INTRODUCTION

Pre-participation physical examinations are routinely completed as a medical evaluation for amateur and professional athletes of all ages. Typically, this examination assesses vital signs, vision, hearing, and the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems.1 Among college athletes, injuries occur at a rate of 13.8 injuries per 1000 athlete-exposures (AEs).2 Because of injury prevalence, risk factor identification has been the focus of many researchers from a variety of disciplines with the hope of identifying those most vulnerable to sustaining an injury.3,4

Considering the economic cost to society from musculoskeletal injuries, there has been a call for the medical community to shift the approach in the healthcare continuum from the treatment of these conditions towards prevention and earlier detection.5 Increased sport participation may lead to an increased incidence of musculoskeletal injury. Approximately 67% of former National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I athletes reported that they sustained a major injury during their athletic career, and 50% reported chronic injuries.6 Simon and Docherty suggest that collegiate athlete injuries that linger into adulthood possibly make participants less capable of staying active as they age resulting in a lowered health-related quality of life.7 Effectively managing the musculoskeletal health of student-athletes across their lifetime poses a distinct challenge.

The Functional Movement Screen (FMS™) was created to provide a time-efficient, systematic, movement-based inspection of the musculoskeletal system. The FMS™ is a seven-position physical test battery measuring whole body movements in a practical and systematic way, which is conducted by a trained health or fitness professional.8 The main purpose of the FMS™ is to establish a baseline before training or participation to identify dysfunctional movement patterns, asymmetry, and pain with activity.8,9 Because the FMS™ screens general movement patterns, the broad screening nature limits its ability to detect sport-specific considerations such as strength, power, or cardiovascular endurance.10 Previous research has suggested that the FMS™ is a reliable screen11,12 for detection of major physical limitations and asymmetries within movement patterns.8,9,13 Research supports that an athlete with a composite score ≤14 may experience a higher likelihood of injury compared to those with higher scores.14,15 The predictive ability of the FMS™ as a stand-alone tool has been debated by fitness and medical professionals. Rather than as a standalone injury-prediction tool, researchers recommends that best practice may be to use the FMS™ to assess movement quality along with consideration of other injury risk factors such as previous injuries, age, competitive level, and training load.14,16 An individual’s risk factors that may be modifiable with conservative interventions are commonly termed extrinsic or intrinsic factors. Extrinsic risk factors relate to the sport or the equipment. Intrinsic risk factors are the internal characteristics specific to the individual that may influence their susceptibility of injury.17

The FMS™ has been utilized by health and fitness professionals as a risk-assessment tool focused on identifying intrinsic risk factors.18,19 The FMS™ alone may support efforts to target movement deficits that could impede performance, increase vulnerability, or reflect inadequate recovery from a prior injury. When attempting to predict injury risk, research suggests that utilizing a multifactorial injury risk algorithm that includes pain with movement and additional factors such as injury history, FMS™ composite score, and Y-Balance Test-Lower Quarter scores. 20,21 Other studies have highlighted a need to consider additional variables such as blood work, fear levels, sport-specific considerations, and lifestyle factors.17,20–22 Implementing this comprehensive multi-component approach in community and school-based athletics poses a challenge in terms of feasibility. As the utilization of the FMS™ alone as a pre-participation movement screening tool has increased, this study aimed to explore the exposure of student-athletes to the FMS™.

To date, the authors have not encountered another study that delves into student-athletes perception of the significance of a pre-participation movement screening tool like the FMS™.

Understanding the perceived advantages and obstacles identified by student-athletes could provide valuable guidance for team management in implementing more effective pre-participation movement screening and conditioning plans. Eisner et al.23 investigated the perception of student-athletes relating to the importance of strength and conditioning. In their study, student-athletes reported positive responses recognizing the value and translational contribution to their overall athletic performance.23 Division 1 soccer student-athletes of both genders generally perceived that weight training was an important part of their training regimen.24 Value has been difficult to define and measure in healthcare research.25,26 In this study, the term value will be operationally defined as the athlete’s perception of benefit.

The purpose of this study was to assess athlete’s previous screen exposure, perception of screen value, and identify barriers in performing a pre-participation movement screen for college-aged student-athletes.

