INTRODUCTION

Ankle sprains are one of the most common orthopedic injuries that occur in the general population and among athletes.1,2 Injuries to the lateral ankle complex are the most common type of ankle sprains.1 Acute lateral ankle sprain injuries are initially treated with conservative treatment including modalities to address pain, swelling, and inflammation. These modalities include ice, rest, and anti-inflammatory medication. In severe cases, immobilization may be necessary. Physical therapy is recommended, focusing on muscle strengthening, balance training, and proprioception. These therapy treatments are essential parts of conservative treatment.3 Despite conservative management, patients may subsequently develop chronic lateral ankle instability (CLAI). In a study by Doherty et al. 40% of the 82 patients included who sustained a first-time acute lateral ankle sprain developed CLAI.4

Freeman et al. described two types of CLAI. Functional instability describes a patient who reports the foot feels unstable or “gives out.”5,6 Mechanical instability occurs when there is pathological laxity of the ankle with increased varus tilt of the talus under inversion stress.5,6 In acute ankle sprains, the anterior talo-fibular ligament (ATFL) is the most commonly injured ligament followed by the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) which occurs in more severe sprains.1,7 Therefore, surgical treatment for patients who fail conservative treatment targets stabilizing the ATFL and occasionally the CFL as well.8 The Brostrom repair was first introduced in 1966 to reapproximate the ATFL.9 Later Gould created a modification which included the extensor retinaculum which was used to augment the Brostrom repair.10

The Internal Brace (IB) was first created as a “fibertape” (suture tape) augmentation for ligament reinforcement to act like an “internal seat belt.” While it was first used in the upper extremity, it was first used for CLAI in 2012. In CLAI there has been clinical endorsement of fibertape augmentation to maintain stability and allow for earlier range of motion and mobilization.11 This variation of the traditional Brostrom procedure has shown promise with improved stability with quicker return to function.11 Biomechanical studies have shown superior strength of the repair at post-op time zero when comparing the Brostrom augmented with fibertape and the Brostrom-Gould repair.12 Clinical studies also support outcomes after using fibertape augmentation over the Brostrom-Gould repair.11,13 Because of the emerging superiority in the literature of fibertape augmentation regarding graft strength and return to function, the authors’ recommend early mobility and more aggressive rehabilitation compared to patients who have undergone a Brostrom or Brostrom-Gould repair.

While surgical technique and the biomechanics of the IB has been studied, no specific rehabilitation protocol exists when IB is used during surgical intervention.14,15 Previous authors have discussed rehabilitation protocols specifically for patients treated with a modified Brostrom; however, the authors recommend earlier mobilization and return to activity with the IB augmentation compared to the protocols created for Brostrom-Gould repairs.14,15 Therefore, the purpose of this clinical commentary is to describe an early mobility and rehabilitation protocol after IB augmentation for the ankle.

PROCEDURE

The ankle IB surgical technique has been thoroughly described in the literature.14,15 Briefly, an ankle arthroscopy to treat intra-articular pathology is performed prior to performing the lateral ankle stabilization with IB augmentation. After the ankle arthroscopy is performed, the lateral ankle incision is performed in a linear fashion across the distal fibula 1 cm from the proximal for the fibula tip in line with the ATFL. Sharp dissection is performed through skin and subcutaneous tissue in layered fashion retracting the anterolateral fat pad. The peroneal tendons are visualized and peroneal pathology is addressed appropriately.

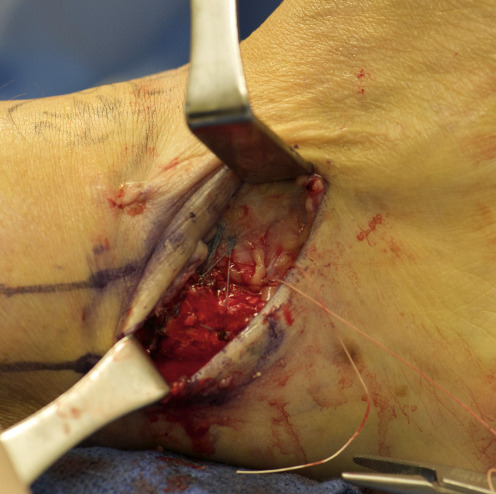

The ATFL is identified and removed from the distal fibula in a cuff of tissue with the inferior extensor retinaculum. In standard fashion, a 4.5mm Swivelock biocomposite suture Anchor (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) is placed into the talar body in a trajectory to avoid violation of the tibiotalar or subtalar joint and the attached sutures are passed through the ATFL and extensor retinaculum cuff (Figure 1). Two 3.5mm BioSuture Tak suture anchors (Arthrex) are implanted into the anterolateral aspect of the distal fibula (Figure 2) and the FiberTape is passed from the articular side to the extra articular side being secured with hand ties. We recommend placing the foot in neutral dorsiflexion and slight eversion for the tying of the sutures for the Brostrom procedure.

