Introduction

The integration of musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSKUS) into clinical practice has significantly transformed the diagnostic landscape for rehabilitation providers, offering a detailed, real-time view of musculoskeletal structures in a cost-effective and non-invasive manner. This modality is especially beneficial for conditions like ischiofemoral impingement (IFI), a condition characterized by the narrowing of the ischiofemoral space (IFS), which lies between the ischial tuberosity and the lesser trochanter of the femur. Narrowing of this space can lead to compression of adjacent soft tissue structures, most notably the quadratus femoris muscle, resulting in posterior hip pain that often radiates down the leg.

IFI may result from congenital abnormalities, acquired anatomical changes, or post-surgical complications such as hip arthroplasty. It is often underdiagnosed due to its subtle presentation and overlapping symptoms with other hip pathologies, such as hamstring tendinopathy or piriformis syndrome. When it is diagnosed correctly it is commonly based on reproduction of the known pain patterns during movement that lead to a further shrinking of the already reduced IFS. These movement patterns include long stride-walking,1 the flexion-abduction-external rotation (FABER) test,2 or during motions of extension-adduction-external rotation known as the posterior impingement test.3 Traditionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been the gold standard for diagnosing IFI, offering detailed visualization of the IFS and associated pathologies. However, MSKUS has gained increasing recognition for its utility in musculoskeletal imaging, providing several advantages over MRI, including portability, dynamic real-time imaging, and the absence of ionizing radiation.

This article explores the application of MSKUS for evaluating the IFS in patients with suspected IFI, emphasizing its potential role in early diagnosis, accurate management, and tailored therapeutic interventions for rehabilitation specialists. By using MSKUS, clinicians can enhance diagnostic accuracy and improve patient outcomes by facilitating timely and targeted treatment strategies.

Epidemiology

Hip disorders are prevalent, affecting about a third of adults aged 38 to 77, with higher rates observed in older adults, especially women. IFI specifically is more common in females and often occurs bilaterally.4,5 Although the precise prevalence of IFI syndrome (IIS) is unknown, it is frequently overlooked as a potential cause of hip pain.

Anatomy of the Ischiofemoral Space

The ischiofemoral space (IFS) is the anatomical interval between the lateral cortex of the ischial tuberosity and the medial cortex of the lesser trochanter of the femur. Within this space lies the quadratus femoris muscle, along with the sciatic nerve and associated vascular structures, all of which are crucial to hip function. Narrowing of the IFS, typically defined as a distance below 1.5 cm, can lead to IFI, a condition characterized by pain and restricted motion in the posterior hip. In addition to the IFS, the quadratus femoris space (QFS)the distance between the hamstring origin on the ischial tuberosity and the insertion of the quadratus femoris muscle—is another critical measurement in assessing IFI.

When the IFS becomes narrowed, compression of the quadratus femoris muscle and the sciatic nerve can occur, leading to the hallmark symptoms of IFI, including deep posterior hip pain and potential nerve-related symptoms. Normal IFS values range from 2 to 2.5 cm, and accurate measurement of this space is crucial for diagnosis. Given that the actual space is highly variable based on the gait cycle or what position the hip is in during testing, and MRI tends to overestimate the measurement,6 MSKUS is the perfect tool for assessing this space either statically or dynamically. Dynamic hip MSKUS can corroborate IFI and space with the change in position of the lower extremity, as well as to assess whether the symptoms are due to other potential causes.7 MSKUS is an invaluable tool for visualizing these structures, offering dynamic, real-time imaging that enhances diagnostic accuracy in cases of suspected IFI .

Pathophysiology of Ischiofemoral Impingement

IFI is thought to result from repetitive mechanical compression of the quadratus femoris muscle as the femur moves into extension and external rotation, which decreases the IFS. Over time, this chronic impingement can lead to muscle edema, atrophy, and in severe cases, tendinosis or tearing of the quadratus femoris muscle. Patients typically present with vague posterior hip pain that is exacerbated by hip extension or external rotation, making clinical diagnosis challenging due to symptom overlapping with other posterior hip pathologies.

