INTRODUCTION

Achilles tendinopathy is a common overuse injury in which loading activities such as running, jumping, and walking elicit pain in the Achilles tendon. This injury is common in both active and sedentary populations,1–3 and negatively impacts physical activity levels,4 work participation,4,5 and overall quality of life.4–6 Tendon recovery is slow, with estimation of full recovery from tendinopathy taking up to one year.7 Individuals who seek treatment present with large variations in symptom duration (a few months to years).8 While most individuals have significant improvement with the gold standard treatment, progressive loading exercises, up to 30% of individuals do not experience full symptom relief.9–11 The continued pain experienced by nearly a third of individuals with Achilles tendinopathy is concerning given that chronic pain, often defined as pain present for more than three months,12 may be related to altered pain processing by the central nervous system.13 Consequently, there is a concern that prolonged or chronic symptom duration in those with Achilles tendinopathy may be related to a central pain issue, such as central sensitization, rather than a peripheral pain issue.

Central sensitization is defined as the hyperexcitability of neural signaling in the central nervous system resulting in pain hypersensitivity to both painful and nonpainful inputs.13,14 Commonly, those with central sensitization have pain for prolonged periods of time and the pain experienced is not in proportion to the tissue injury or lacks nociceptive input entirely.14 This mismatch suggests maladaptive changes or dysfunction within the central nervous systems’ processing of pain.14 Central sensitization is common in those with musculoskeletal injury, and can be problematic as its presence is associated with poor outcomes following treatment14–19 and worse quality of life.14,20,21 Therefore, it is beneficial to proactively identify the presence of central sensitization in patients in order to ensure appropriate treatment strategies.14,18 Given the long symptom duration observed in Achilles tendinopathy and that approximately 30% do not respond to gold standard treatment, it is important to evaluate if central sensitization is present in this population, and if central sensitization correlates with symptom duration. Additionally, symptom severity and pain intensity are commonly evaluated by clinicians treating patients with Achilles tendinopathy. Understanding whether high symptom severity or pain intensity relates to central sensitization may aid clinicians in identifying individuals who may have central sensitization contributing to their symptoms.

Current literature on the presence of central sensitization and its relationship with symptom duration among those with Achilles tendinopathy is mixed. Studies report 6-49% of those with Achilles tendinopathy meet the criteria for central sensitization based on screening questionnaires, such as the Central Sensitization Inventory (CSI) part A.22–24 Other studies conclude central sensitization, as measured by quantitative sensory testing, is not present in individuals with Achilles tendinopathy.25,26 Further, the relationship between symptom duration and central sensitization is reported to have either no correlation or a weak positive correlation.8,22,27 Collectively, the inconsistencies in the literature regarding the presence of central sensitization and its relationship with symptom duration in Achilles tendinopathy may be attributed to differences in methodology, such as the use of screening tools versus quantitative sensory testing. Additionally these inconsistencies may arise from the common practice of pooling data from individuals with tendinopathy at different body regions to achieve larger sample sizes.8,22–24,26,27 Pooling data of tendinopathies from different locations is problematic as prior evidence shows pain processing differs in tendinopathies in the in the upper and lower extremities.8,26 Even within the same body region, pain processing in the Achilles tendon differs from other foot tendinopathies.27 Therefore, there is a need to evaluate the presence of central sensitization and the relationship between symptom duration and central sensitization in a single, large cohort of a tendinopathy at a single location.

The purpose of this study was assess the proportion of individuals with midportion Achilles tendinopathy who may have central sensitization, as defined by the CSI part A questionnaire.28 A secondary aim was to assess the relationship between symptom duration, pain intensity, symptom severity and CSI scores.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional study using the baseline data from a longitudinal clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT03523325) assessing sex differences in the response to treatment for midportion Achilles tendinopathy.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for the study were individuals between the age of 18 and 65 years with a clinical diagnosis of midportion Achilles tendinopathy. The diagnostic criteria were based on participant report of symptoms and presence of pain in the midportion of the Achilles tendon with activity. The diagnosis was confirmed with clinical diagnostic tests.7 Exclusion criteria were having insertional Achilles tendinopathy, history Achilles tendon rupture, recent steroid injection to the Achilles tendon, or injury which prevented participation in the exercise program or testing protocol. Participants were enrolled from July 2018 through February 2023. Prior to participant enrollment, the study was approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board and participant informed consent was obtained. One hundred and eighty-two individuals (79 males, 103 females) were included for this analysis. Data used in this study came from an existing study, therefore no a priori power analysis was performed. Power calculations for the original study indicated a sample of at least 160 people was required for its primary aims.

Demographics

Patient information, including, age, sex, past medical history, and information relating to their current injury was collected through questionnaires. Current injury data included date of symptom onset, and affected side (left, right, or both). If bilateral symptoms were present, participants self-selected what side was more symptomatic. Height and weight were measured and used to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI).

