INTRODUCTION

Shoulder pain related to pathology of the long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) can be debilitating. The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) is a known pain generator of the shoulder and can interfere with an individual’s activity and participation.1–3 Tendinopathy of the LHBT may start as an inflammatory condition or tenosynovitis1–3 and may progress to a degenerative tendinopathy (characterized by tendon thickening, disorganization, and irregularity of the tissue including the presence of hemorrhagic adhesions and scarring).3 The overall incidence of LHBT tendinopathy remains uncertain due to its presence as a secondary shoulder condition associated with other shoulder pathology including rotator cuff disease and subacromial impingement.1,4 Overall, there remains a paucity of literature regarding diagnosis, and appropriate management of disorders related to the LHBT, including physical therapy (PT) management and surgical intervention.1,4–6

There is little consensus regarding the optimal approach to treating chronic anterior shoulder pain due to the LHBT tendinopathy.2,3 Conservative management including PT, activity modification, NSAIDS, and steroid injections in the biceps sheath are often recommended prior to more invasive interventions.3,7–9 However, conservative management may be suboptimal and provide only partial/temporary relief of symptoms and many individuals go on to seek more invasive surgical procedures including biceps tendon reattachment (tenodesis) or release (tenotomy).1,10

Physical therapy management of anterior shoulder pain (including LHBT tendinopathy) may involve a multimodal approach addressing impairments of the shoulder, scapular region and cervicothoracic spine. Further, interventions may include therapeutic exercise, joint and soft tissue mobilization as well as retraining of dysfunctional movement patterns.3 Information on the management of subacromial shoulder pain is robust,11–14 however, there remains a lack of high-quality literature describing PT management of individuals with LHBT tendinopathy in isolation.15–20 Most randomized controlled trials exploring PT management for LHBT pain involve the utilization of biophysical agents (ultrasound, electrotherapy, extracorporeal shockwave therapy and iontophoresis) and are of questionable study quality.12,15–20 Invasive surgical intervention is one approach to managing chronic biceps tendinopathy pain, therefore, to potentially avoid such procedures it is essential for physical therapists to recognize other interventions that may be effective in treating LHBT tendinopathy.21 A retrospective chart review is a first step in determining the typical PT interventions utilized in this population to support next steps, which may include the development of randomized intervention trials. The purpose of this retrospective chart review was to investigate the use of PT prior to biceps tenodesis and tenotomy surgeries by assessing the number of visits and use of different interventions and whether they were active or passive. A secondary objective was to report on the themes of PT interventions used in treatment.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective observational cohort study of patients who underwent biceps tenodesis or tenotomy for biceps tendinopathy in a large healthcare system from March 15, 2016, through March 15, 2020, with presurgical physical therapy utilization (active and passive billing codes) extracted for each individual up to 24 months prior to surgery. To guide study reporting, the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD)22 statement was utilized, an extension of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.23

Data Source

Data were extracted from electronic medical records of the UC Health University of Colorado Hospital system. These data include person-level data for all outpatient physical therapy visits. They also included information about physical therapy procedures and subsequent biceps tenodesis or tenotomy surgery.

Data Collection Procedures

This retrospective medical chart review study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (Protocol 20-2235) and the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Newcastle (H-2021-0009).