METHODS

Survey Development

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study that assessed the perception of pre-participation movement screens among student-athletes. An electronic survey was developed in Qualtrics. The survey was developed by the research team, whose collective experience included working with college-aged individuals, rehabilitation, and research. It was piloted with the Schreyer Institute for Teaching Excellence at Pennsylvania State University to gather feedback and make revisions aimed at improving readability. However, no formal data were collected to establish reliability or content validity. The survey contained 17-items which were represented in four sections including, 1) consent and demographics, 2) fear of injury and resistance to injury, 3) FMS™ exposure and perception of value, and 4) barriers to screen implementation. The survey can be found in Appendix A.

The first section consisted of five demographic questions relating to age, academic year, athletic team, campus, and gender identity. The second section involved three questions investigating the student athlete’s fear of injury and perception of injury resistance compared to their peers. The third section specifically looked at previous exposure to the FMS™ with a visual and brief description (Figure 1). This section had six questions directed at individual screen experience, perceived benefits off the FMS™, and individual willingness to participate in future screening initiatives. Participants were asked to rate their current individualized sport-specific conditioning program at their school. The final section included one question directed at student-athlete identification of primary barriers that may impede screen implementation.

Survey Deployment

Approximately 686 student-athletes from the commonwealth campus were contacted through email to participate in the online survey. These Commonwealth campuses included: Mont Alto, Behrend, Beaver, and Shenago. Participant recruitment was supported by commonwealth campus athletic directors and team coaches. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were student-athletes at the designated Commonwealth campuses, able to read and comprehend English, and were at least 18 years old. The investigators of this study did not have access to any other personal identification information. Participation in the survey was voluntary and all responses to the survey were anonymous.

Prior to beginning the survey, participants affirmed that they were 18 years of age or older and consented to their participation in the survey and study. Participants were excluded if they did not complete the required survey questions or selected the “I am not 18” or “I am 18 years of age or older, however, I do not consent to have my responses to this survey used for research purposes.” Responses to the online survey were prospectively collected during the academic year from September 2022 to April 2023. Approval from the institutional review board at the Pennsylvania State University were obtained prior to data collection for the descriptive survey study.

Statistical Analysis

The approximate number of student-athletes in the Mont Alto (n=130), Behrend (n=375), Beaver (n=137), and Shenago (n=44) commonwealth campuses accounted for a total of 686 student-athletes. A sample size of 248 participants was needed to ensure the responses reflected the views of the population with a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin for error. Descriptive statistics for nominal and ordinal data were summarized through frequencies and percentages and analyzed for differences with a one-way chi-square test. Cross tabulations and chi-square tests of independence were used to consider associates between identified variables. An alpha level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests. All data analyses were performed with Qualtrics and statistical tests were conducted with SPSS.

RESULTS

A total of 140 college-aged student-athletes responded to the online survey between September 2022 and April 2023, representing a response rate of 20%. Of these 140 surveys, 29 were excluded due to insufficient completion of questions beyond the demographic section. The remaining 111 surveys represented a final inclusion rate of 16% (n=111/686) that were used for data analysis. Since survey questions were not mandatory, there were inconsistencies in the responses, with a small number of participants either skipping questions or exiting the survey before completion. This explains the variations in sample sizes (n) reported across different analyses. Demographic information for the athlete’s age, academic cohort, sports team(s), campus, and preferred gender identity is displayed in Table 1.

Perceptions of Movement Screening Value

The student-athletes’ perceptions of movement screening value are summarized in Table 2. Sixty-nine percent (n=69/99) of student-athletes reported that the screen could aid in identification of injury vulnerability while 50% (n=50/100) reported that movement screening information could be used in programming to enhance athletic performance. Among responding student-athletes, 67% (n=68/99) and 75% (n=74/99) indicated that movement screening information could assist the coaching staff and athletic training team in managing musculoskeletal conditions in athletes, respectively.

