INTRODUCTION

A variety of therapeutic interventions are available to clinicians to improve recovery, ease inflammation, and alleviate pain associated with injury and exercise. Namely, cold and heat therapy, percussive therapy, vibration therapy, and infrared (IR) light therapy are tools used to decrease inflammation, pain, and improve recovery.1–3 However, there has yet to be consensus regarding the most commonly used therapeutic interventions in the professional sphere of rehabilitation and pain management. Establishing a cohesive understanding of how such therapies are used and in what circumstances would allow practitioners to consider the most appropriate procedures to implement in the clinic.

The objective of this Delphi study was to attain consensus regarding the use of therapeutic interventions in clinical settings. The interventions of interest include percussive therapy, vibration, infrared (IR) light therapy, heat, and cryotherapy. For the purposes of this study, “therapeutic interventions” refers to the use of modalities or technologies to improve patient outcomes. Providing clinicians with information regarding consensus on therapeutic interventions use will allow for cohesion in the rehabilitation and performance fields.

METHODS

This study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board (#UP-23-00710). Requests for participation were sent via email and responses were collected via a secure collection system, Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT).

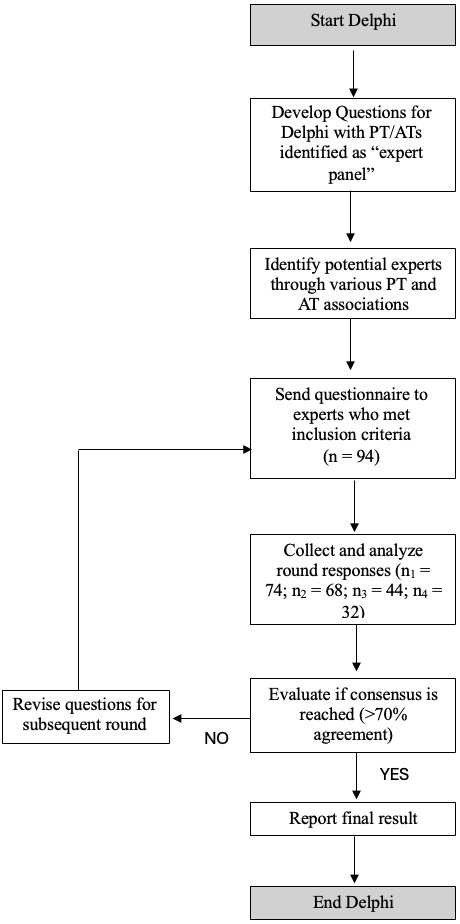

A visual representation of the procedures used in this Delphi study can be found in Figure 1. An expert panel of six Athletic Trainers (ATs) and/or Physical Therapists (PTs) working in collegiate/professional sports or academic settings served to help develop the questions for distribution to the broader population of interest.

An initial recruitment email to participate in the study was sent to individual professionals as well as members of a variety of professional Physical Therapy and Athletic Training associations and societies, including the American Academy of Sports Physical Therapy, American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Therapists, and Professional Baseball Physical Therapy Society. Participants were provided with information about the Delphi methodology, objectives of this study, and a web link to a series of screening questions. To be included in the study, individuals had to be a licensed physical therapist or certified athletic trainer, have worked at least 1,000 hours in the prior five years with athletic populations, and used one or more interventions of interest (i.e., percussive, vibration, heat, cold, and IR light therapy) in the prior five years.

Prior to the questions of each round of surveys, participants agreed to online informed consent. Additionally, definitions of the interventions and conditions of interest were supplied. These are provided in Appendix A. An example of question formatting can be found in Appendix B.

Round 1 of questionnaires asked participants about their use of interventions in specific circumstances including: preparation for physical activity, recovery from physical activity, treatment of acute joint pain, treatment of acute soft tissue/muscle pain, treatment of chronic joint pain, and treatment of chronic soft tissue/muscle pain. The interventions of interest were defined as following:

-

Local heat therapy: The application of heat to a specific area of the body where the skin temperature is heated to 38-43℃ (100.4-109.4ºF) for a defined period of time to elicit physiological and neurological effects for therapeutic benefit.4,5

-

Local Cold (Cryo) Therapy: The application of cold to a specific area of the body where the skin temperature is cooled to 5-13℃ (41-55.4ºF) for a defined period to elicit physiological and neurological effects for therapeutic benefit.6