Eligibility Criteria

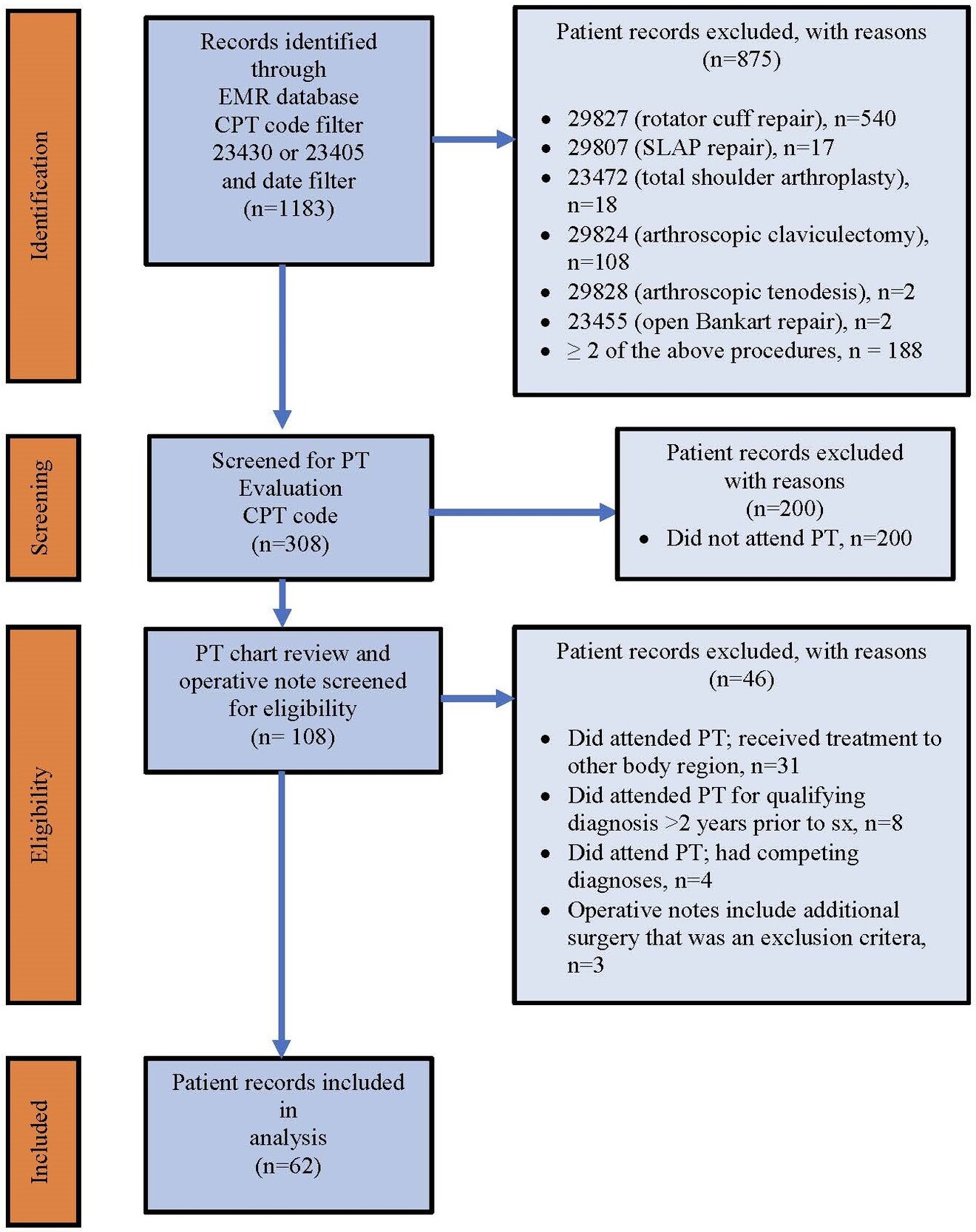

The medical records of eligible patients between the ages of 18 and 85 years of age who underwent biceps tenotomy or tenodesis surgery at the UC Health University of Colorado Hospital between March 15, 2016, and March 15, 2020 were included in the cohort. The study cohort was identified using current procedural terminology (CPT) codes most used for biceps tenodesis (23430) and biceps tenotomy (23405) within a four-year period while excluding patients who underwent concomitant procedures such as rotator cuff repair (29827), distal clavicle excision (29824), and labral repair (23455 and 29807). Arthroscopic biceps tenodesis (29828) was also excluded since this surgery is typically performed in conjunction with another surgery listed above. Subacromial decompression (29826) was not excluded since it is presumed not to interfere with the outcomes of biceps tenodesis or tenotomy. Patients who saw a physical therapist within two years prior to surgery for shoulder pain related to LHBT tendinopathy were included in the analysis. Data were initially filtered by an orthopedic research administrative staff by surgical CPT codes to track which patients had the surgery of interest (23430 and 23405) and dates of surgery to determine preliminary eligibility and determine patients who had the surgery of interest without other associated surgeries. March 15, 2020, served as the cut-off date as all ambulatory services and elective surgeries in the hospital system were significantly impacted by the COVID pandemic after this time period.

Two investigators (AM, PH) completed the next phase of detailed chart reviews on all patient records meeting inclusion criteria based on filtering of CPT codes and dates. Individual charts were reviewed to verify further inclusion based on rehabilitation billing codes, operative reports and rehabilitation notes.

Billing Code Data

Billing code data were initially used to screen which patients had the surgery of interest (23430 and 23405). Following the screening of surgery codes, CPT codes for rehabilitation informed the research team to which patients engaged with physical therapy prior to surgery (within two years of surgery). The use of PT prior to surgery was of interest including the number of individual rehabilitation visits. To satisfy the criteria for physical therapy utilization, patients needed to have at least one PT evaluation (97161-97163) specifically for a shoulder diagnosis (on the same side as the operative side) within 24 months years prior to surgery. All rehabilitation visits based on physical therapy procedure codes were also identified (Table 1). The research team did not record or analyze codes related to PT evaluation or assessment of the patient as the research question involved active and passive intervention codes.

