BACKGROUND

Patellar tendinopathy (PT) is commonly encountered in sport clinical practice,1 with a prevalence of 19.9% and an incidence of 7.5% in non-elite athletes.2 The prevalence among marathon runners is reported at 27.43%.3

The pathogenesis of tendinopathy remains incompletely understood, with various models attempting to explain the physiological processes and pain mechanisms involved.4–6 Diagnosis primarily relies on clinical assessment, including the patient’s history and the tendon’s response to loading.7,8 Imaging plays a limited role in diagnosis due to the lack of correlation between imaging findings and symptoms.7,9 Various treatment methods are used, including rest, activity modification, anti-inflammatory medication, injection therapies, taping, eccentric exercises, extra corporeal shock wave therapy, percutaneous electrolysis, and surgery.5,7,8 Eccentric loading remains the first-line of treatment and could be replaced or used in combination with heavy or moderate slow resistance and isometric exercises.10

The McKenzie Method of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT)11,12 is a classification-based system for musculoskeletal disorders. It categorizes patients into three mechanical syndromes — derangement, dysfunction, or postural syndrome — based on their response to repeated or sustained movements. The derangement syndrome is characterized by an internal displacement of articular tissue, leading to a disruption in the normal resting position of the affected joint surfaces.12 Despite this conceptual definition, the clinical presentation of derangement syndrome varies, and repeated movements often result in rapid and lasting changes in symptoms and mechanical baselines.12 Regarding extremities, the dysfunction syndrome is subcategorized into articular and contractile dysfunction.11 Articular dysfunction is determined by an intermittent pain consistently elicited at a restricted end-range of motion, with no rapid alteration in symptoms or range.11 On the other hand, contractile dysfunction is characterized by intermittent pain consistently provoked by stressing the musculotendinous unit.11

These syndromes are mutually exclusive allowing for individualized and specific treatment tailored to each group.11,12 The interrater reliability of the MDT system in identifying primary syndromes related to spinal issues appears to be acceptable, particularly when applied by therapists who have completed credentialed examination.13

In the MDT evaluation algorithm, spinal derangement may contribute to extremity complaints and should be screened before carrying out a full extremity examination.11,14 In a retrospective chart review, Hashimoto et al. reported that 44.6% of patients presenting with a primary complaint of non-acute knee pain were classified as having a spinal derangement. Interestingly, 28.6% of these individuals reported no concurrent low back pain (LBP).14 This proportion of knee issues associated with spinal derangement but without concurrent LBP was also highlighted in the study of Rosedale et al., where it was reported to be 25.0 %.15

This case report aims to illustrate the clinical reasoning process for a patient referred to physical therapy for patellar tendinopathy using the MDT system assessment.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 45-year old male was referred by his sports physician with a PT diagnosis in the right knee. The patient provided consent for the case report to be written with anonymized details.

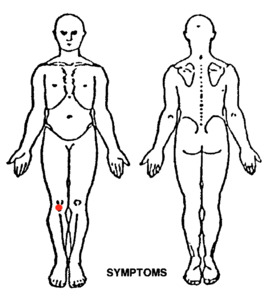

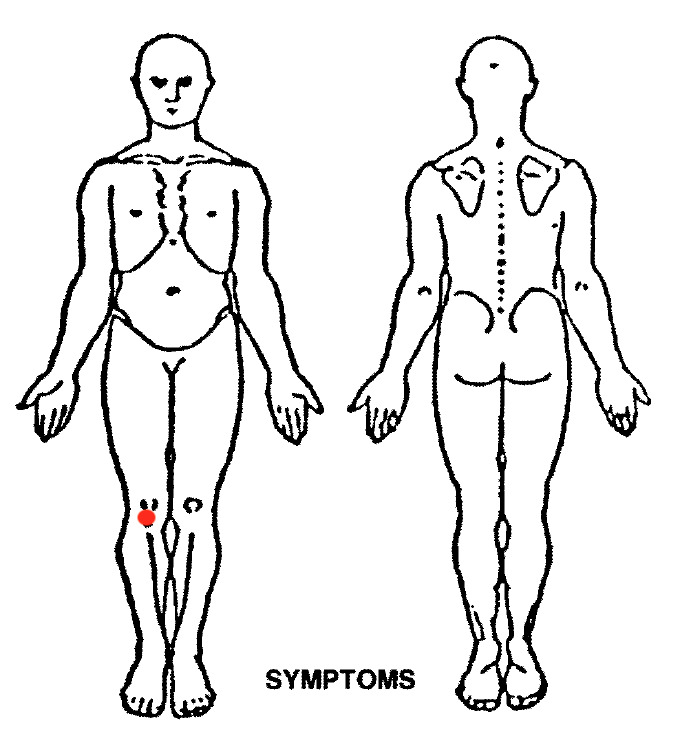

The subject of this case report worked as a fire security agent and was a voluntary fireman, which frequently required him to walk for long periods of time. He engaged in regular running activities and was preparing for a marathon, with a weekly training regimen involving 60 kilometers of running accompanied by lower limb strengthening exercises. The subject described experiencing pain at the inferior pole of the patella (Figure 1). He sought consultation due to pain with his primary objective being to complete his marathon training regimen effectively and to participate in the upcoming marathon scheduled for one month later.

