DEFINITION, ETIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT

Proximal hamstring tendinopathy (PHT) can occur in active and sedentary people and presents clinically as localized lower buttock pain with activities including prolonged and hard surface sitting, squatting, and walking uphill or running.1–3 There are sparse data on the prevalence of PHT, although it is reported as a common3,4 and disabling4,5 condition in the athletic population.

Overloading or underloading can result in tendinopathy. The tendinopathy continuum model6 describes tendon pathology as a staged process based on structural disorganization. Acute overload can result in reactive tendinopathy,6 with tendon swelling secondary to increased large proteoglycan content, but intact collagen structure. Continued chronic overloading can lead to ‘disrepair’ or ‘degenerative’6 tendinopathies where the collagen and tendon matrix is disrupted. In addition to structural changes, there is an interplay between pain and function in tendinopathy.7

The principal function of tendons appears to be transmission of tensile loads, however compressive loads can also contribute to adaptive changes in the tendon matrix and tendinopathy.6 In PHT, compressive load occurs at the ischial tuberosity through activities involving higher ranges of hip flexion, including lunging, kicking, squatting and hamstring stretching, or with direct compression in sitting. Activities involving compressive load are common aggravating factors in PHT.1,3 The location of tendinopathic change in PHT in surgical8 and imaging9 studies is adjacent to the PHT insertion at the ischial tuberosity, supporting the hypothesis of compressive forces as a fundamental factor in the development of this condition.

A recent systematic review of interventions for PHT reported insufficient evidence to recommend one intervention over another.10 Shockwave therapy has been shown to be effective for PHT when compared to a conservative intervention including three weeks of exercise,2 however the exercise approach in this trial was incongruent with expert recommendations.11 The most commonly recommended treatment for PHT by experts is education and exercise.11 The rationale is that educating regarding load management including monitoring for latent pain response facilitates symptom reduction and effective exercise progression with resultant functional improvement.12 Exercise for PHT aims to restore kinetic chain function and loading capacity of the hamstring complex.13

The purpose of this commentary is to outline an education and exercise program developed for treating PHT utilizing principles successful in clinical trials for other tendinopathies adapted to the specific anatomical and biomechanical considerations of the proximal hamstring complex. The treatment protocol is currently being followed in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to compare the exercise program (‘PHYSIOTHERAPY’) with extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT, ‘SHOCKWAVE’) (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry #ACTRN12620001243909).14

PHYSIOTHERAPY INTERVENTION: OVERVIEW

The physiotherapy intervention (Table 1) is centered around a multi-stage, progressive loading, individualized exercise program incorporating hamstring and kinetic chain exercises. A significant component of the individualization is through matching exercises to each patient’s sporting and occupational goals. The intervention addresses known and hypothesized mechanisms of tendinopathy and previously published guidelines for treatment of PHT3,15 and other lower limb tendinopathies.16 Progressive loading is recommended for PHT3,15,17 although there are limited data demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach compared to other interventions. The intervention was developed by the lead author in conjunction with the research team that includes a clinical and research expert in tendinopathy (JC).

There are multiple mechanisms by which exercise may result in clinical improvement, although the extent to which each contribute is uncertain.18 They include improved hamstring voluntary activation (via enhanced corticospinal excitability and reduced cortical inhibition),19–21 improvement in mechanical properties such as muscle-tendon unit stiffness22,23 and tendon modulus,24 increased matrix protein production,25 neurochemical interactions related to glycosaminoglycans and fluid dynamics,23 restoration of hamstring complex and kinetic chain load capacity,17,26–28 improved coordination of stretch shortening cycle,29,30 increased cross sectional area of the tendon,24 and structural changes within the tendon.31 The therapist-participant ‘working alliance’,32 placebo effects, natural history of the condition, and education may also contribute to any improvements.33

Standardized education

Standardized information sheets are provided to participants covering diagnosis, monitoring pain, managing compression, and management of high and low tendon loads (Supplemental File 1). The principles provided in the information sheets are applied to all sporting and occupational demands. These information sheets are provided in sessions one and two of the intervention, with an additional information sheet on discharge advice provided at the sixth and final session. Treating physiotherapists are directed to refer participants to these information sheets to answer questions where possible, and participants are encouraged to review the information sheets regularly. Education has been shown to be effective in treatment of other tendinopathies.33

Diagnosis: Provision of a diagnosis for what can be a challenging condition to diagnose,3,34 along with reassurance that function and pain are likely to improve with treatment, may provide reassurance for the participant.35

Monitoring pain: Some hamstring tendon pain will be accepted consistent with successful approaches in other tendinopathies,36,37 with <4/10 the most commonly used threshold.

