Introduction

Meniscus surgery is one of the most common procedures performed all over the world. The indications of treatment and practice have evolved with time due to the improved knowledge of the biomechanics of the meniscus and the consequences of extensive meniscectomies.1 Recent studies focus on the indications for surgery, and if needed, which surgery preserves as much meniscus tissue as possible while providing the best short and long-term functional results.

Following these trends, ESSKA (European Society for Sports Traumatology and Arthroscopy) initiated the European Meniscus Consensus Project in 2016.2 The aim of the first part was to provide a reference document for the management of Degenerative Meniscus Lesions (DML), based both on scientific literature and balanced clinical expertise. Following this, arthroscopic partial meniscectomy became not a first, but a second line treatment for treating DML. In 2019, the second ESSKA meniscus consensus3 provided recommendations for the surgical treatment of Traumatic meniscus tears. The main message of this second consensus was that preservation of the meniscus (including repair or partial meniscectomy) should be the first treatment philosophy for traumatic tears. Postoperative rehabilitation after meniscus surgery may vary with time, location/country, expertise and habit. Detailed rehabilitation decisions were not covered by the previous consensuses.

For anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, robust rehabilitation protocols and recommendations exist.4,5 For the meniscus, literature is still scarce.6–8 While many indications and techniques of meniscus surgery are made based on sufficient evidence, many surgeons, sports medicine doctors and physiotherapists still face multiple options where recommendations are lacking, especially for the postoperative care after meniscus surgery. That is the reason why ESSKA, AOSSM (American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine) and AASPT (American Academy of Sports Physical Therapy), three main scientific societies working around meniscus pathology and rehabilitation, decided to cover the topic together, in order to give unified messages.

The aim of this formal consensus was to provide recommendations for the usage of rehabilitation (including physical therapy) for patients with symptomatic menisci. The first part of the consensus will focus on rehabilitation performed after any surgical treatment for degenerative meniscus lesions, traumatic meniscus tears (meniscectomy or repair), or meniscus reconstruction.

The second part of the consensus will cover prevention, non-operative treatment and return to sport modalities. The full version of the consensus project can also be read in more detail on the ESSKA website (https://esskaeducation.org/esska-consensus-projects) and on the ESSKA Academy Website (Open Access) https://esskaeducation.org/sites/default/files/2024-07/The formal EU-US Meniscus Rehabilitation Consensus.pdf.