-

Local Infrared Light Therapy: The exposure of bare skin to a known therapeutic dose (fluence) of infrared energy between 700 and 3000 nm wavelength to elicit physiological and neurological effects for therapeutic benefit.7–9

-

Local Vibration Therapy: The application of vibratory stimuli, at a very low intensity, which causes the tissues to move rapidly in an oscillatory fashion. This has a smaller amplitude and more gentle massage type treatment compared to Percussive Therapy.10–12

-

Percussive Therapy (typically delivered via “massage guns”): Rapid and repetitive application of compressive forces at a set frequency with potential effects larger and longer lasting than local vibration therapy.13

Respondents were asked to classify their frequency of use of the interventions in each condition as: “Never,” “Rarely,” “In Some Instances,” “In Most Instances,” “Always,” or “I have never used this technology.”.

The second round of questionnaires removed the extreme qualifications of “Never” and “Always,” as it appeared that many respondents did not acknowledge the use of the interventions in such definitive terms. The qualification, “I’ve never used this technology” was also removed, as training in all interventions is now commonplace. In addition, the second, third, and fourth round of questions provided participants with an open response to specify what indications or contraindications would either encourage or deter the use of each intervention. This second survey also indicated to which area the intervention would be applied (i.e., when treating acute joint pain, the modality would be applied “directly to the joint”).

Using the commonly cited indications and contraindications from Round 2, the third round of survey questions asked participants to indicate when they would use the intervention of interest in the absence of obvious contraindications (i.e., post-operative wounds, sensory deficits, bruising or open wounds, etc.). Participants were able to identify indications or contraindications in open responses that seemed relevant to the use of the therapeutic intervention.

Many respondents continued to list the contraindications that were excluded by the previous statement as a reason to not use the intervention. The fourth round of surveys emphasized that the answer to each circumstance should omit the consideration of the listed conditions.

Additional information was collected at the end of each survey that lent itself to further sub-analysis. Supplemental details collected included: highest degree obtained, years practiced as an AT or PT, completion of a fellowship and/or residency as a PT, and primary place of work/clinical practice. Survey questions regarding this collection are provided in Appendix C.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using Qualtrics software (Version: March 2024; Provo, UT). Data are represented as quantities and percentages where indicated. A specific threshold of agreement in Delphi studies has not been well established in the literature, with percentages ranging from 50-97%.14 Expert consensus in this study was considered to be reaching a threshold of at least 70% agreement.

Regarding the sub-analyses, the Qualtrics built-in ‘Relate’ feature was employed to examine the relationship between the variables of interest and the selection of the therapeutic intervention. This feature generates a tabular output that cross-references the selection of an intervention with respondent’s selection of personal details (i.e., completion of a fellowship and/or residency).

RESULTS

A total of 94 individuals met the inclusion criteria for participation in this study. Of those contacted 74 completed the first round of the survey. As mentioned earlier, there was no consensus reached after this initial round, as many respondents did not answer extremes (i.e., “Always” and “Never”). A total of 68 individuals participated in the second round. The third round of surveys received 44 completed responses, and lastly, the fourth round of surveys had a total of 32 respondents. Descriptions of the populations of interest are shown in Figure 2. Following the fourth round of surveys, there was no consensus (>70% agreement) reached regarding any of the interventions of interest. Therefore, it was decided that consensus on when participants would consider the use of a therapeutic intervention would be reported. For interpretation, “consideration” was defined as a selection of “In Some Instances” or “In Most Instances.”

From the results outlined, it is clear that physical therapy and athletic training experts would consider using percussive, local vibration, and local heat therapy in the preparation for physical activity; local cryotherapy in recovery from physical activity; local cryotherapy for the treatment of acute joint pain and acute soft tissue/muscle pain; local heat and local cryotherapy for the treatment of chronic joint pain; and percussive, local vibration, local heat, and local cryotherapy in the treatment of chronic soft tissue/muscle pain. It was overwhelmingly agreed that percussive therapies should rarely be used, when applied directly to the joint, in cases of acute joint pain (81.3% consensus in Round 4). However, outside of this agreement, none of the modalities of interest reached the 70% threshold recommending against use.