Symptom Duration

Symptom duration was measured as the time (months) between the self-reported date of symptom onset and the day of study enrollment.

Central Sensitization Inventory

The CSI part A28 was utilized to determine a likely presence of central sensitization in study participants. CSI part A is a patient reported outcome measure made up of 25 questions which assess different symptoms commonly associated with central sensitization,28 and is a valid28 and reliable29 questionnaire. Each question asks the frequency of a symptom on a 0 (never) to 4 (always) Likert scale. The sum score is between 0 and 100 with a higher score indicating a higher frequency of symptoms.28 A score of greater than or equal to 40 on the CSI has been previously established as a cutoff score distinguishing between those with and without conditions stemming from central sensitization.29 This cut off score had high sensitivity (81%) and an acceptable level of specificity (75%).29 Therefore, in alignment with the previous literature, scores greater than or equal to 40 to indicate the participant may have central sensitization present were used in the present study.

Symptom Severity

The Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Achilles (VISA-A)30 was used to determine symptom severity. The VISA-A is a valid and reliable patient-reported outcome measure designed to assess symptom severity in those with Achilles tendinopathy.30 This questionnaire is also one of the core outcomes for evaluation of Achilles tendinopathy in both clinical and research settings.31 While this questionnaire was originally developed for sport assessment, it has been used in numerous studies with athletic and non-athletic samples.32 Scores on the VISA-A range from 0 to 100 with lower scores indicating more severe symptoms.30 The VISA-A score for the self-reported most symptomatic side was used in the analysis.

Pain Intensity

The pain intensity item from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 29 (PROMIS-29) was used to represent participants’ average pain intensity.33 The question asks participants to rate their average pain intensity in the past seven days on a 0-10 visual analog scale, with 10 indicating the worst imaginable pain. The PROMIS-29, including the pain intensity item, are valid and reliable in evaluating health-related outcomes.33

Statistical Analysis

Study data were collected, managed, and de-identified using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University of Delaware.34,35 Descriptive statistics for demographic variables, including percentage of participants with bilateral symptoms and average symptom duration are reported. Bivariate Pearson correlations were used to assess the relationships between symptom duration, CSI score, VISA-A, and pain intensity. Interpretation of correlation values were made based on Schober and Schwarte.36 All statistical tests were performed in IBM SPSS version 29.0.1.0.

RESULTS

Participant demographics for the 182 participants included are presented in Table 1.

Symptom Duration and Central Sensitization Inventory

Nine of 182 (4.9%) individuals in the current study met the clinical cut off on the CSI (greater than or equal to 40). All nine individuals were female (Figure 1). There was no correlation between symptom duration and CSI score (r = 0.037, 95% CI [-0.109, 0.181] p=0.622) (Figure 2). Symptom Duration and CSI are reported in Table 2.

VISA-A, PROMIS Pain Intensity and CSI

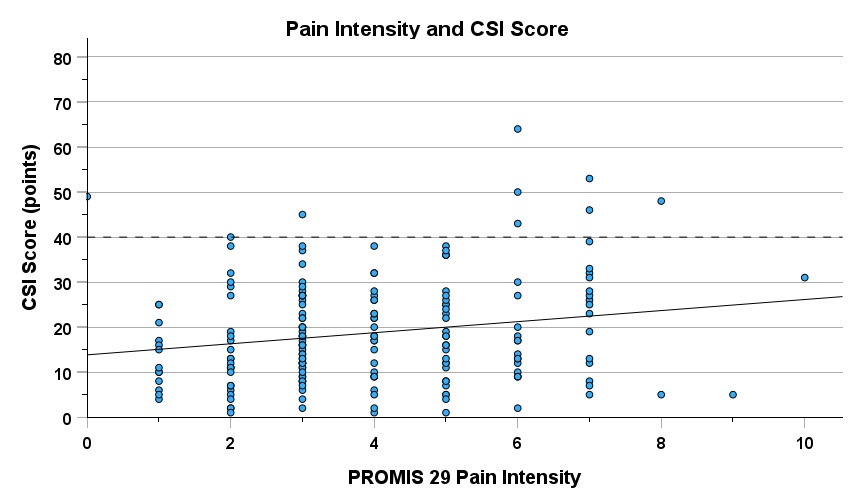

There was a significant weak negative relationship between VISA-A on the most symptomatic limb and CSI score (r = -0.293, 95% CI [-0.420, -0.154] p< 0.001), meaning, the lower (i.e. worse) the symptom severity score, the higher the CSI score (Figure 3). There was a significant weak positive correlation between PROMIS pain intensity and CSI score (r = 0.195, 95% CI [0.051, 0.331] p = 0.008), meaning the higher (i.e. worse) the average pain rating, the higher the CSI score (Figure 4). VISA-A and PROMIS Pain Intensity are reported in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the number of individuals with midportion Achilles tendinopathy who score above the clinical cut off on the CSI, and to determine if symptom duration, symptom severity, or pain intensity correlated with CSI score. In this large cohort (n=182), less than 5% of the individuals with midportion Achilles tendinopathy scored above the CSI cutoff score (notably all were females), indicating a likely presence of central sensitization. Additionally, symptom duration did not relate to CSI score. However, higher symptom severity and pain intensity was correlated with a higher CSI score. Based on the present findings, prolonged duration of symptoms may not be a contributing factor to central sensitization in individuals with midportion Achilles tendinopathy.