Material and Methods

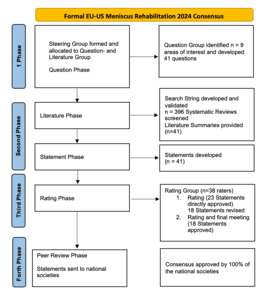

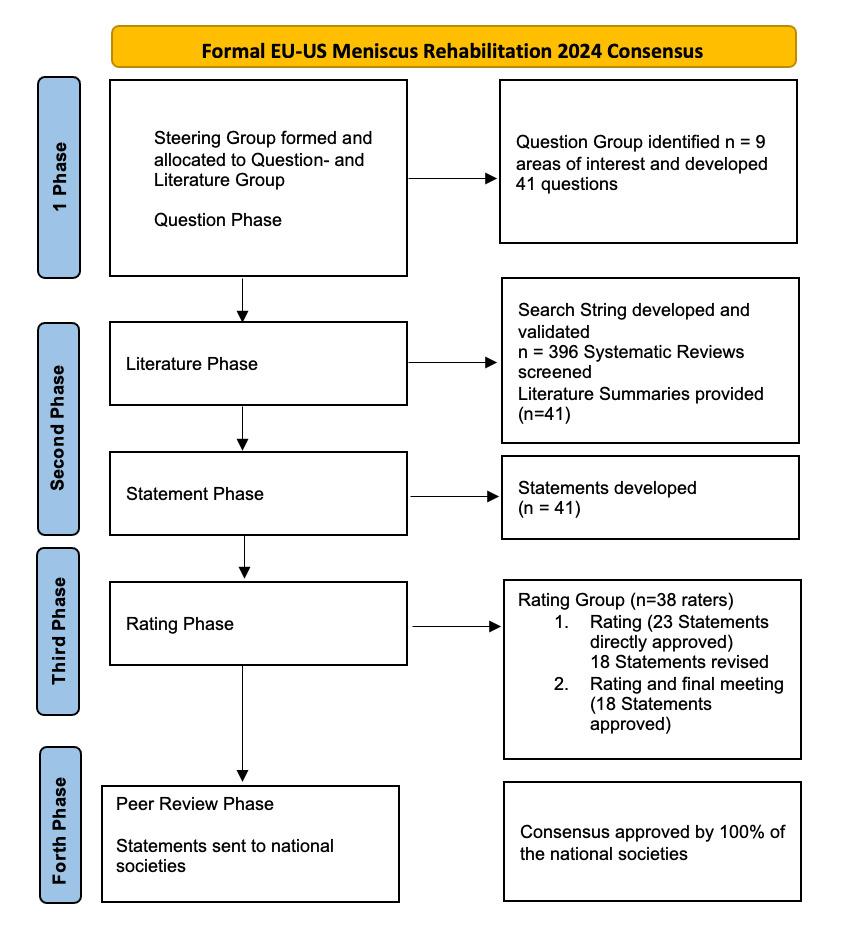

An EU-US consensus project was established by ESSKA-AOSSM and AASPT between 2022 and 2024, focusing on the rehabilitation management of meniscus tears. Prevention, non-operative, and post-operative management for both degenerative meniscus lesions or acute tears (meniscectomy, repair, reconstruction), return to sports, and patient related outcomes were considered in this project.

The process and methodology of this consensus project were similar to previously published ESSKA consensus projects.9,10 Chairs were nominated by the ESSKA board. A steering group was built with experts in the field of meniscus and rehabilitation. The steering group was divided in two groups, one being mainly responsible for developing questions and statement drafts

(question group) and the other one for screening the current literature and providing evidence to support the development of statements (literature group).

The consensus equally involved Orthopedic Surgeons, Physiotherapists and Sports medicine practitioners, equally distributed among USA and Europe, equally selected by AOSSM and AASPT. First, the question group queried relevant topics in the field. According to the questions, literature was searched and summarized by the literature group. This comprehensive search was performed on MEDLINE (Pubmed), Web of Science, and SCOPUS databases without time constraint for the search. All clinical studies were included (randomized and non-randomized clinical trials, multicenter studies, reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses). The process was restricted to English language. Search String was validated by the group and is provided as Supplement 1.

Overall, 395 relevant papers were screened and included, and additional literature was manually searched. Each bibliography of the full-text articles was screened by hand for inclusion. Any disagreements were discussed and settled between the members of the literature group. After review of the literature, the question/statement group formulated recommendation statements to answer the agreed upon questions and added grading according to the level of evidence supporting the statements. Grade A was defined as a high level of scientific support, Grade B as a scientific presumption, Grade C as a low level of scientific support, and Grade D as an expert opinion. After recommendations were completed, an independent rating group rated the statements according to scientific quality and clinical experience using the Likert scale (ranging from 1to 9 (i.e. totally

inappropriate to totally appropriate). Final agreement was classified as high (median value ≥ 7 and the ratings were all ≥ 7) or Relative (median value ≥ 7 all scores >5.

At the end of the first round, 19 questions (29 statements overall) focusing on rehabilitation after meniscus surgery were formulated by the steering group. A revised manuscript draft was prepared and resubmitted to the rating group for a second assessment for any statements where the median agreement was below 7. The same level of agreement was applied for the second round. A combined steering-rating group meeting allowed to finalize the last version of the document.