Qualitative Patient Data

Data obtained from general chart review included patients’ age, sex, procedural side (right or left) and baselines scores for patient reported outcome measures including the numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) and The Shortened Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Questionnaire (QuickDASH). Surgical data collected included procedure(s) performed, date of surgery, and relevant perioperative and operative notes. Chart review of the treating physical therapists’ notes included date of PT episode relative to the surgery date, PT problem list (to determine if the patient had anterior shoulder pain vs low back pain or other complaints), shoulder physical examination findings (pain localization, palpation, range of motion, Speeds and Yergason’s tests), and all PT notes in the episode of care (to document specific interventions related to the active and passive codes). Information from PT chart notes included examination and all follow-up treatments which were recorded. Data were extracted using a data collection template created in an excel spreadsheet.

DATA ANALYSIS

The aim of the data analysis was to describe the frequency of patients who attended PT prior to surgery, therefore, the total number of visits patients attended physical therapy was calculated. A secondary aim was to describe the PT interventions received. Active and passive procedure codes were identified from chart review. Active procedure codes were procedure codes used when the patient is actively participating as a component of the PT intervention; these included therapeutic exercise, therapeutic activity, neuromuscular re-education and self-care home management. Passive procedure codes are codes used when the patient is passively receiving an intervention void of patient participation; these included manual therapy, therapeutic modalities, dry needling and other. The percentage of active and passive codes were calculated. Further, thematic analysis of the interventions within each code, based on chart review of rehabilitation notes, was performed for both active and passive procedure codes. Two investigators individually categorized them to organize the qualitative, intervention data into themes. The two investigators (AM, PH) then came together to reach a consensus. Inconsistencies between the reviewers were resolved by discussion, and, if needed, a third reviewer was consulted (SS). The types of interventions performed within each theme were tabulated. Due to the heterogeneous nature of the physical therapy interventions, a quantitative analysis of PT interventions was not feasible.

RESULTS

Of 308 eligible patients who underwent biceps tenodesis or tenotomy surgery 79.9% (246/308) of the total cohort did not receive PT prior to surgery; 20.1% (62/308) patients attended PT for LHBT pain within two years of surgery, and met the inclusion criteria for further analysis (Figure 1). Demographics of the cohort are described in (Table 2). The 62 patients who attended physical therapy had a total of 355 visits for their reported shoulder pain. Of the 62 patients who initiated physical therapy, 11.3% (7/61) received no additional care beyond the initial evaluation. The median number of PT visits for patients was four (IQR=3.5), 22 patients had three visits or less and 64.5% (40/62) participants had four or more visits of PT (Figure 2). After tabulation of active and passive procedure codes, 54.5% (533/978) of the codes were active and 45.5% (445/978) of the codes were passive. There was high utilization of the active codes for therapeutic exercise and activity [96.4% (514/533)] and the passive procedure code of manual therapy [84.3% (375/445)]. Among the remaining 3.6% (19/445) of active codes, interventions included neuromuscular re-education [2.3% (12/533)] and self-care home management [1.3% (7/533)]. Among the remaining 15.7% (70/445) of passive codes, interventions included therapeutic modalities [10.6% (47/445)], dry needling [3.4% (15/445)] to the shoulder region, and other [1.8% (8/445)] (Figure 3).

Theme and coding synthesis of the chart notes within the active code of therapeutic exercise, revealed themes of resistance exercise/muscle performance (subthemes: tendon loading techniques and progressive resistance exercise) and muscle length/mobility (subthemes: stretching and flexibility and range of motion). Theme and coding synthesis of the chart notes within the active code of therapeutic activity included the theme of functional activity. The active code of neuromuscular re-education revealed the theme of motor control training (subthemes: stabilization and muscle re-education). The active code of self-care home management revealed the theme of motor control training (subthemes: stabilization and muscle re-education). Interventions specific to identified themes and subthemes of chart notes based on active codes can be found in Table 3.