Consideration, as defined above, for therapeutic interventions use was agreed upon for many interventions. Responses to the third and fourth rounds of survey questions can be found in Appendix D and E, respectfully. A summary of the considerations for each therapeutic intervention corresponding to the conditions of interest in round 4, is displayed in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Local cryotherapy, or cold therapy, is an intervention that has dominated the recovery and pain industries in recent years. Typically delivered in the form of ice or cold-water immersion, cryotherapy is a commonly relied-on practice to alleviate pain associated with injury or exercise-induced soreness.15 It is purported that cold therapy may reduce muscle metabolism, neural sensitivity, and circulation to limit the inflammatory response.16 From this evidence, it is unsurprising that a majority of respondents considered cryotherapy in situations to alleviate pain and inflammation.

Alternatively, heat therapy is a traditional therapeutic intervention that is associated with an increase in blood flow, delivering increased nutrients and oxygen to the damaged tissue, preparing the body for exercise, as well as aiding in the healing process.17 In addition, heat therapy is thought to mediate the transmission of pain through the modulation of heat-sensitive Ca2+ channels.17 Through these mechanisms, thermotherapy has been reported to improve symptoms of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), acute muscular pain, and musculoskeletal disease.4 Given this evidence, it makes sense that respondents considered using this intervention for preparation for physical activity, as well as aiding in situations related to chronic pain.

Percussive therapy, typically delivered via “massage guns,” have become increasingly popular in recent years. This type of treatment has been shown to reduce pain, improve recovery, and assist in preparation for sport through a variety of mechanisms that result from the combination of compression and vibration therapy.3 Percussive therapy is reported to increase blood flow, improve range of motion, aid in myofascial release, and decrease muscle soreness and inflammation.3,18,19 Therefore, it is unsurprising that a majority of respondents noted a consideration for their use in preparation for physical activity and treatment of chronic muscle/soft tissue pain. Consideration for the use of this intervention in recovery from physical activity approached the identified threshold, suggesting it also could be a valuable tool in certain circumstances.

Similar to percussive therapy, vibration therapy, particularly at low frequencies, has a variety of cited benefits that may improve muscle performance and aid in recovery. Namely, low-frequency vibration has been reported to enhance muscle activation, increase neurophysiological signals to muscles, and increase blood flow.20 In addition, vibration therapy may mediate pain by interrupting the pain transduction pathway.21 As such, it seems understandable that the vibratory treatment was considered for use in the context of physical activity preparation as well as treatment of chronic pain of the muscle/soft tissue. Again, this intervention approached the identified threshold in the context of recovering from physical activity, indicating that it may be useful in certain circumstances.

Last, there appears to be renewed interest in the use of IR light therapy for the conditions of interest in this study. IR light therapy is known to improve blood flow, mitigate and repair muscle damage, increase ATP production, and increase muscular excitability.7,8,22 Recent findings suggest that photobiomodulation (PBM), such as is used in IR light therapy, may increase sports performance, as well as aid in acute and chronic pain reduction.22,23 One reason for the lack of consideration for this intervention throughout the study is likely related to the financial and time investment required when using biophysical interventions, such as IR light therapy. A 2023 clinical reasoning statement by Short, Tuttle, and Youngman noted that " the cost of machinery and technology and time required […] has led to changes in ethics statements, physical therapy education, reimbursement, and overall trends of use."24 Therefore, it is likely that respondents either do not have access to such interventions or opt for more cost- and time-effective tools.

The clinical selection of therapeutic interventions for particular conditions appeared to rely heavily on patient presentation. For example, many respondents wrote in the open response that using an intervention “is dependent on many things,” “[is] dependent on individuals, types of injuries, where they are at in rehab,” “[is] based upon patient preferences/beliefs/response to treatment,” and there are “ma[n]y factors to consider.” While the quotes used above represent just a few respondents, the sentiments were continuous throughout all rounds.

Outside of this factor, there were interesting trends that explained differences in therapeutic intervention selection relating to workplace and training. One such analysis investigated the influence of work location on the selection of treatment. Specifically, it was discovered that an overwhelming majority of those who selected their place of work as “sports team facility,” “academic institution,” or “outpatient stand-alone clinic” noted that they would consider using percussive therapy; while those who were “hospital-based” would not. A similar trend arose regarding local IR light therapy with many in sports facilities considering the use of a therapeutic intervention, and a limited number of those in a hospital considering the use. It is important to note, when considering these analyses, that most respondents described their location of work as a “sports team facility.”