The last version of the manuscript was finally reviewed by representatives of the affiliated scientific societies of ESSKA, AOSSM and AASPT to produce the final consensus statement. The aim of this last step was to check the geographic adaptability and clinical clarity for world-wide use. The process is displayed in a flowchart (Figure 1).

Results

Of the 19 questions (leading to 29 statements), one received a grade A rating, two a grade B, nine a grade C and 17 a Grade D. This means that low to moderate scientific level of evidence was available in the current literature for making most of the statements and the weight of clinical expertise in the statements set up. 6 questions went onto a second revision and rating. Overall, the mean median rating was 8.2/9 (8-9) and the global mean rating was 8.3+/-0.2/9, meaning that the global agreement between experts was high.

A) Rehabilitation management after partial meniscectomy

- What rehabilitation treatment is best indicated for the management of patients after isolated partial meniscectomy? Is there an evidence-based treatment protocol?

No evidence-based treatment protocol exists. A criterion-based rehabilitation protocol, based on milestones, is recommended. Following partial meniscectomy, immediate full weight-bearing and full range of motion are permitted as tolerated per symptoms (Grade C).

Although large effusions are uncommon after partial meniscectomy, they occasionally do occur and can lead to significant quadriceps inhibition that may require use of an assistive device, particularly in older people and those with high BMI or other comorbidities (Grade D).

To address quadriceps strength and neuromuscular control deficits, the use of NMES (Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation), OKC (Open Kinetic Chain), and CKC (Closed Kinetic Chain) strengthening is recommended as is seen in similar patient populations (i.e. after ACL reconstruction) (Grade C). Mean 8.4+/-1.45, Median 8 (5-9), Relative agreement.

- Is there a difference between rehabilitation proposed after medial or lateral partial meniscectomy)?

There are no specific rehabilitation protocols after medial or lateral partial meniscectomy. More adverse events (persisting swelling and pain, risk of early chondrolysis) may happen after lateral partial meniscectomy which may result in delayed return to higher impact activities and sports compared to medial partial meniscectomy (Grade D).

Agreement: Mean 7.8+/-1.36, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- Is there any difference between traumatic meniscus tears and degenerative meniscus lesions in terms of rehabilitation after partial meniscectomy?

There is no comparative data to support any difference between rehabilitation protocols for partial meniscectomy for degenerative lesions and traumatic tears. Rehabilitation protocols can vary based on patient factors and the status of the knee post-operatively. Partial meniscectomy for degenerative lesions may require slower rehabilitation progression (Grade D).

Agreement: Mean 8.3+/-1.51, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- Should non-weight-bearing or partial weight-bearing be recommended after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy?

After arthroscopic partial meniscectomy full weightbearing is allowed early after surgery (Grade A).

The usage of crutches may be recommended for mobility until gait is normalized (Grade D). Agreement: Mean 8.4+/-1.00, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- For how long is rehabilitation recommended after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy? What persisting signs and/or symptoms during rehabilitation require a referral to a surgeon (for example, includes time from injury or surgery, ROM (Range of motion), pain, swelling, and activity limitations)?

There are multiple rehabilitation guidelines for return to walking, work and sport with timeframes often ranging between 4 and 12 weeks. However, rehabilitation after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy should be criterion based and not time based. Return to these activities requires meeting progressive milestones throughout rehabilitation (e.g., effusion, range of motion, quadriceps strength, neuromuscular control) and not just meeting healing time frames (Grade B).

Patients should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon in cases of persistent pain, recurrence of stiffness and/or effusion, persistent functional instability, mechanical symptoms, any neurological symptoms, suspicion of infection or DVT (Distal Veinous Thrombosis) (Grade B).

The inability to reach clinical milestones related to knee symptoms indicates a referral to the orthopedic surgeon (Grade D).

Agreement: Mean 7.8+/-1.02, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

B) Rehabilitation management after meniscus repair

- What rehabilitation treatment is best indicated for the management of meniscal repair? Is there an evidence-based treatment protocol?