An important anatomical factor influencing the IFS is the femoral neck anteversion angle, which refers to the angle between the femoral neck and the shaft of the femur. Individuals with excessive femoral anteversion (a larger angle) are at an increased risk for IFI, as this greater angle shifts the lesser trochanter posteriorly, further restricting the already limited space. This anatomical variation, coupled with the repetitive mechanical stress on the quadratus femoris, exacerbates the impingement and contributes to the clinical presentation of IFI.8

Given the non-specific nature of the symptoms and the complexity of posterior hip pain, imaging techniques such as MSKUS are crucial for accurately diagnosing IFI and differentiating it from other hip pathologies, thereby preventing misdiagnosis and guiding appropriate treatment interventions.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing IIS is challenging since its symptoms can mimic those of other conditions affecting the lower back, sacroiliac joint, or sciatic nerve. A thorough physical examination can aid in identifying potential cases. Two common physical tests include:

-

Long-stride walking test9,10: The patient is asked to walk with long strides while holding the affected buttock. Pain during this activity suggests IIS, especially if it resolves with shorter strides.

-

Ischiofemoral impingement test11–13: With the patient lying on their side, the examiner applies pressure to the buttock near the ischium while passively extending the hip. Pain in neutral or adducted positions—but not in abduction—indicates the likelihood of IIS.

Imaging studies are essential for confirming IIS. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) remains the gold standard, as it provides accurate measurements of the ischiofemoral space and can detect abnormalities in the quadratus femoris muscle.14

Musculoskeletal Ultrasound (MSK US) in Evaluating the Ischiofemoral Space

While MRI has traditionally been the primary diagnostic tool for IIS, MSKUS is gaining recognition as a viable, radiation-free alternative. MSKUS offers real-time, dynamic visualization of soft tissues and bony structures in the posterior hip, making it a valuable tool for assessing the anatomy involved in IIS, including the IFS and quadratus femoris muscle.

MSKUS uses high-frequency transducers to provide detailed imaging of muscles, tendons, and spaces, allowing for a dynamic assessment of the ischiofemoral and QFSs during hip movement. This ability to visualize soft tissues in real time makes MSKUS particularly useful in diagnosing conditions like IFI, where the impingement is influenced by changes in hip position.

Protocol for MSK Ultrasound of the IFS

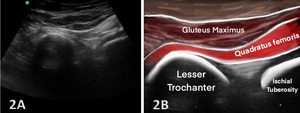

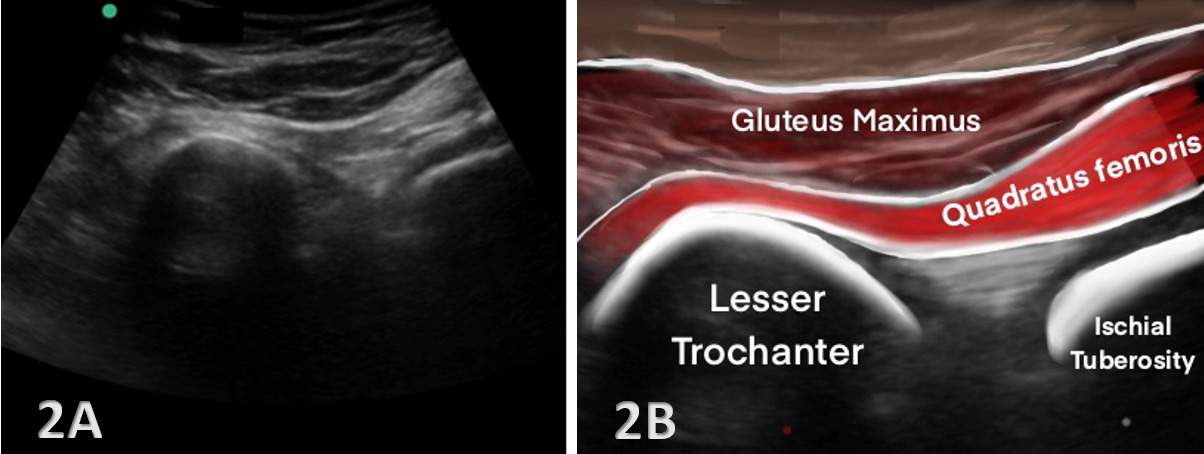

To ensure consistent and accurate evaluation of the IFS and surrounding structures, a standardized scanning protocol should be followed. Typically, the patient is positioned either in a prone or lateral decubitus position, with the hip in neutral or slight extension and external rotation to optimize visualization of the ischiofemoral region.