Pain beyond these levels trigger modification of prescribed exercise by reducing one or more variables regarding weight, load, repetitions and/or hip flexion angle, or temporarily stopping an exercise within a stage. The approach to modifying exercises in the presence of higher pain levels will vary with the specific stages of treatment (Table 1). For example, in Stage 1 higher initial pain levels are tolerated on the first two repetitions due to the expected analgesic effect of the exercise, while in Stage 5 a lower threshold is used as these exercises are thought to be more provocative in tendinopathy and the risk of a flare up of pain is greater.3

Latent pain onset after completion of activity is common in tendinopathy and thought to be an indication of unhelpful loading,28 although the underpinning mechanisms for this response are uncertain. An increase in pain with repeatable tasks of ≤2/10 is acceptable within 24 hours after undertaking the exercise program, however with increased pain of ≥3/10 persisting beyond this timeframe, exercise modification is prescribed as described above.

Treating physiotherapists may be required to emphasise the message of “hurt versus harm” (i.e. that low pain levels during activity are not dangerous or indicative of damage to the tendon) and reiterate that latent (12-24 hours) pain with repeatable activities is the best indicator of tolerance to activity.28 This message is emphasized to a greater extent with participants with a high (>50) baseline score on the fear avoidance component (question 9) of the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire Short Form (ÖMPSQ-SF).38 The ÖMPSQ-SF is a measure of psychosocial risk factors39,40 and fear avoidance beliefs appear to be associated with increased disability41 and poorer outcome42 in other tendinopathy trials.

Compression: Participants are advised to minimize compression of the proximal hamstring tendons. Compression in PHT occurs with activities such as sitting, hamstring stretching, or activities involving hip flexion (deep squatting, lunging). Practically, a reduction in compressive loads with sitting is advised through minimizing prolonged and hard surface sitting, and/or use of a soft or pressure dispersing seat cushion. It is thought that tendinopathic tendons have reduced tolerance to compressive load due to swelling of the tendon (via deposition of aggrecan and it’s by-products)43 and presence of collagen type that has poor tolerance of compressive loads.44 A graded reintroduction of compressive loads will be undertaken consistent with clinical expert opinion3,17,45 in Stage 4 of the physiotherapy intervention.

Key components of the exercise program

Graded hamstring strengthening: Hamstring strengthening is provided through isometric (Stage 1) and isotonic (Stage 2) exercises.

Isometric exercise is commenced on a dosage and intensity sufficient to allow quality contraction for the entire repetition duration (Table 1), and is progressed by reducing leg support, progressing to single leg, or increasing repetition duration as the ability to maintain a quality contraction improves over time, as assessed during treatment sessions.

Isotonic exercise dosage is commenced on lower intensity and progressed to higher intensity exercises (Table 1). Prescription for isotonic exercises is progressed by adding repetitions, weight or resistance as strength improves, or as pain levels reduce.

Auditory cuing: Use of an external auditory cue (e.g., metronome app on smart phone) is utilized to promote improved voluntary hamstring activation in all stages (Stages 1, 2 and 4) that directly load the hamstring.46–48

Contralateral training: Exercises are performed on both legs (individually) at all stages, except in situations where single leg exercise is unable to be performed due to pain or strength limitations. Motor and sensory deficits are present bilaterally in unilateral tendinopathies,49 suggesting a central nervous system influence. Unilateral strength training results in a contralateral strength increases (the “cross education” phenomenon), likely due to centrally mediated changes in motor control.50 Resistance varies between legs to elicit the desired level of load and/or to control pain levels.

Restoration of kinetic chain function through agonist strengthening and lumbopelvic motor control: The intervention includes strengthening exercises for the agonist muscles to the hamstrings. People with PHT often have deficits in gluteus maximus and triceps surae and adductor strength11 and these muscle groups are targeted. Restoration of agonist strength deficits is intended to improve power and load distribution and is recommended for treatment of PHT3,15,17 and other lower limb tendinopathies28 however to date has not been investigated in an RCT setting. Control of lumbo-pelvic posture and movement is incorporated into all stages at treating physiotherapist discretion, based on visual observation during strength training and/or functional activities such as running and walking. Unhelpful posture and/or movement of the lumbar spine or pelvis in any plane thought to be relevant to the PHT is incorporated into the intervention.

Individualization: The intervention is individualized based on treating physiotherapist discretion based on several factors. Participants are provided with an exercise program specific to their goals (self-identified during the first treatment session) based on important activities of daily living (ADL). Rate of progression through the stages varies based on level of deconditioning, severity of clinical presentation, adherence, and individual response to prescribed exercise. Stage 5 is only undertaken by participants who are reasoned to have high energy storage and release demands. Lumbopelvic motor control training is another factor where the intervention is individualised.