Whilst no evidence-based rehabilitation protocol has been shown to be superior to another, postoperative rehabilitation should consider the meniscal tear pattern and zone of injury, tissue quality and vascularity, surgical repair technique, repair stability and any patient specific characteristics known to influence the surgical prognosis (Grade D).

For isolated meniscal repair, no evidence exists for the use of specific rehabilitation protocol or adjuvant therapies. For knee surgeries where there is concomitant meniscal repair NMES, in the early post-operative phase, may help in recovery of quadriceps activation (Grade D).

Combined time and criterion-based protocols can be recommended. Management of effusion should be addressed in the protocol (Grade D).

Rehabilitation should be progressed according to both time and criterion-based milestones. A minimum of 4-months of rehabilitation may be recommended for repaired vertical tears of the meniscus, whereas complex, complete radial/root, and horizontal tears may require a longer duration of rehabilitation (i.e., 6 to 9 months) (Grade D).

Agreement: Mean 8.3+/-1.59, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- How does location of meniscus tear/repair (i.e. stable, unstable, root tear, complex tear, white zone tear, etc.) influence the progression of rehabilitation after repair (i.e. ROM, weightbearing, loading activities)?

For vertical longitudinal tears full weight-bearing may be recommended, with a limitation of ROM for 6 weeks. For ramp lesions the rehabilitation protocol is driven by associated procedures (e.g., ACL reconstruction) (Grade C).

Limitation of weight-bearing, and ROM for 4 to 6 weeks is recommended for complex, horizontal, radial, and root repairs (Grade C).

Following repair-specific early post-operative restrictions in ROM and weightbearing, rehabilitation after meniscus repair should follow criterion- and time-based components. Return to activities requires meeting progressive milestones throughout rehabilitation (e.g., effusion, range of motion, quadriceps strength, neuromuscular control) and meeting healing time frames. This is different from arthroscopic partial meniscectomy, which is criteria based (Grade D).

Agreement: Mean 7.2+/-1.96, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- Are there specific exercises that should be avoided following all meniscus repair (e.g. deep loaded flexion – e.g. deep squats)? If so, then for how long?

Deep squatting, jumping (deep loaded flexion) and rotational knee movements activities should be avoided for a minimum of 4 months. For vertical longitudinal tears, mini squats up to 30° can be recommended from week 4-8, up to 45° from week 8-12 and up to 60-90° from week 13-16 (Grade D).

Agreement: Mean 7.6+/-1.34, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- Does a medial and lateral repaired meniscus tear require different protocols?

Medial and lateral meniscal repairs may be rehabilitated similarly, with the tear type (radial, root, vertical) influencing rehabilitation rather than laterality (Grade C).

Agreement: Mean 7.8+/-1.70, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- For how long rehabilitation is recommended after meniscus repair?

Rehabilitation after meniscus repair should be both criterion and time based according to the healing process. A minimum of 4 months of rehabilitation may be advised for repaired vertical meniscus tears. Complex, radial, root, horizontal tears may require a longer rehabilitation, up to 6 to 9 months (Grade D).

Agreement: Mean 8.5+/-, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- What are the criteria-based recommendations after meniscus repair?

Rehabilitation following meniscal repair should be divided into protective, restorative, and preparation to return to activity and sports phases, with additional criterion-based goals recommended. Criteria for progression to the restorative phase of rehabilitation include full or nearly full passive ROM, no effusion, and neuromuscular control of the quadriceps. Initiation to return activity phase of rehabilitation begins once the patient demonstrates full active ROM, strength (larger or equal to 80% of contralateral leg would be ideal), and adequate single leg dynamic knee control. Progression of quadriceps strength is recommended to be tested at each phase of rehabilitation via the use of isokinetics or appropriately stabilized handheld dynamometry (Grade D). Agreement: Mean 7.9+/-1.44, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- Does concomitant ACL reconstruction have an impact on rehabilitation after medial or lateral meniscus repair when compared to meniscus repair on a stable knee?