-

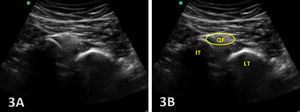

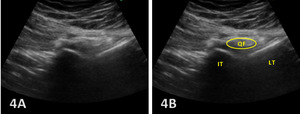

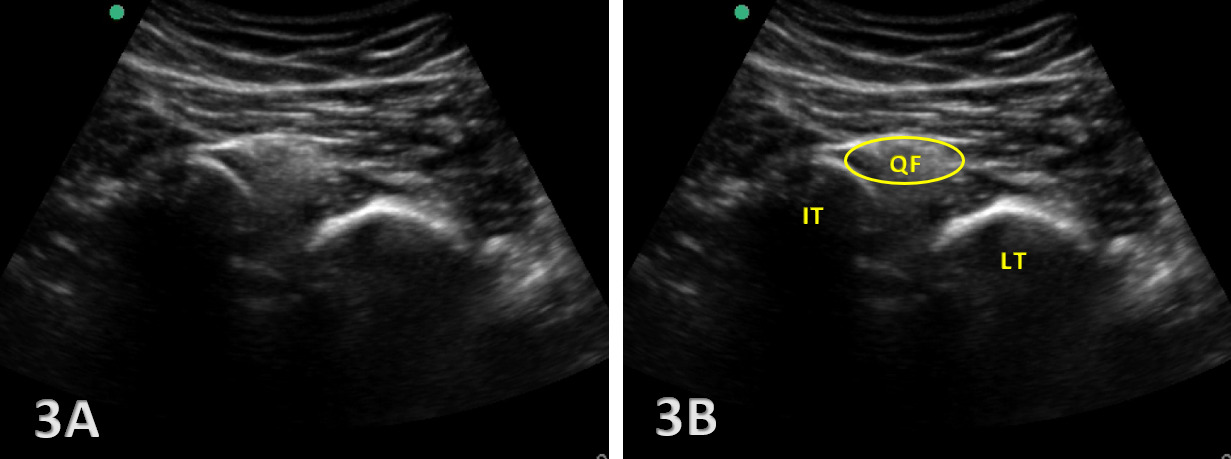

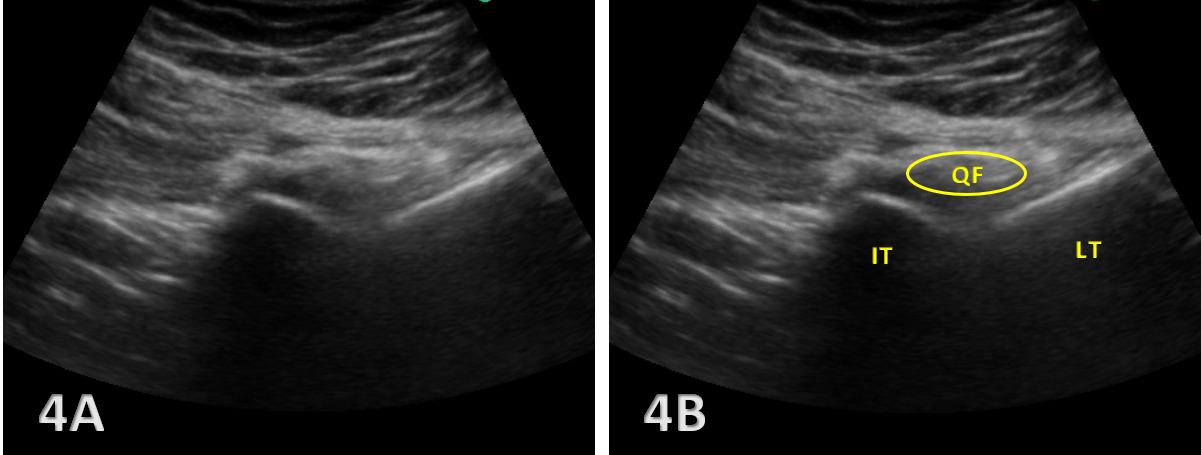

Transverse View: The ultrasound transducer is placed transversely across the gluteal region, oriented to visualize both the ischial tuberosity and the lesser trochanter. This view allows for direct measurement of the IFS and identification of the quadratus femoris muscle.