Movement Screen Exposure

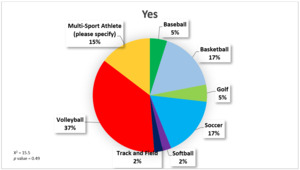

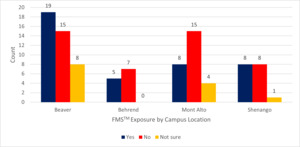

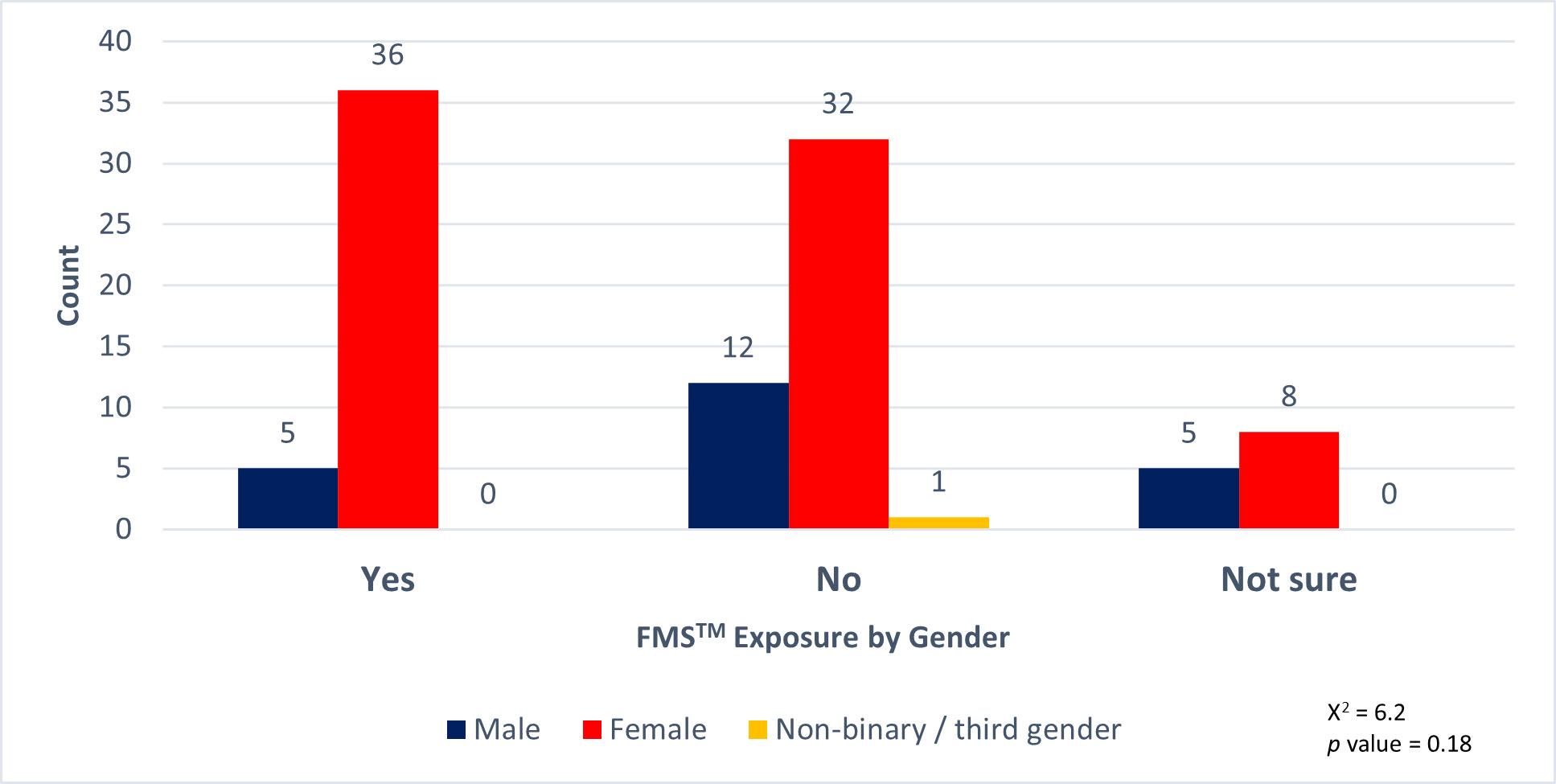

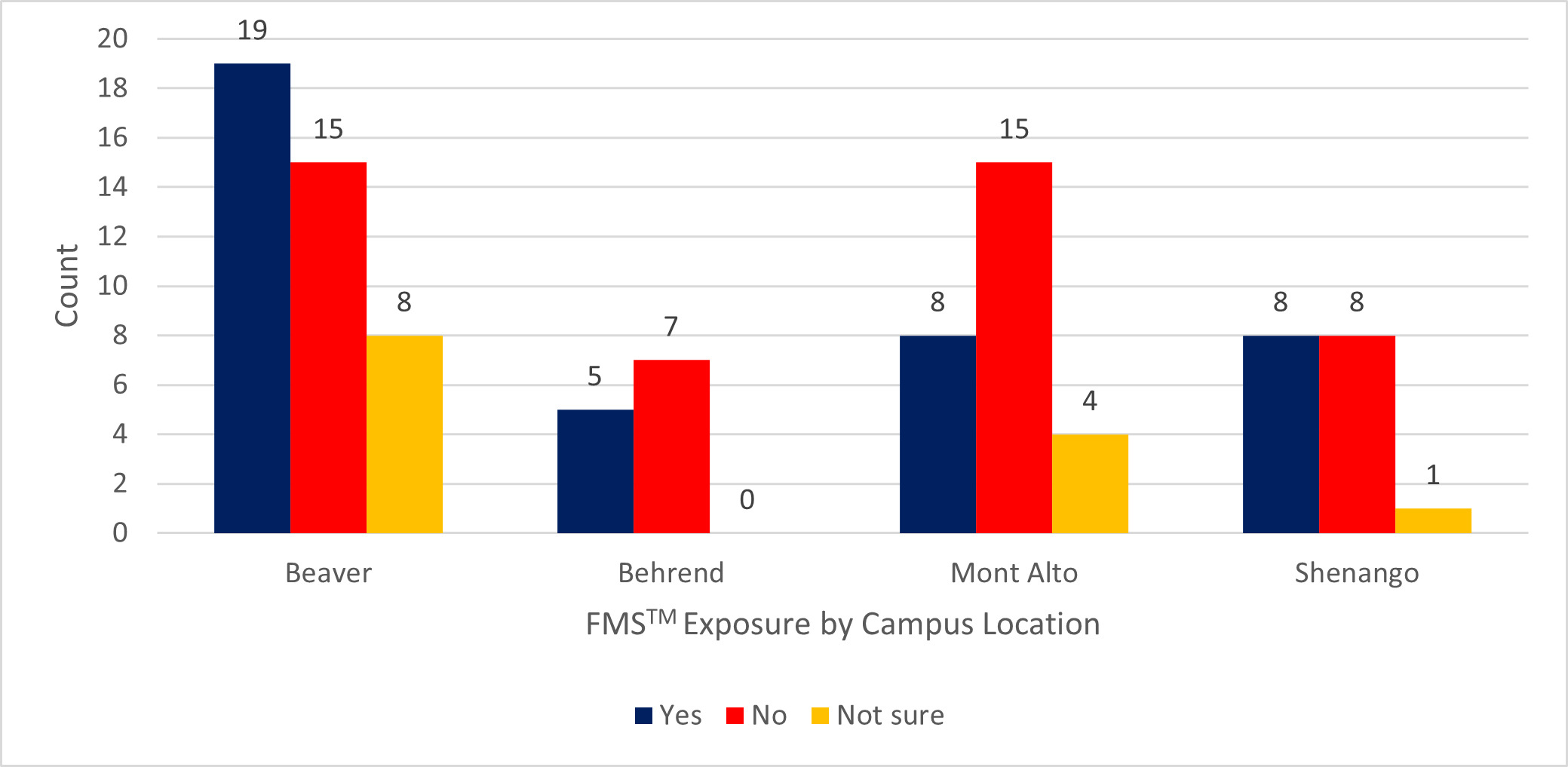

Among student-athletes who participated, only 41% (n=41/100) reported that they have been previously exposed to the FMS™ (Table 3). Chi Square analysis showed no significant relationship in previous FMS™ exposure within different sports teams (X2 =15.5, p-value = 0.49) (Figure 2). Furthermore, FMS™ exposure did not vary within identified genders (X2 = 6.2, p-value = 0.18), campus location (X2 = 6.5, p-value = 0.37), or respondent’s age (X2 =13.4, p-value = 0.34) (Figures 2-5).