Rehabilitation protocols for repaired menisci with concomitant ACL reconstruction are similar to protocols for isolated meniscal repairs; however, return to sport may be delayed on account of the ACL reconstruction. Meniscus repairs requiring limitation of weight-bearing and/or ROM would affect ACL rehabilitation protocols. Most stable vertical meniscal tear repairs do not affect ACL rehabilitation protocols (Grade C).

Agreement: Mean 8.1+/-1.39, Median 9 (6-9) , Relative agreement.

- Questions for all repaired meniscus lesions:

-

Should non-weight-bearing or partial weight-bearing be recommended after meniscus repair (for lateral or medial meniscus)? If yes, for how long?

-

If full weight bearing is allowed, is the usage of crutches recommended after meniscus repair? If so, for how long crutches should be used?

-

Is there any restriction in terms of range of motion in the post-operative period?

-

Is there any indication for a knee brace after meniscus repair in the post-operative period (locked brace or soft brace)?

- There are different categories of repaired traumatic meniscus tears, and a specific rehabilitation protocol should be considered for each of them (Grade C).

Agreement: Mean 7.3+/-1.42, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

Two Summary tables are provided (Tables 1 and 2).

C) Meniscus reconstruction (transplantation or scaffold):

- Is there any difference between different types of meniscus reconstruction (transplantation or scaffold) in terms of rehabilitation management?

Scaffolds and Allografts rehabilitation protocols follow the same rules and restrictions (Grade D). Agreement: Mean 7.6+/-1.82, Median 8 (5-9) , Relative agreement.

- What rehabilitation protocol is best indicated for the management of meniscus reconstruction (transplantation or scaffold)?

Rehabilitation after meniscus reconstruction should be criterion and time based. Different stages of rehabilitation are an early protective phase, followed by an intermediate restorative phase, and finally a return to activity phase. Progression through phases will vary significantly for each patient based on associated procedures, level of activity, and individual rates of recovery. Rehabilitation protocols could follow those of meniscus root repair (two roots are repaired after MAT), which require up to 9 months (or more) of rehabilitation. The consensus group suggests return to sports at 12 months or more (Grade D).

Agreement: Mean 8.4, Median 9 (7-9), Strong agreement.

- Is there a difference between rehabilitation proposed after medial or lateral meniscus reconstruction (transplantation or scaffold)?

Similar rehabilitation protocols can be used for medial or lateral meniscus reconstruction (Grade D). Agreement: Mean 7.9+/-1.00, Median 8 (6-9) , Relative agreement.

- What are the weightbearing precautions recommended after meniscus reconstruction (transplantation or scaffold)?

Early weight-bearing has been shown to increase the risk of meniscus extrusion after meniscus reconstruction. Therefore, non-weight-bearing is recommended for 6 weeks, progressing to full weight-bearing gait after 8 weeks. Weight bearing status may also be affected by other concomitant procedures such as osteotomy, cartilage, or ligament surgeries. Weight bearing through a flexed knee (example: stairs, squatting, lunging) should be delayed. Initial weight bearing should occur in relative knee extension, such as with gait and standing (Grade C).

Agreement: Mean 8.1+/-1.46, Median 9 (7-9) , Strong agreement.

- Should the range of motion be restricted in the postoperative period after meniscus reconstruction (transplantation or scaffold)? If yes, for how long?

90 degrees of non-weightbearing flexion should not be exceeded until 6 weeks postoperatively. Associated surgical procedures may alter further ROM restrictions (Grade D). Agreement: Mean 8.1+/-1.21, Median 8 (6-9) , Relative agreement.

- Is a brace useful after meniscus reconstruction (transplantation or scaffold) in the post operative period (postop/unloading or functional for return to activity)?

There is a lack of evidence for bracing after meniscus reconstruction. The consensus group has no recommendation on the use of a knee brace. The use of a knee brace after meniscus reconstruction surgery is dependent on surgeon preference and concomitant procedures (Grade D). Agreement: Mean 8.3+/-1.11, Median 9 (6-9) , Relative agreement.