-

Longitudinal View: The probe is also oriented along the long axis of the quadratus femoris muscle to evaluate for signs of edema, atrophy, or tendinopathy within the muscle, which are commonly associated with IFI.

By adhering to these protocols, MSKUS provides a detailed and dynamic evaluation of the IFS, enabling clinicians to assess anatomical variations and soft tissue changes that contribute to IFI, thereby improving diagnostic accuracy and guiding treatment decisions.

Key Findings - Visualization of Ischiofemoral Space

MSKUS plays a pivotal role in identifying key diagnostic features of IFI by providing detailed imaging of the deep external rotator muscles and associated structures. Several hallmark findings can be observed with ultrasound:

-

Narrowing of the IFS: A key indicator of IFI is the decreased distance between the ischial tuberosity and the lesser trochanter. Ultrasound allows for precise measurement of the IFS, particularly at the point of greatest narrowing, which is critical for diagnosing impingement. IFS measurements by MSKUS have been shown to be very similar to those obtained with MRI.15

-

Quadratus Femoris Edema or Atrophy: MSKUS can identify increased echogenicity in the quadratus femoris muscle, which suggests edema or early degeneration. This muscle is most involved in IFI and serves as a crucial diagnostic marker.

-

Dynamic Testing: One of the strengths of MSKUS is its ability to assess the IFS during hip movement, such as extension and external rotation. This real-time imaging allows clinicians to directly observe impingement of the quadratus femoris during dynamic motion, further aiding in diagnosis.

In addition to these findings, MSKUS provides detailed visualization of the deep external rotator muscles, which are critical in the context of IFI:

-

Quadratus Femoris: The primary muscle involved in IFI, located between the ischial tuberosity and the lesser trochanter.

-

Obturator Externus: Situated beneath the quadratus femoris and often affected in cases of IFI.

-

Piriformis, Superior Gemellus, and Inferior Gemellus: Alongside the quadratus femoris and obturator externus, these muscles form the deep external rotators of the hip and are located near the sciatic nerve, making them relevant in differential diagnosis.

-

Hamstring Muscles: Although not external rotators, the proximity of their attachment to the ischial tuberosity can complicate the distinction between hamstring pathologies and IFI.

By enabling detailed imaging and dynamic assessment, MSKUS enhances the clinician’s ability to accurately diagnose IFI and differentiate it from other posterior hip pathologies, particularly those affecting the deep rotator and hamstring muscles.

Clinical Relevance for Rehabilitation Providers

For rehabilitation providers, incorporating MSKUS into clinical practice offers several benefits:

-

Early Diagnosis and Prevention: Early identification of IFS narrowing and quadratus femoris pathology allows for prompt intervention with conservative measures such as physical therapy, activity modification, or injection therapies.

-

Non-Invasive Diagnostic Tool: MSKUS is a non-invasive, patient-friendly imaging modality that can be used in the outpatient setting, providing real-time feedback without the need for advanced imaging centers.

-

Guidance for Treatment: MSKUS can guide therapeutic interventions, such as percutaneous quadratus femoris injections or physical therapy designed to modify movement patterns that exacerbate IFI.

Conclusion

MSKUS is a highly practical and effective tool for evaluating the IFS in patients presenting with posterior hip pain. Its ability to provide high-resolution, dynamic imaging of soft tissue structures makes it an invaluable adjunct to clinical examination, significantly enhancing diagnostic accuracy. MSKUS allows for a detailed assessment of the IFS, visualization of deep gluteal muscles, and evaluation of sciatic nerve dynamics, making it particularly useful in diagnosing IFI, a condition often overlooked due to its subtle presentation.

For rehabilitation providers, including physical therapists, physiatrists, and orthopedic specialists, the integration of MSKUS into the diagnostic process enables earlier detection and more targeted treatment of IFI, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes. Its radiation-free nature and capacity for real-time dynamic assessment further establish MSKUS as a promising, essential tool in the management of posterior hip pathologies.