbers and percentages. For all variables, comparisons between the participants with vs without hip and groin problems were made using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests due to unequal group sizes and non-normally distributed data, with a significance level of less than 0.05 or 0.001, as indicated. Box plots were generated to illustrate between-group comparisons for strength and functional parameters. The overall point prevalence of hip and groin problems was calculated by dividing the number of participants with hip and groin problems by the total number of participants. For the calculation of the hip-related entity prevalence, only athletes with clear hip-related pain as a single entity were reported, as highly specific tests to include hip-related pain have not been described.40

The strength of association between hip adductor/abductor strength and hip function (each HAGOS subscale) was estimated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. Correlations were arbitrarily interpreted as negligible (0.0-0.10), weak (0.10-0.39), moderate (0.40-0.69), strong (0.70-0.89), or very strong (0.90-1.00).41All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.2.2, R Core Team 2022).

RESULTS

Complete participants’ characteristics data, hip adduction/abduction muscle strength, and hip and groin function data were collected from 91 participants from six different team sports in Switzerland (Figure 1, Table 3, detailed strength and function data in Appendix C).

Prevalence

The overall point prevalence of hip and groin problems was 14.3% (n=13). The prevalence for each sport was 30.8% for volleyball, 20.0% for ice hockey, 14.3% for soccer, 7.7% for floorball, and 0% for basketball (Table 4).

Of the 13 participants with hip and groin problems, one participant withdrew from the study (absent on the day of measurement) leaving 12 participants who underwent the complete clinical examination. Among these 12 participants, there were a total of 17 clinically defined entities, with three cases of bilateral groin pain, seven cases of single entity, and two cases of multiple entities (two entities). There were three cases of hip-related groin pain, and there were no cases defined as ‘other’. The clinical entity-specific prevalence, calculated by dividing the number of a given entity by the total number of entities, was 58.8% for iliopsoas-related, 11.8% for adductor-related, 5.9% for inguinal- and pubic-related groin pain. The hip-related groin pain prevalence was 17.6% (Table 5). Detailed information on distribution of clinical entities by sports can be found in Appendix D.

Participants’ Characteristics, Strength, and Function Data

No group differences were found between the participants with and without problems in participants’ characteristics data, absolute and relative hip abduction and adduction strength, or hip adduction to abduction ratio (all, p>0.05, Tables 6 and 7).

However, the two groups differed in all HAGOS subscales (p<0.001) (Appendix E).

Internal and external rotation hip ROM were recorded for the 12 participants in the hip and groin problems group. Due to the insufficient sample size, no statistical analysis was performed.

Strength-Function Correlation

No associations were found between hip strength and hip function (Table 8).

DISCUSSION

Prevalence

Of the 91 female athletes included in this study, 14.3% were found to be affected by hip and groin problems in preseason assessment. This represents a non-negligible proportion as these are athletes who train “normally” but have impairments that could affect their performance.

Studies investigating the prevalence of hip and groin problems in female athletes are limited and diverse in methodology.9,16–18 In addition, the published literature mostly refers to a time-loss definition of hip and groin problems and included athletes from only one sport, making it difficult to compare with the current findings.

Of the studies that investigated a female athlete population, Wörner et al.18 conducted a study of 69 elite female ice hockey players, reporting a seasonal prevalence of hip and groin problems of 62%. The study was conducted retrospectively over an extended period based solely on self-reported questionnaire results, and reported a cumulative prevalence, which may explain the high prevalence values compared to this study. Caution should be taken when comparing the results of the current study with those of Wörner and colleagues, because they defined seasonal prevalence as having experienced at least one hip and groin problem in the previous season, so that 62% represents the cumulative proportion of hip and groin problems. Therefore, it cannot be compared with the findings of this study, in which the prevalence referred to a specific time (point prevalence). Similarly, Langhout et al.16 reported a cumulative prevalence of hip and groin problems of 27% in the preseason (eight weeks) among 434 amateur female soccer players, using an online self-reported questionnaire. This is a lower value than the one reported by Wörner et al.,18 probably given the shorter period assessed, but again it is not comparable with the values of this study. Haroy et al.9 with a six-week prospective study reported a cumulative prevalence of 45% and an average weekly prevalence of 14% among 45 elite female soccer players. The results of the present study seem to be consistent with those of Haroy and colleagues. In a recent paper, Thorarinsdottir et al.17 report a cumulative prevalence of 42% and a weekly prevalence of 4% in a two-season prospective study in female soccer players. This study reported a time-loss injury rate of 80%, which may indicate that less severe cases of hip and groin injuries were not identified, thus possibly explaining the 4% weekly prevalence.