The patient reported a history of recurrent episodes of anterior knee pain over the prior decade with the current episode beginning a year prior to consultation. Additionally, he experienced intermittent LBP exacerbated by heavy lifting as well as left Achilles tendon pain which had been previously managed with ice application, shockwave therapy, and platelet-rich plasma injections.

The knee symptoms were intermittent and exacerbated by sitting for prolonged periods, walking after prolonged sitting, and squatting. Pain was particularly noticeable in the morning after running sessions, during knee flexion, and while running, particularly during long-distance and interval training. Symptoms were alleviated by massage, wearing a patellar tendon strap, and maintaining the knee in extension. Continued knee use exacerbated the pain, and he experienced disrupted sleep when lying prone. He had not received any prior treatment for the knee issue.

The patient’s overall health was good, and he was not taking any medications. Knee magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and arthrograms did not reveal any significant findings, while a lumbar spine MRI indicated the presence of L5-S1 discopathy.

OUTCOME ASSESSMENTS

Baseline assessments included the Victoria Institute of Sport Assessment score for PT (VISA-P),16 which was recorded at 57/100, and the Numeric Pain Rating Score17 (NPRS) ranging from 0 to 10 (0, no pain; 10, pain as bad as it could be), with scores of 4/10 at rest after sport and 7/10 during physical activities. The VISA-P is a self-administered questionnaire designed to assess symptoms of PT, functional ability, and sports participation (see Appendix). It comprises eight questions, with seven responses scaled from 0 to 10 and one response scaled from 0 to 30. The theoretical minimum score is 0, while asymptomatic individuals are assigned a maximum score of 100.

Scores below 80 are typically indicative of PT, as demonstrated by previous study,18,19 although false positives have been observed in asymptomatic individuals when the VISA-P is used as standalone measure.19 The VISA-P is a valid and reliable tool for assessing the severity of symptoms in patients with PT,16 a validity that extends to the French version as well.20

CLINICAL IMPRESSION #1

Following the initial interview, several aspects of the patient’s history suggest a preliminary classification of contractile dysfunction, which is the MDT equivalent term for tendinopathy.11

PT is a common overuse injury, particularly prevalent among marathon runners.21 The primary risk factors for PT include previous injury, intense training, and high weekly mileage. Running more than 60 km/week poses a significantly higher risk of injury, with a relative risk of 2.88.22 This patient exhibited all three of these risk factors.

The location and onset of pain align with typical features of PT. Pain aggravated by quadriceps loading, discomfort with prolonged sitting and squatting, as well as pain following energy-storage activities, are indicative of PT but also overlap with symptoms of patellofemoral pain.8

The use of patellar tendon strap aims to alleviate tensile stress on the tendon and has been shown to reduce pain during physical activity.23 Although the patient’s knee imaging did not reveal specific findings related to tendinopathy or other alternative diagnoses, MRI is recommended for suspected tendinopathy,9,24 as it offers excellent reproducibility.9 However, there is often a poor correlation between the presence of pain and MRI findings.8,9

Despite these features, the potential involvement of the spine in the patient’s complaint could not be ruled out. The patient has a history of LBP exacerbated by heavy lifting and a lumbar MRI revealed discopathy. These factors prompted consideration of the spine in the MDT assessment algorithm to rule out potential spinal implication in extremity disorders.11,15

EXAMINATION

The patient reported no pain while standing or at rest. Functional tests relevant to the patient’s activities were conducted as part of the baseline assessment.25 Knee pain was elicited during a single-leg decline squat (Figure 2), three single-leg hops, and five step-downs (Figure 3). These tests were used to assess the response of the patellar tendon to loading.7,8,25 The single-leg decline squat was used as a clinical tool for assessing patellar tendinopathy, with the decline angle increasing stress on the patellar tendon.26 The reliability is good to excellent for counting the number of repetitions.27 Resisted knee extension did not elicit pain, and the knee exhibited full and painless range of motion.