There are several reasons for the discrepancies in treatment usage across locations of work. One such reason could be the availability of interventions. In hospital-based and academic settings, the institutions may have compliance and regulations that govern the use of particular interventions. In addition, time constraints may discourage the use of therapeutic interventions in treatment. In outpatient stand-alone clinics, hospital-based settings, gyms, and academic facilities sessions are often time-based, and a particular treatment may not be feasible in the allotted time. Further, the use of the intervention itself may not be billable, and therefore the financial benefit of intervention use may not outweigh the familiarity and feasibility of other interventions that may be reimbursable. Alternatively, in sports team facilities most interventions are likely available, and clinicians are less restricted by schedules or billing regulations. This may further promote the use of an intervention. Lastly, exposure and training to newer therapeutic interventions, such as in academic institutions or through continuing education, may influence their use in particular settings.

Another interesting finding was in the self-selected profession of the respondents. Participants could select between a PT that completed a residency or fellowship, PT that did not complete a residency or fellowship, and AT. Differences in responses arose regarding the use of IR light therapy. In general, it appeared that those who completed a residency or fellowship considered using more advanced interventions (i.e., IR light therapy) more often than those who did not. Residency or fellowship programs allow for more training in specified fields, and as such, might expose individuals to such therapeutic interventions and their application more often. Interestingly, ATs considered using such advanced therapeutic intervention even more frequently than residency or fellowship-trained PTs. This could be due, in part, to the site of work that many of the AT respondents work in. Many noted working in a sports team facility or academic institution, which, as discussed above, may allow for more access to such therapeutic interventions.

Despite instructing respondents to omit obvious contraindications (i.e., open wounds, bruises, neurological deficits, etc.) in their consideration of use, many participants continued to list symptoms to be excluded. For example, in the fourth round of survey questions, respondents listed the following as reasons to not use a particular therapeutic intervention: “healing wounds or active fracture,” “neurological deficits,” “open wounds,” “tumor/cancer,” and “recent surgery.” Additional reasonings cited for not considering certain interventions related to patient presentation and/or preference. While it is not known why some therapeutic interventions had lower consensus than others, such factors discussed throughout this section may have influenced this outcome.

One notable limitation of this study is the overall lack of diversity in the sample. Of those that responded, over 85% were white, over 80% described their ethnicity as non-Hispanic/Latino, and over 85% self-identified as men. While the racial/ethnic makeup of the sample largely reflects that of the PT and AT professions as a whole, the gender disparity is greater than what would be expected.25,26 Men in this sample were largely overrepresented, which may mean that the opinions of their female counterparts could be lacking, misrepresenting the true consensus in the field of PT and/or AT. Additionally, it was difficult to recruit and limit the attrition of individuals throughout the study. The limited sample size certainly impacted the generalizability of the results to the greater population of PTs and ATs. Lastly, the classification of use was increasingly broad with each round. This makes it difficult to definitively determine when clinicians would prioritize such therapeutic interventions in absolute terms. As noted before, however, treatment selection is often based on individual patient presentation. As such, it would be irresponsible to declare that a particular therapeutic intervention would be appropriate in all or no instances.

The present study addresses only five interventions that clinicians may use to address recovery and pain management strategies presented here. The therapeutic interventions investigated were selected for their relative affordability and use in treatment spaces. In addition, these interventions are becoming increasingly portable, allowing for their use to be more widespread. Lastly, this Delphi study focuses on several therapies that have emerged over the last decade and are now commonly used by everyday consumers. Elucidating the consensus for practice by professionals could provide a more equitable knowledge base for the common person to use interventions in addressing the complaints addressed here.

CONCLUSION

As is typical among many healthcare professionals, the selection of treatment often relies predominantly on patient presentation with other factors such as the care facility’s access or availability of equipment. Here expert consensus is provided regarding the use of different therapeutic interventions to aid in patient management, athlete preparation, and recovery. Understanding when such interventions could be considered for treatment can help provide guidance as to when to utilize these interventions in patient management. According to the current results, clinicians would consider using: 1) percussive, local vibration, and local heat therapy in the preparation for physical activity; 2) percussive, local vibration, and local cryotherapy in recovery from physical activity; 3) local cryotherapy for the treatment of acute joint pain and acute soft tissue/muscle pain; 4) local heat and local cryotherapy for the treatment of chronic joint pain; and 5) percussive, local vibration, local heat, and local cryotherapy in the treatment of chronic soft tissue/muscle pain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Timothy Roberts and Kyle Silvey are both employed by Therabody Inc. (Los Angeles, CA). Bailey McLagan, David Erceg, Jonathan C. Sum, and E. Todd Schroeder accepted honorariums. The authors acknowledge that Therabody produces devices that use the interventions discussed in the study.