The accuracy of diagnosing hip and groin problems is influenced by data collection methods, observation period length, and assessment criteria. Retrospective studies using self-reported data can be less accurate due to recall bias. The length of observation impacts precision in prospective studies. Criteria for defining hip and groin issues affect prevalence calculation, possibly leading to over/underestimation. The aforementioned studies mainly used questionnaires based on past events, where subjective factors such as personal experience, pain perception and emotions could potentially affect recall. Since the aim of this study was to define the point prevalence as accurately as possible, a combination of three criteria for past and present events was used, adding a pain reproduction test. As shown in Table 4, this resulted in lower percentages, but seems to have led to a more accurate selection of subjects with hip and groin problems, since all HAGOS subscales (and not just the sport subscale) showed a significant difference between the hip and groin problem and no problems groups, thereby indicating discomfort in all aspects of daily life and a real burden.

Several research studies have been published on hip and groin problems in males, with varying prevalence’s depending on the sport and level of practice.7,9,12–15,20,42,43 As with studies in female athletes, there is a large difference between prospective and retrospective studies. When the results of studies using either point-in-time or prospective measurements (weekly prevalences) are compared with those of this study, the prevalence is found to be similar (11-29%).9,12,14,15,20 Therefore, the prevalence of hip and groin problems in athletes seems to be similar between men and women. However, further high-quality prospective studies in female populations are needed to confirm this trend.

Function, Participants’ Characteristics and Strength

As expected, the HAGOS Sports and Recreation subscale differed between the hip and groin problem and no problems groups as this was part of the criteria to differentiate these groups. Interestingly, all the other scales of the HAGOS questionnaire also differed between the hip and groin problem and no problems groups indicating that all subscales of the HAGOS questionnaire were sensitive to detect hip and groin problems in female athletes of various sports.

The results indicate found no association between hip muscle strength and hip and groin problems nor between participants’ characteristics data and hip and groin problems, in line with other recent investigations in male athletes.15,27,44,45 However, with only 17 cases, it may have been underpowered to detect an association between these variables and hip and groin pain. Furthermore, the current results may be biased by the fact that participants come from sports with different player profiles and the distribution between the two groups was not homogeneous (e.g., there were no basketball players in the hip and groin problems group). It should also be considered that strength tests were performed in a single position using an isometric contraction, for adduction and abduction movements only. The iliopsoas muscle, for example, was not specifically measured, despite seeming to be a major source of pain in female athletes. It would therefore be interesting for future studies in a female population to also include an assessment of hip flexion strength.

Prevalence of Clinical Entities

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is one of the first to categorize the hip and groin problems in a female athlete population using the Doha Agreement classification system. The most frequent entity identified during the clinical examination was iliopsoas-related groin pain. One possible reason for the large difference between the iliopsoas and adductor entity rates (58.8 % vs 11.8%) is that the criterion for the iliopsoas entity is “iliopsoas tenderness, more likely if pain on resisted hip flexion and/or pain on hip flexor stretching.”25 The “more likely” is an ambiguous element, indicating that a simply iliopsoas tenderness could be sufficient to define the entity, which may have led to different interpretations and methodologies by the authors and contributed to a different number of iliopsoas entities in the studies (Table 5).