As the patient described previous LBP, a comprehensive lumbar examination was conducted. Initial baseline movement assessments revealed minimal loss in flexion and extension, with no loss in sidegliding, and no pain reported at end range of movement. To further evaluate symptomatic response during movement, therapist- applied overpressure was employed. Lumbar pain was elicited during flexion overpressure, while none was reported in other movements. Additionally, a passive straight leg raise (PSLR) was performed bilaterally to assess the mechanosensitivity of the sciatic nerve and potential spinal involvement in Achilles tendon pain.28–31 Right PSLR at 60° produced back pain, whereas left PSLR was painless and full. No further baseline examinations were conducted at this stage.

Repeated movement tests were used to assess symptomatic and mechanical responses without the patient wearing a patellar tendon strap. No back or knee pain was reported during these tests. Repeated extension in standing was initially performed without symptom exacerbation. Subsequently, repeated extension in lying position was conducted which did not elicit pain but improved lumbar flexion during overpressure, right PSLR, single-leg decline squat, single-leg hops, and step-down, with 3, 10 and 15 repetitions, respectively. To confirm that extension was the appropriate direction of movement, flexion in lying position was attempted, which did not induce lumbar pain but reverted back all symptoms to initial baseline. Therefore, no further tests were applied.

Based on these findings, a provisional classification of lumbar derangement was established, with a potential directional preference (DP) in extension. The DP refers to the specific direction of movement that alleviates symptoms and/or improves mechanics.12

CLINICAL IMPRESSION #2

Based on the response to repeated movements, a provisional classification of lumbar derangement was established. Contractile dysfunction is characterized by pain elicited upon loading the musculotendinous unit.8 For this patient, pain was reproduced during loading of the tendon with the single-leg decline squat, single-leg hops and step-down exercises. However, the patient’s history of LBP, minimal lumbar movement loss, lumbar pain induced by clinician-applied overpressure during flexion, and positive right PSLR suggested a potential spinal issue and warranted consideration for referral to the knee and ankle.12 Given that lumbar loading resulted in rapid and sustained improvement of knee baselines, directly aligned with the patient’s goals, lumbar spine derangement classification under the MDT system was deemed appropriate. This classification would need to be confirmed during subsequent appointments by observing reduced pain during daily activities, improved NPS, and possible pain centralization. Centralization refers to the progressive abolition of distal pain originating from the spine in a distal-to-proximal direction.12,32 Additionally, improvement in knee baseline functional testing during the session, such as the single-leg hop and decline squat tests, would further support a lumbar origin for the patient’s knee symptoms.

INTERVENTION

Initial Session

The repeated movements used during the assessment, a hallmark of MDT evaluation, were also incorporated into the treatment program. Repeated extension in lying resulted in significant improvement in mechanical and symptomatic baselines, both for the knee and the lumbar, confirming the presence of lumbar derangement.

Based on his response to the self-treatment, the patient was instructed to perform 10 repetitions of extension in lying 4-5 times daily. Additionally, he was educated to maintain proper lordosis while sitting and was encouraged to perform the exercise prior to running or as necessary. Clear instructions were provided to discontinue the exercise if symptoms were worsened or any adverse reaction occurred.

Session 2

Seven days later, the patient reported consistent adherence to his exercise regimen and demonstrated correct technique and posture correction while sitting. He also reported a significant reduction in pain during sitting and walking, although he still experienced discomfort rated at 4/10 during physical activities and 2/10 on the day following running sessions.

A reassessment of previously established back and right knee baselines were performed. Right PSLR elicited no pain and demonstrated full range of motion while flexion in standing with overpressure did not induce back pain. Single-leg hops and step-down were also pain-free, whereas the single-leg decline squat showed improvement but persisted as painful with five repetitions.

The patient performed 4 sets of 10 repetitions of extension in lying with sustained positions and exhaled during the last three or four movements of each set to apply overpressure.12 This treatment led to an increase in the number of repetition to 10 during the single-leg decline squat before experiencing pain. Despite ongoing discomfort, the patient was still able to improve his symptoms with self-treatment and progression of force application.

The observed improvements in both reported symptoms and clinical examination findings for the knee and the back supported the classification of lumbar derangement, with a DP in extension. The patient was advised to maintain his exercise routine with added overpressure as this contributed to further improvement in his baseline conditions.

Session 3

During the follow-up appointment four days later, the patient continued to demonstrate good adherence to his exercise regimen and exhibited correct technique. However, he reported a plateau in his improvement, with no change in pain level during activities. The single-leg decline squat remained painful with 10 repetitions, while other baseline tests did not elicit pain.

According to the MDT principles, a progression of forces was implemented as the patient’s mechanical and symptomatic presentation did not change.12 Extension in lying with clinician overpressure was performed (Figure 4).