There is a concern that prolonged symptom duration, commonly observed in Achilles tendinopathy, may alter pain processing and lead to the development of central sensitization. In turn, altered pain processing may partially explain why nearly one third of individuals with Achilles tendinopathy do not respond to gold standard treatment. Participants in the present study had a wide spread of symptom duration (five days to 274 months), which is representative of this population.8 The findings in the present study suggest longer symptom duration among those with midportion Achilles tendinopathy does not relate to increases in central sensitization type symptoms, as assessed by the CSI. These findings are consistent with previous literature which suggests pain associated with Achilles tendinopathy is likely a peripheral nociceptive pain condition.25–27 Pain associated with midportion Achilles tendinopathy is typically intermittent, waxing and waning over periods of time,37 or only evoked with lower extremity loading. Given these periods without pain, or the absence of pain at rest, it is possible an alteration in pain processing does not occur in those with midportion Achilles tendinopathy as it does in other conditions, such as low back pain or knee osteoarthritis, where pain is typically more constant.38

Less than 5% of individuals with midportion Achilles tendinopathy in the current study likely have central sensitization contribution present, per the CSI. This finding is consistent with Wheeler,22 who reported 6.1%, in a sample of 33 individuals with non-insertional tendinopathy, met the clinical cut off score for the CSI.22 The average CSI score in the present study’s sample was low, at about half the value of the clinical cut off score. Despite the low average, there was still a significant correlation between both average pain intensity and symptom severity with CSI score. However, the correlations were both weak.36 Therefore, high symptom severity or pain intensity in those with midportion Achilles tendinopathy are unlikely to be strong indicators to clinicians in identifying individuals who may have central sensitization contributing to their clinical presentation.

It was not surprising that only females scored above the clinical cut off on the CSI, since previous literature indicates healthy and injured females report more pain or greater pain intensity than their male peers.39,40 Females also make up a larger proportion of those diagnosed with chronic pain conditions.39,40 Previous literature indicates females with musculoskeletal injuries tend to score higher on the CSI compared to males with the same musculoskeletal injury.22,41,42 Therefore, the findings from the present study may reflect that females are more likely to have central sensitization or report more pain than their male peers.40 There is a paucity in the Achilles tendinopathy literature which evaluates sex differences in pain with this injury.43 Overall, these findings support the need to further evaluate sex differences as it relates to pain in those with Achilles tendinopathy.

Limitations

The current study is not without its limitations. Since the CSI is a screening questionnaire, it cannot be used for the diagnosis of central sensitization.28 Instead, scoring at or above the clinical cut off of 40% indicates likely presence of central sensitization and suggests further evaluation to diagnose central sensitization.28,29 However, the findings are consistent with the Plinsinga et al. in which quantitative sensory testing, a common method to evaluate for central sensitization, were used to conclude that Achilles tendinopathy is predominately a peripheral pain state.25 Additionally, while the CSI has been validated in numerous musculoskeletal pain populations,42,44 it has yet to be validated specifically for Achilles tendinopathy. However, a strength of the current study is that it evaluated central sensitization in a large sample from a single study cohort with the same type of tendinopathy. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the largest single cohort study to evaluate the CSI, or any measurement of central sensitization, among those with midportion Achilles tendinopathy.

CONCLUSION

Less than 5% of participants with midportion Achilles tendinopathy in the present study scored above the clinical cut of score on the CSI, indicating likely presence of central sensitization. Symptom duration in those with midportion Achilles tendinopathy did not relate to CSI score. Collectively, findings from the current study indicate that prolonged symptom duration in those with midportion Achilles tendinopathy is unlikely to lead to the development of symptoms associated with central sensitization. The pain associated with midportion Achilles tendinopathy may have a stronger association with peripheral pain mechanisms rather than central pain mechanisms.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no disclosures to report

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers: R01-AR072034 and T32HD007490. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported in part by a Promotion of Doctoral Studies (PODS) – Level I Scholarship from the Foundation for Physical Therapy Research.

_score_by_sex._clinical_cut_off_score.png)

_score._cli.png)

_in_the_most.png)

_score_by_sex._clinical_cut_off_score.png)

_score._cli.png)

_in_the_most.png)