Theme and coding synthesis of the chart notes within the passive code of manual therapy included themes of joint mobility (subthemes: non-thrust manipulation and thrust manipulation), soft tissue mobilization (subthemes: general techniques and specific techniques) to the shoulder region and LHBT and range of motion (subthemes: passive range of motion and active assisted range of motion). Among the other passive codes, theme analysis of chart notes included the use of biophysical agents which was the theme for the following billing codes (electrical stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, iontophoresis, ultrasound/phonophoresis, and hot/cold therapy) typically applied to the shoulder region and/or LHBT. Synthesis of chart notes within the passive code of dry needling revealed the themes of dry needling without electrical stimulation and with electrical stimulation to LHBT, glenohumeral and scapular muscles in the shoulder region. Additional themes, subthemes and interventions derived from chart notes of passive codes can be found in Table 4.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this retrospective review was to report on the use of PT for the treatment of LHBT tendinopathy by describing the number of visits and the use of active and passive interventions as defined by procedure codes. A secondary objective was to report on the interventions utilized as described in the PT chart notes. The results indicate overall low utilization of PT prior to surgery for individuals with LHBT (62 patients over four years in a large hospital system). Treating therapists utilized active interventions slightly more than passive interventions, as defined by the procedural codes they selected. The most common interventions were therapeutic exercise (progressive resistance exercise, tendon loading techniques and stretching) and manual therapy (joint mobility, soft tissue mobilization and range of motion), suggesting that a multi modal approach is being utilized. However, there is a lack of evidence for the treatment of LHBT tendinopathy in isolation, therefore these findings provide a first step in understanding how physical therapists manage patients with LHBT tendinopathy.

The following sections aim to better explain these findings, interpret the findings in the context of PT care for shoulder pain including LHBT tendinopathy, and highlight clinical implications, limitations and future directions for research.

Physical Therapy Utilization and Visits

Of patient records meeting eligibility criteria, only 20.1% of patients attended PT for LHBT pain within two years prior to biceps tenodesis or tenotomy surgery. Similarly, in a study of patients who had arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, only 21% of patients received some form of PT in the year prior to their surgery24 which is consistent with the current results. The combined results of the current medical records review and the study by Malik et al.24 are surprising, given contemporary evidence has shown PT is effective for the management of shoulder pain.11,12 Patients may lack knowledge of the benefits of PT for shoulder pain, patients may have barriers to attending PT or may not want to attend due to unknown reasons. According to a recent article on patient expectations, one factor that may affect patients seeking PT care may be that patients lack understanding of PT care including the role of PT.25 Further, patients may not be referred for PT by their general practitioner or specialist, or patients may have had prior PT for LHBT with limited success. In addition, LHBT tendinopathy is difficult to diagnose3,7,26 which may further complicate management pathways.

The median number of PT visits for participants was four (IQR=3.5), and 40 (64.5%) patients had four or more visits to PT. In a study of Medicare beneficiaries with just under 2000 episodes of care for low back, shoulder, or knee pain, patients attended PT for 6.8 visits (SD=4.7) on average over a median of 27 days.27 The results of this medical records review demonstrated a lower number of visits per patient for LHBT which may relate to 1) access issues in a large hospital-based system, 2) other patient-specific reasons stated above, 3) patients in the sample are active and younger (mean age was 43 years +/-13.7), 4) patients may feel equipped to manage their care independently through a home program or other avenues.

Procedure Codes and Intervention Themes

The results of this review demonstrate high utilization of active interventions (54.5% of procedure codes) with therapeutic exercise and activity (96.4%) being the most utilized intervention codes. Therapeutic exercise are activities that include specific muscles at specific joints while therapeutic activities are dynamic activities used to increase functional performance. A recent update of systematic reviews made a strong recommendation for “exercise therapy” as the first-line treatment to improve pain, mobility, and function in patients with subacromial pain syndrome (SAPS),11 however, it is difficult to determine if these recommendations extend to managing pain specific to LHBT tendinopathy. These conditions of the shoulder have some symptoms in common, and in some patients present concurrently. Therefore exercise-based interventions recommended for patients with SAPS such as strengthening, flexibility, and range of motion may also have benefits for LHBT pathology. Intervention themes related to therapeutic exercise included resistance exercise/muscle performance, progressive resistance exercise, and stretching. Several interventions were utilized in the exercise subtheme of tendon loading techniques such as heavy slow load activities which are well supported in the literature for the treatment of tendinopathy28,29 therefore, therapists may be practicing in alignment with guidelines for managing tendinopathies. The main interventions related to the procedural code of therapeutic activity were functional activities (such as reaching, lifting, occupation, and sport-specific activities). Overall, utilization of therapeutic exercise and activity by the clinicians who treated this sample, is in alignment with current recommendations for SAPS.11,12,30