Barriers to Movement Screening Implementation

The student-athletes identification of barriers to movement screening is displayed in Table 4. Lack of interest in pre-participation movement screening by the student-athletes was identified as the primary barrier to implementation (n=22/97) (Table 4). The second barrier identified was a lack of awareness that screens are available (n=16/97) (Table 4). Interestingly, 0 of 97 (0%) student-athletes reported that the time commitment to movement screening would be a major barrier to implementation. Seventy-five percent of student-athletes responding to the survey reported that they would participate in movement screen if it took less than 10 minutes to complete (Table 3). Only 9% (n=9/97) of respondents suggested that interruption of practice time would be a barrier and 23% (n=22/97) indicated that there were no barriers identified to interfere with screening implementation (Table 4).

Athlete Fear

Psychological readiness may be a valuable measure to include alongside other pre-participation metrics like the FMS™ and a medical-based physical. The authors of this study did find significant differences in the student-athletes self-reported injury vulnerability and their self-reported collegiate injury history over the last year (Figure 6). Statistically significant differences were identified between reported gender and fear of sustaining a sports-related injury. Male athletes tended to report lower fear levels (average 2.87/10) compared to female athletes (average 4.62/10).

DISCUSSION

The overarching purpose of this survey was to investigate the athlete’s exposure and perception of value and barriers with pre-participation movement screens. The results of this survey demonstrated less than half (41%) of collegiate-level athletes had previously been exposed to the FMS™ screen. From the viewpoint of college athletes, the implementation of movement screening could furnish valuable information to their coach and athletic trainer, aiding in addressing both injury prevention and performance enhancement objectives. The authors recognize that the notion of movement screening as a key component of global wellness and physical evaluation is not a novel concept. Hesitancy or unfamiliarity with movement screening among sports medicine providers, combined with time and resource constraints, may hinder widespread implementation. If student-athlete perceptions of movement screenings are not captured, there may be a missed opportunity to implement a proactive health measure while delivering a service that aligns with athletes’ interests and preferences.

Findings in this study support that most student-athletes reported a perceived benefit to themselves, their coach, and their athletic trainer (Table 2). Movement screening has demonstrated the ability to identify major musculoskeletal limitations, asymmetries, and pain. Teyhen et al. reported that greater number of musculoskeletal risk factors present during movement screening increased the likelihood of developing an overuse injury with a near perfect specificity.18 A risk that must be acknowledged is the over interpretation of movement screening scores without the consideration of broader wellness and athlete-specific training factors. Both the evidence and the student-athletes beliefs support the value of offering pre-participation movement screenings.

In this present study, 50% of student-athletes reported that the FMS™ could enhance their athletic performance (Table 2). A systematic review by Davies et al. reported that youth who score highly on the FMS™ also tend to have better scores for agility, running speed, strength, and cardiovascular endurance.10 Pfeifer et al. investigated FMS™ score and injury data throughout a sports season. Their findings revealed that dysfunctional movement as identified by the FMS™ may be related to increased odds of injury during the competitive season in youth athletes and the consideration of an individual’s movement within the context of their sport is necessary, as each sport and individual have unique characteristics.27

The secondary objective was to investigate if movement screening exposure varied by gender, location, sports, or age. No significant differences in responses were identified between athletes of different gender, sports, or ages in this study. There was no significant difference between geographic locations supporting that most student-athletes in the Commonwealth campus are experiencing similar accessibility to screening. Because the sample was limited to campuses within the state of Pennsylvania, the findings may not be generalizable to student-athletes from other geographic regions or institutional settings. The student-athletes were not asked to identify their home communities which may have included additional in-state or out-of-state geographical areas. No additional information as requested regarding when the athlete’s previous FMS™ was completed during their athletic career or how frequently in those who had been exposed to the screen.

The final objective was to explore the potential barriers identified by student-athletes regarding pre-participation movement screen implementation. Nearly a quarter of the participants indicated that there were no barriers identified that would interfere with screen implementation. This response implies that student-athletes believe implementation could be both feasible and successful within their athletic programs. The lack of interest by athletes was the primary barrier identified by student-athletes (23% of the sample). Future research comparing the perceptions of student-athletes in an environment with minimal screening exposure to those in an environment with regular movement screening exposure could provide valuable insights.