Discussion

The most important message of this consensus is that moderate to low scientific level of evidence was available in reference to rehabilitation after meniscus surgery. Meniscus pathology is common; however, it is not often studied in isolation. Nevertheless, our recommendations are based on this literature and on the input of experts of three different specialties (orthopedic surgeons, physiotherapists and sports physicians) from 2 continents (Europe and USA), with a good agreement of the proposed statements.

The primary outcome of the consensus indicated that any patients undergoing meniscus surgery would benefit from rehabilitation. Rehabilitation protocols vary according to the type of surgery performed. More research is needed specific to meniscus rehabilitation.

After meniscectomy

Knee pain, lack of mobility, effusion, and quadriceps weakness are the most common clinical findings after a partial arthroscopic meniscectomy procedure. Regaining quadriceps strength is of utmost importance.11

So, a criterion-based rehabilitation protocol, based on milestones, is recommended. A systematic review that included 18 randomized controlled trials out of which 6 were pooled in meta-analysis, was published in 201312 and highlighted already this point

When comparing outpatient physical therapy with home exercise to home exercise alone, significant improvement was found in favor of the outpatient physical therapy group for the outcome of patient-reported knee function on the Lysholm questionnaire, and for the knee flexion ROM. Expert opinion advocated that the treatment should include outpatient care and a home exercise program. The following interventions are advised: early weight bearing, progressive knee mobilization exercises, quadriceps and hamstrings strengthening exercises (isometric and dynamic), sensory motor training, thermotherapy, and an early return to activities. It may use adjuvants such as neuromuscular electrical stimulation, EMG biofeedback, and isokinetics.12

After meniscus repair

Rehabilitation should be adapted to the type of repaired lesion, whatever the meniscus treated (lateral or medial) and whatever the status of the ACL (reconstructed or stable), following time-based (to favor meniscus healing) and criterion-based protocols.

Regarding root tear repair there have been no long-term studies comparing the efficacy of varying rehabilitation protocols for patients recovering from meniscal root repairs, especially regarding the time course for introducing weight-bearing, increasing ROM and beginning strength training. Nonetheless, biomechanical models of cyclic loading have underscored the need for more gradual and cautious rehabilitation protocols compared with other types of meniscal lesions.13,14

With radial/root repairs of meniscus, a strict emphasis on non-weight bearing should be implemented for the first 6 weeks, during which time, range of motion should also be limited to 90 degrees.15

One systematic review evaluated the management of ramp lesions. Seven studies have been analyzed, 2 RCT and 5 retrospective case series. At least 2 weeks of non-weight bearing were indicated in all the studies, full weight bearing (FWB) was permitted between 4 and 12 weeks. All authors allowed immediate postoperative passive joint movements from 0° to 90° to avoid stiffness. At 6 weeks after surgery, a full range of motion was permitted. The use of brace was prescribed in 181 (41%) of cases.16 The literature with higher levels of evidence seem to support weight bearing as tolerated with no specific indications about crutch weaning.17–19

Even individually analyzing all the papers of a systematic review about comparison of accelerated and conservative rehabilitation protocols, we cannot draw strong conclusions: some authors do not specify details on crutch use, and when it is specified, there are no clear indications about the duration of use.19 Nevertheless, the recommendations of the consensus group is summarized in Table 1.

Concerning longitudinal/vertical tears, the literature17–19 supports free motion as tolerated as soon as possible after surgery. Deep squats may be restricted initially. No standardized indications were found about the use of a knee brace. In the protocols in which range of motion and weight bearing are restricted the brace is indicated for a 3 to 6 weeks postoperative period. In more accelerated protocols, the use of the brace is not routinely mentioned. The authors that mention it describe its use for the first postoperative days in some cases or for the first weeks only to protect the knee during weight bearing.