The fibertape from the first anchor is passed through the eyelet of the second anchor in the IB augmentation prior to implanting it on the anterolateral aspect of the fibula, with careful attention to avoid penetration of the ankle joint or fracture of the fibula. The anchor is inserted with the ankle in resting plantarflexion position to avoid significant decrease in motion secondary to an over tensioned augmentation (Figure 3). Vicryl is used to repair the sleeve of tissue to the neighboring periosteum (Figure 4). Non-absorbable suture is recommended for the skin followed by a posterior splint application.14

POST–OPERATIVE REHABILITATION

Post–operative management of patients who undergo IB augmentation of Brostrom lateral ankle instability is outlined in Table 1. These guidelines are modified for each patient based on post–operative exam and radiographic findings. The current program, spanning 12 weeks, utilizes early mobilization with no casting to improve return to sport time and reduce complications from stiffness. Wound healing should be evaluated at every exam. There should be open communication between the surgeon and physical therapist if there are any concerns of wound dehiscence, infection, or other post– operative complications. If any signs of wound dehiscence exist, it may be necessary to decellerate rehabilitation and weight bearing status until the wound is adequately healed. After sutures are removed, the wound should be covered and well-padded in the brace or boot to prevent dehiscence and infection.

REHABILITATION PROGRAM SUMMARY

Table 1 presents treatment goals, weight bearing status, and physical therapy rehabilitation interventions after IB augmentation. Initially, patients are immobilized in a non-weight bearing splint immediately after surgery for 3-5 days and utilize the appropriate assistive device. The patient is then allowed to progress into full weight bearing in a CAM boot after day 3-5, assuming the wound is healing without complications. As early as three weeks postoperatively, the patient may transition into an ASO brace and a supportive tennis shoe dependent on the patient’s progress in physical therapy and wound evaluation. Inversion exercises are restricted until week six to not stress the lateral ankle repair. Patients may be able to return to sport as early as 8-10 weeks after surgery, although this protocol outlines interventions through 12 weeks post-op.

DISCUSSION

Controversy regarding immobilization and early mobilization after lateral ankle stabilization has been discussed in the literature. Petrera et al. analyzed patients who underwent a modified Brostrom with two double-loaded suture anchors and early mobilization. They concluded that this construct allowed for immediate weight-bearing with a low failure rate and improved patient functional outcomes. Vopat et al. compared studies examining early and delayed mobilization after primary lateral ankle ligament stabilization.16 They found early mobilization had improved functional outcomes; however, patients demonstrated increased objective laxity and higher complication rates.15 Of note, both of these authors excluded patients who underwent IB fixation and therefore comparisons and conclusions regarding outcomes after augmention with the IB cannot be made.

Schuh et al. performed a biomechanical study comparing the Brostrom technique to suture anchor repair and to IB augmentation.12 They found the Brostrom alone and the suture anchor group failed at a 24.1 degree rotary displacement angle, while the IB group failed at 46.9 degrees (p=0.02). They also found that the IB group had a larger torque at failure of 11.2 Nm compared to 8.0 Nm for suture anchor group and 5.7 Nm for the Brostrom alone group. They concluded that the IB group had significantly superior performance in regards to angle at failure as well as failure torque.12 These findings suggest that the IB augmentation can support early weight-bearing and return to activity compared to what has previously been described in the literature for a modified Brostrom.

Improved strength and functional outcomes have been described with IB augmentation over traditional Brostrom or Brostrom-Gould repair.11–14 Therefore, the authors’ believe that early mobilization and progressive therapy is indicated given the strength of the IB augmentation. Specifically, Jain et al. compared 148 patients who underwent either a Modified Brostom-Gould repair versus IB augmentation. They found IB augmentation had better outcomes of early rehabilitation, earlier return to pre-injury activity, and better functional outcomes and VAS scores.11 Flaherty et al. performed a similar study comparing the Modified Brostrom-Gould versus IB augmentation. They found those who underwent surgery with IB augmentation had better overall function and fewer complications with lower recurrence of pain and quicker return to walking than those who underwent the Modified Brostrom.13 Finally, Kulwin et al. performed a randomized control trial of 119 patients who either received a modified Brostrom procedure alone or the modified Brostrom with suture tape augmentation. They used an accelerated rehabilitation protocol similar to what is described in the current paper. They found an average return to preinjury level of activity to be achieved at 17.5 weeks after modified Brostrom repair versus 13.3 weeks after suture tape augmentation. Only one patient in the suture tape group was unable to complete the accelerated rehabilitation protocol while four in the modified Brostrom group failed to complete the protocol.15

Conclusion

IB is still a novel surgical approach without established rehabilitation protocols. A well-constructed rehabilitation protocol that leverages the improved biomechanical characteristics of IB technique is necessary. In this commentary the authors present a rehabilitation protocol that describes an appropriate approach for early mobilization with the goal of early return to activity that has proved to be beneficial in returning patients to function in an expedited fashion.