Several studies have investigated the epidemiology of hip and groin pain in male athletes using the classification system proposed by the Doha Agreement.10,11,20,26,46,47 In contrast to the findings of the present study, where the most common clinical entity in a female population was iliopsoas-related groin pain, the most frequent hip and groin problem in males seem to be adductor-related groin pain. This is further supported by Serner et al.48 who found a predominance of acute adductor injuries in male athletes using a combination of clinical examination, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound. Only one study reported a majority of iliopsoas entities, which were present in 89% of participants.47 This may be due to a less strict classification approach with vague boundaries between pain and tenderness, allowing more entities to be identified, and indeed a median of 3 entities per athlete was reported.47 DeLang et al.20 highlighted the importance of defining this boundary as their study showed that 50% of athletes who did not report hip and groin problems still had tenderness.

These findings also raise the question of the reliability of clinical examination in identifying clinical entities. Heijboer et al.49 showed that the inter-examiner reliability of the Doha agreement classification ranged from slight to substantial. However, given the variability of results in previous studies, a more precise and standardized approach to clinical examination could increase the reliability and accuracy of diagnosis, thereby minimizing the confusion.

In female athletes, only one other study used the Doha Agreement classification system and examined female soccer players, highlighting a majority of adductor-related cases but with an increase in hip flexor cases (iliopsoas- and rectus femoris-related groin pain) compared to male athletes.17 Despite differences in methodology, both studies found a greater number of hip flexor-related problems, indicating their relevance in female athletes with hip and groin pain. More research is needed to confirm this trend.

Strength-Function Correlation

Analysis of a potential association between hip muscle strength and function in the 91 participants in this study showed no significant correlation. To the authors’ knowledge, no other studies have examined this relationship in a female population, but the current results are consistent with a study by Beddows and colleagues15 in a male population that found no clear association between HAGOS symptom severity and hip muscle strength. Again, the heterogeneity of the sample, consisting of athletes from different sports and therefore with diverse backgrounds, may have influenced the results. An analysis of a single sport population and a larger sample would be valuable to obtain more conclusive results.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study has several strengths. First, it focuses on a population of female athletes that is still largely underrepresented in the scientific literature. Therefore, this study provides new insight into the point prevalence of hip and groin problems in this specific population. In addition, it is one of the first to use the clinical entity approach described in the Doha consensus statement in this same population, which also provides new information. Finally, based on previous scientific studies, this study proposes a new approach and definition for the selection of hip and groin problems, including pain reproduction test as a criterion. This approach could be used for future studies in this field.

A major limitation of this study is the small sample size within each sport, which prevented the authors from conducting a detailed statistical analysis by sport. This was due to constraints such as limited availability of participating teams, which led us to evaluate only those athletes who were present at the time of the scheduled interventions. Another limitation relates to the limited time available for on-site data collection, which was a maximum of 15 minutes per participant. To optimize the time, compromises were made by having two examiners instead of one, as inter-examiner reliability was estimated to be acceptable,49 and by collecting participants’ characteristics data by self-report, which may have slightly biased the accuracy of the data.

A further limitation, is that, due to time and financial constraints, no imaging was performed on participants of the hip and groin problems group to confirm the exact location of pain.

CONCLUSION

A pre-season point prevalence of 14.3% for non-time-loss hip and groin problems was documented during preseason in elite female athletes, which is similar to that previously reported in male athletes. This study is one of the first to use the clinical entity approach in a population of female athletes highlighting that most hip and groin problems appear to be iliopsoas-related followed by adductor-related and inguinal- and pubic-related. This contrasts with findings in males where adductor-related entities predominate.

While as expected, the HAGOS scores differed between the groups, hip muscle strength and participants’ characteristics data did not. Furthermore, no association was found between hip muscle strength and HAGOS scores. This study provides valuable information allowing a better understanding of hip and groin problems in female athletes. More research should be conducted in this population to confirm these findings and to further increase knowledge in this topic.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the players and staff members of the different teams involved in the study for their dedication during the study.