After meniscus allograft transplantation

There are no high-level studies available to guide the direction of rehabilitation in this setting. The literature focuses mainly on indications, technique, outcomes, complications and return to sport with little being reported on the effect of rehabilitation management or differing strategies.

Nevertheless, experts’ opinions and literature review give similar proposals. Patients who undergo meniscal allograft transplantation are recommended to follow a dual restriction protocol20 time based, and criterion based. Biology and graft maturation may be of importance, so recovery may be slower than other meniscus procedures (meniscectomy or repairs).21

Rehabilitation is based on active and passive exercises depending on the time after surgery, with rehabilitation guidelines and goals being more delayed than accelerated.21 Weight bearing is restricted for 6 weeks and return to sports delayed to 9 months, if possible, at all, at a competitive

level.22 We acknowledge that there will be significant variability for each patient based on concomitant procedures, desired level of activity, and individual rates of recovery.23

This consensus has some limitations.

This is not a systematic review and meta-analysis of the entire literature of meniscus rehabilitation. The overall level of evidence of the literature covering meniscus rehabilitation is relatively low. The weight of the clinical expertise is higher when compared with scientific evidence of this topic. However, there are many strengths: This is an international worldwide consensus with a rigorous methodology based on five criteria (1 pluralism, 2 iterative process, 3 refereeing, 4 literature search, 5 transparency) which dramatically reduces the selection and confirmation biases which could appear.9

There is 1) a large pluralism (more than 100 people involved) of the experts, selected according to precise rules.. This is 2) an iterative process with totally independent groups working at different steps (steering and rating groups). These people, by their geographic distribution and medical specialties, do represent exactly the community-target (3 Refereeing). Literature search 4) was performed according to precise rules and by an independent group. All the content of the search (literature summaries and reference list) is available on the website for complete transparency. Finally, this initiative has been done under the umbrella of established scientific societies with the assistance of a “neutral” consensus projects advisor.

Conclusion

Rehabilitation after meniscus surgery is a debated topic that may influence surgical outcomes if not optimally performed. Rehabilitation depends on the type of meniscus tear, the type of surgery, concomitant procedures if any, and criterion-based milestones.

This international EU-US consensus provided an up-to date overview of the best available evidence for clinicians (surgeons, physiotherapists, sport medicine doctors etc.) treating meniscus-injured patients. Take care of the meniscus!

More information about this consensus as well as the complete list of references can be found on the ESSKA website (https://esskaeducation.org/esska-consensus-projects) and on the ESSKA Academy Website (Open Access) https://esskaeducation.org/sites/default/files/2024-07/The formal EU-US Meniscus Rehabilitation Consensus.pdf .

Conflicts of Interest

Nicolas Pujol: occasional consultant for education for Smith&Nephew, Stryker, ZimmerBiomet

Philippe Beaufils : ESSKA Consensus Projects advisor

Stephanie Wong: Editor-in-Chief of Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine

Robert Prill: Associate Editor KSSTA, Chair ESSKA Rehabilitation Committee

Airelle O. Giordano: Education Chair, AASPT

Robert F. LaPrade: Consultant: Smith and Nephew, Ossur; Royalties; Smith and Nephew, Ossur, Elsevier; Research support: AOSSM, AANA, Ossur, Smith and Nephew, Arthrex; Editorial Boards: AJSM, KSSTA, JEO, Journal of Knee Surgery; JISPT, OTSM; AOSSM: Nominating Committee; ISAKOS: Traveling Fellowship Committee, Program Committee

Aaron J. Krych: Consulting and Royalties Arthrex, Inc. Editorial Boards: AJSM, KSSTA. AANA Board.

James J. Irrgang: Currently serve as President of the Board of Directors of Movement Media Sciences/Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy

Alexandre Rambaud : Member of ESSKA Rehabilitation Committee; Deputy Editor: European Rehabilitation Journal, Journal de Traumatologie du Sport, Editor-in-Chief of Kinésithérapie, la Revue

Laura C. Schmitt: Editorial Board: MSSE; Research Support from Arthritis Foundation and NFL Players Association

Jill K. Monson: Member AASPT Research Committee, Consultant Smith & Nephew

Mark V. Paterno: Co-Chair AASPT Research Committee, Research Support from AOSSM/AIrCast Research Foundation.