A comparable study that explored student-athletes perception of the value specific to the FMS™ does not exist, however Snyder et al. investigated high school football players’ perceptions of safety and support following a season of the use of a Helmet Impact Detection System. The findings from their study suggested that the use of instrumented helmets encouraged athletes’ feeling supported by coaches/administrators and their perceptions of safety which could impact their decision to engage in football.28 It would be reasonable to think that offering pro-active pre-participation movement screens could yield similar psychological benefits.

In the current study, previous exposure to the FMS™ screen did not statistically influence the student-athlete’s perception of injury resistance. It is important to consider how athletes may be influenced psychologically with the labeling of their overall injury risk or their movement screen score. Little research has investigated how screening impacts an athlete’s self-identity. However, stronger athlete identity has been identified as a risk factor for the development of depressive symptoms.29 As injury prevention initiatives are implemented, it would be valuable to investigated how this information influences an athlete’s identity. The identification of risk factors, especially in athletes, may have a psychological ripple effect, impacting how they perceive their bodies, their abilities, and ultimately their vulnerability to injury.30

It has been reported that athlete’s with greater self-reported fear were less active, had reduced performance with measured strength tests, and had an increased risk of suffering a second Anterior Cruciate Ligament injury in the 24 months after return to sport.21 Given the importance of student-athletes’ mental well-being, it is worth exploring how movement screening results may psychologically impact them—potentially offering positive reassurance about their readiness or, conversely, heightening fear of injury. These psychological responses can influence an athlete’s confidence, willingness to participate, adherence to training or rehabilitation programs, and overall performance. In this study, individuals who reported no injuries rated themselves as more resistant to injury compared to their peers. When athletes experienced mild or moderate injuries as defined by the author, they also indicated heightened vulnerability to injury compared to their peers.

Most student-athletes reported that movement screen information would be valuable to their coach (n=67/100). Podlog and Dionigi showed that the environment that the coach creates through their coaching behaviors can influence the satisfaction of an athlete’s basic needs, as defined by the Self-Determination Theory (autonomy, competency, and relatedness), and influence an athlete’s return from injury.31 A movement screen could enhance crucial communication among various members of an athlete’s management team, including a coach, athletic trainer, physical therapist, performance coach, and athletic director.

Subsequent research could be beneficial to delve deeper into the perception of value if screening is followed by an exercise plan to address results of the screen. Identifying barriers to pre-participation movement screening from various perspectives, such as those of the athletic director, athletic trainer, or coaches, could be advantageous. As professionals we seek opportunities to contribute to the management of musculoskeletal health across the lifespan, pinpointing sustainable outreach initiatives aimed at the student-athlete population may prove to be a significant area of focus.

Limitations

The survey was based on self-report which may have resulted in reporting bias by the responding student-athletes. Additionally, the survey used in this study was not formally assessed for validity or reliability, which may affect the accuracy and consistency of the findings and should be considered when interpreting the results. The data collection method made it challenging to control the Hawthorne Effect, potentially limiting external validity. There was a large gender disparity (75% identified as female) between respondents and an uneven team distribution which may have been influenced by their coaches’ support of the survey. Attrition in the survey responses was noted which may impact the accuracy of the study results. The selection bias of participants from the specific organization may have led to a limited regional perspective, posing a threat to both internal and external validity.

Additionally, the self-reporting accuracy of injury history and severity may vary between a student-athlete and a medical provider. Given the survey was distributed by email, technological restrictions such as access to a computer, or the Internet may have resulted in selection bias. The sampling may reflect the commonwealth campus level of athletics where resources are more limited and therefore may not reflect the same findings of more competitive athletic environments such as Division 1, 2, and/or 3.

CONCLUSION

The results of this research suggest that most student-athletes are receptive and willing to participate in pre-participation movement screening initiatives. Less than half of student-athletes had reported previous exposure to movement screening, like FMS™ testing, throughout their athletic careers. Few barriers were identified by student-athletes to inhibit successful program implementation. Therefore, pre-participation movement screening initiatives offered by health and fitness professionals most likely would be well received by student-athletes in their community.

Corresponding Author:

Amanda Snider

Penn State Mont Alto

309 Allied Health Building

1 Campus Drive

Mont Alto, PA 17237

Phone: 717-749-6235

Email: aks7451@psu.edu

Disclosure statement

The authors have no financial disclosures to report.