Passive interventions represented 45.5% of the procedure codes, with high utilization of manual therapy (86.2%) among the passive codes. In an update of systematic reviews specific to patients with shoulder pain, manual therapy (joint mobilization and manipulation, soft tissue techniques, neurodynamic mobilizations, and mobilizations with movement) was an intervention with a strong recommendation especially when combined with exercise.11 Manual therapy interventions utilized by PTs in this medical chart review, included soft tissue mobilization, non-thrust and thrust manipulation of the glenohumeral joint, thoracic spine, and cervical spine which are consistent with contemporary evidence for managing SAPS.11,12,31 While it is encouraging that PT interventions were consistent with contemporary evidence for the treatment for shoulder pain, it is unknown if these evidence-based recommendations are applicable to LHBT tendinopathy. A recent Delphi study on PT interventions for treating individuals with LHBT tendinopathy included the following themes within the manual therapy recommendation: soft tissue mobilization (including deep transverse friction and trigger point release), and thrust and non-thrust manipulation to the glenohumeral joint, thoracic spine and cervical spine32 which do align with the findings of this medical records review. Additional Delphi study recommendations included the use of a multimodal approach including exercise combined with manual therapy which again, is consistent with our current findings.32

Among the 20% of passive codes in the current study not attributed manual therapy, interventions included therapeutic modalities (10.5%) and dry needling (3.4%) to the shoulder region and LHBT. Several studies have investigated the use of therapeutic modalities to treat pain specific to the LHBT including iontophoresis, ultrasound, low level laser, and extracorporeal shock wave therapy, with reported improvements in pain or function.15,18–20 A case series of ten individuals with LHBT tendinopathy reported reduced pain and disability and avoided surgery after dry needling, stretching and tendon loading techniques.21 Passive interventions utilizing therapeutic modalities including iontophoresis, electrical stimulation and ultrasound therefore appear to be consistent with available evidence.

Limitations

A limitation to this study was that we were unable to identify patients with LHBT tendinopathy who did not have biceps tenodesis or tenotomy surgery. We did not use the ICD-10 diagnosis codes M75.21 and M75.22 for bicipital tendinitis of the right and left shoulder respectively, because in the medical records system analyzed in this study, diagnoses of the shoulder are often coded more broadly using the ICD-10 code for shoulder pain M25.51. There are a number of reasons clinicians may use this code, one of which is that LHBT pathology often accompanies other primary shoulder pathologies and LHBT is difficult to definitively diagnose2 and may not be diagnosed at an initial visit. However, this makes it difficult to track patients with a specific diagnosis in electronic medical records. The only mechanism to track patients with the pathology of interest (LHBT tendinopathy) was to follow them retrospectively from their date of surgery. As a result, another related limitation is the inability to report on patients who went to PT prior to surgery and improved and therefore did not elect to have surgery. Again, the use of ICD-10 codes that are more general such as “shoulder pain” creates a barrier to identifying patients with a specific diagnosis. This retrospective chart review would have been more comprehensive if LHBT tendinopathy was more explicitly diagnosed; this would have afforded us the ability to track patients who went through a course of PT regardless of whether they had surgery. We are therefore unable to determine if the number of visits and PT-based interventions provided would have been different for those who did not have surgery and we are unable to determine if our studied sample is more inclusive of those who “failed” conservative management. Further, it is possible that patients excluded from our sample received physical therapy care outside of the healthcare system which is challenging to track due to a lack of documentation including billing codes.

Clinical Implications

Physical therapy is underutilized prior to biceps tendon surgeries and few guidelines exist to guide clinical care for LHBT tendinopathy. Guidelines exist for the management of SAPS and for tendinopathy, including tendinopathies of the rotator cuff, which may serve as a guide due to the paucity of recommendations specific to LHBT tendinopathy. Based on this review, when PT was utilized, active interventions were utilized more often than passive interventions, and the common themes from clinician records of exercise, manual therapy, and therapeutic modalities were all consistent with evidence-based recommended interventions used to treat SAPS and tendinopathy. Further research in the form of randomized controlled trials is needed to determine if these intervention approaches provide optimal effective care for patients with LHBT tendinopathy.

CONCLUSION

Physical therapy was not commonly utilized prior to undergoing biceps tenodesis and tenotomy surgery by patients seeking care in a large hospital-based health system. Further research is needed to understand the reasons for poor utilization and whether the PT interventions commonly utilized provide optimal care for patients with LHBT tendinopathy.

Conflicts of interest

All authors do not have conflicts of interest to report.

Grant Support

This work was supported by The American Academy of Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapists (AAOMPT) under a grant from Cardon Rehabilitation (Ontario, Canada). Neither AAOMPT nor the funding agency had any role in the study design, analysis, interpretation, or decisions about publication.