Simone Perelli: paid consultancy for Smith&Nephew

Aleksandra Królikowska: Member of ESSKA Rehabilitation Committee

Nicky van Melick: Member of ESSKA Rehabilitation Committee

Jitka Klugarová: deputy director of the Czech CEBHC: JBI Centre of Excellence, Czech GRADE Network, member of methodological group withing JBI and GRADE working group.

These other authors did not declare any conflict of interest:

Adam J. Tagliero

Thorkell Snaebjornsson

Marko Ostojic

J. Brett Goodloe

C. Benjamin Ma

R. Becker

JC Monllau

Elanna K. Arhos

Eric Hamrin Senorski

James Robinson

Tomasz Piontek

Emma L. Klosterman

Authors contribution

Nicolas Pujol, Airelle Giordano, Ben Ma and Robert Prill chaired the consensus and have been involved in all parts of the work. Stephanie Wong revised the first draft of this manuscript and was a member of the Steering Group. Phillipe Beaufils is the official ESSKA consensus projects advisor, who advised together with Juan Carlos Monllau Garcia adhering to the official consensus method. All other authors were members of the Steering Group and either developed questions and statements or did sufficient literature work. They are listed in alphabetical order. All authors were involved in the validation process of the statements. All authors read, revised and approved the final draft of this paper.

Funding

This work was not funded. It was supported during the process by the European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy (ESSKA) and the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) Office.

Acknowledgements

To all members of the rating group:

European rating group: C. Bait (Italy), K. Briem (Iceland), P. Epinga (The Netherlands), Ch. Fink (Austria), D. Garcia German (Spain), A. Grassi (Italy), H. Gridem (Norway), G. Harput (Turkey), M. Iosifidis (Greece), C. Juhl (Denmark), E. King (Ireland),T. Lange (Germany), J. Menetrey (Switzerland), B.G. Moatshe (Norway), S. Mogos (Romania), L. Oleksy (Poland), G. Palmas (Italy), Th. Patt (The Netherlands), G. Samitier (Spain), A. Silva (Portugal), J. Stephen (United Kingdom), C. Toanen (France), T. Wörner (Sweden).

US rating group: L. Bailey, T Chmielewski, S. Di Stasi, B. Forsythe, C. Garrison, J. Lamplot, D. Lansdown, A. Lynch, R. Ma, A. Momaya, V. Musahl, K. Okoroha, J. Schoenecker, B. Solie, A. Su, M. Tanaka, E. Wellsandt, G. Williams.

We would also like to thank the peer reviewers from all over Europe and US for their contribution to this consensus.

Also, we would like to acknowledge the help from the ESSKA and AOSSM office, especially Anna Hansen Rak and Lynette Craft.

List of abbreviations

-

ACL : Anterior Cruciate Ligament

-

ADL : Activities of Daily Living

-

AOSSM : American Orthopaedic Society For Sports Medicine

-

ESSKA : Eurpoean Society Of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery & Arthroscopy

-

AASPT : American Association Of Sports PhysioTherapists

-

NEMS : Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation

-

OKC : Open Kinetic Chain

-

CKC : Closed Kinetic Chain

-

ACLR : Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

-

ROM : Range Of Movement

-

EMG : Electromyography

-

TENS : Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

-

RTP/RTS : Return To Sports

-

NWB : No Weight-Bearing

-

WB : Weight-Bearing

-

PWB : Partial Weight-Bearing

-

FWB : Full Weight-Bearing

-

MAT : Meniscal Allograft Transplantation

-

LOE : Level of evidence

Ethics and consent

No need, systematic review and consensus Statements not involving human participants