The clinician crossed his arms, placed his heels of hypothenar eminences on the transverse processes of the same lumbar level, with hands at 90° to each other. The clinician applied perpendicular force to the movement, with gentle and symmetrical pressure while the patient performed extension in lying. The pressure was maintained during the movement as the clinician moved with the patient and released at starting position.12 This procedure successfully alleviated the pain experienced during the single-leg decline squat confirming the classification of lumbar derangement with DP in extension. Thus, the patient was asked to replicate this movement at home using a towel placed across his pelvis, with his wife standing on either end of the towel, mimicking the clinician’s overpressure technique (Figure 5).12

Session 4

Ten days later, the patient reported consistent adherence to the prescribed exercise regimen. He noted a complete absence of pain over the prior seven days during long-distance running and interval training, as well as the following day.

Upon reevaluation, initial knee and back baselines were conducted and found to be pain-free. The VISA-P score was 99/100, indicating no functional or sport limitation. However, his Achilles tendon pain remained unchanged and was addressed separately.

To ensure the stability of the reduction in derangement, the patient was put through repeated flexion, following a progression of forces from self-overpressure to clinician overpressure.12 No symptoms were reported during these tests, confirming the stability of the reduction.

Management of derangement syndrome typically involves four steps: (1) reduction of the derangement, (2) maintenance of the reduction, (3) recovery of function, and (4) prophylaxis.

In this case, the derangement syndrome was confirmed by the rapid and sustained improvement in knee and back baselines measurements.

The confirmation of derangement reduction was evident through the absence of pain during the full single-leg squat and full extension range of motion. Recovery of function was achieved through the repetition of flexion following the force progression, accompanied by the absence of knee pain during and after running sessions. Prophylaxis measures were addressed by instructing the patient to continue performing the prescribed exercise as needed to maintain his progress leading up to the marathon.

Followed the marathon, the patient contacted the clinic to report successful completion without experiencing knee pain. He was advised to continue the exercises as necessary for ongoing maintenance.

Follow-up

Six months after discharge, the patient was contacted and reported being able to run without experiencing any pain, performing lumbar extension routinely. Additionally, he was preparing to participate in another marathon. His verbal report indicated a perfect score of 100/100 on the VISA-P assessment.

DISCUSSION

Patients with knee complaints are frequently encountered in healthcare settings,1 with PT being one of the most common prevalent conditions, particularly among long-distance runners.3,33 Prognosis for PT is usually favorable, with return to sport occurring within 20 to 90 days depending on symptom severity.34 However, PT often presents with recurrent symptoms in patients.35 Numerous conservative treatments exist, including exercises targeting pain and quadriceps strengthening.7,8,10

In this case, the patient’s history and examination suggested a diagnosis of tendinopathy, with potential effectiveness of specific interventions. Interestingly, the patient reported previous episodes of LBP, prompting screening of the spine while assessing the extremities to the MDT principles.11 Application of reductive mechanical forces to the lumbar spine resulted in rapid and lasting resolution of knee symptoms, indicating the lumbar spine as a potential source of symptoms.

While a previous case report using MDT has described cervical spine implication in shoulder complaints,36 to the authors’ knowledge, no case reports have described lumbar spine involvement in knee disorders. The etiology behind knee pain originating from the lumbar spine remains unclear. Hashimoto et al.14 provide three potential hypotheses. First, lumbar repeated movements would change the dynamic alignment of the spine, which would contribute to an altered mechanical loading to the knee.37,38 Second, the L4 root contributes to the pain experienced by patients with knee osteoarthritis,14 with innervation of the anterior knee by the infrapatellar branches of the saphenous nerve.39 This presentation could reinforce the hypothesis of the lumbar spine as a primary source of knee pain. The third hypothesis would be that mechanical loading to the spine would have a hypoalgesic effect on the knee, involving a pain inhibition system mediated by the central nervous system.40 However, limited and conflicting evidence exist on sensitization of the nervous system in patellar tendinopathy.6,41,42

Limitations of this case report include those typical of a case report, with non-generalizable results and cause and effect can not be presumed. Additional limitations were follow-ups done at distance from the initial assessment and by phone. However, due to the chronicity of symptoms and the rapid changes in the initial evaluation, it could be argued that clinical intervention and not natural history could have impacted the outcome in this subject.

CONCLUSION

Through a comprehensive MDT examination, the subject of this case report was ultimately diagnosed with a lumbar derangement, despite many features indicating treatment for patellar tendinopathy. The implementation of self-management strategies yielded a rapid alleviation of symptoms and an enhancement in both function and pain levels at the knee. Furthermore, the case report illustrates the utility of MDT assessment in distinguishing between the knee and the lumbar spine-related symptoms. Future research endeavours should focus on identifying predictors of spinal implication in extremity disorders and assessing their validity to detect this patient subgroup.

Disclosures

No funding was provided for the preparation of this manuscript and the authors declare no conflicts of interest.