STAGES OF THE EXERCISE PROGRAM

An overview of the five stages of the intervention (Table 1) and the progression through them (Figure 1) are provided; detailed flow charts for individual stages are provided in the supporting information.

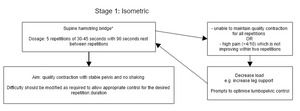

Stage 1: Isometric

The aims of Stage 1 are to decrease pain if high pain levels are present, to allow for ‘warming up’ prior to subsequent exercises, and as a method of reassuring participants that controlled loading of the hamstring complex is safe. All participants will begin at this stage and it can be discontinued by the treating physiotherapist if there is no clinical rationale to continue, for example if full pain-free function has been regained and ‘maintenance’ strength exercises are being utilized.

The effect of isometric exercise has been investigated on a range of tendinopathies. The initial study on isometric exercise in patellar tendinopathy showed immediate improvements in pain on tendon loading and improved strength which was sustained for 45 minutes after the loading bolus.20 A potential mechanism for these changes are enhanced corticospinal excitability and reduced cortical inhibition altering voluntary muscle activation.20 Further studies on isometric exercise in other tendinopathies have shown mixed results,51–60 however there are methodological considerations around diagnosis and measurement that may contribute to these findings. The effect of isometric exercise has not been measured on PHT. The use of isometric exercise in early management of PHT is recommended by clinical experts and in clinical commentaries.3,11,15 An RCT is currently underway investigating the effect of isometric exercise on pain and strength in PHT.61

A supine hamstring bridge (Figure 3) is used for Stage 1. This variation of isometric exercise is likely to be better tolerated across the spectrum of PHT presentations due to its ease of implementation, and adjustability. Other exercise options are available if there are limitations (e.g., back pain) to performing the hamstring bridge. A dosage similar to other successful isometric trials20,57 on tendinopathy is utilized, with participants asked to complete five repetitions of 30-45 seconds of isometric contraction. The exercise is made more challenging by progressing from double to single leg, by increasing weight or by reducing leg support as the participant can maintain a quality contraction for all repetitions for 45 seconds. Shaking of the leg is not permitted and lumbopelvic control (lateral and sagittal control with avoidance of excessive anterior pelvic tilt due to its impact on PHT) is emphasized. Higher pain levels for up to two repetitions of this exercise are permitted to allow time for the analgesic effect however if pain levels of >4/10 persist beyond this, the exercise will be modified, generally by reducing the load but potentially by changing prompts for optimizing lumbopelvic control.

Stage 2: Isotonic strength

The aim of Stage 2 is to increase capacity and motor control of the hamstring complex. Reduced hamstring strength and hamstring muscle atrophy is commonly seen in PHT.11 Treatment of other lower limb tendinopathies with graded strengthening interventions aimed at building capacity have demonstrated improvement in pain, disability and function.37,62–74

A supine hamstring bridge is again used as the preferred exercise for Stage 2 (Table 1). This stage is undertaken three times per week (or every second day) initially, reducing to twice weekly when strength is equal to or greater than the unaffected side, noting that this may take three to six months or more to achieve in longstanding cases of PHT.17

Stage 2 is commenced after Stage 1 and participants have demonstrated the ability to perform the exercise within the parameters of the stage, generally at session one or two. Exercise loads are closely monitored and progressed in Stage 2 as heavy75 and progressive76 strength exercises appear more beneficial in stimulating positive adaptive changes22 and improving clinical outcome in tendinopathy. Therapist discretion is used for exact dosages however participants will generally commence on a higher number of repetitions at a lower relative intensity (e.g. 2-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions) before reducing the number of repetitions (and increasing the intensity) in later weeks, with a typical late stage prescription being 4-5 sets of 6-8 repetitions. This approach is undertaken to assist with emphasising correct technique, reduce the risk of any aggravation of symptoms or significant delayed onset muscle soreness that will delay progress or discourage further strength training and is consistent with a successful intervention for treating Achilles tendinopathy.36 The intensity for this stage is aimed at a level where the participant could not complete an additional set with the appropriate technique, however if a participant has a limited resistance training history and/or ongoing high pain levels, the physiotherapist will be advised to have a cautious approach and keep the intensity of exercises lower. Physiotherapists will closely monitor the latent pain response from exercise and will coach the participants to do this via use of information sheets – if there is significant (>2/10) increase in pain with a repeatable task for greater than 24 hours. In this situation the physiotherapist will reduce the intensity of the prescribed exercise.

Stage 3 – Kinetic chain

The aim of Stage 3 is to address capacity, function, and motor control of the kinetic chain. Assessment and treatment of lower limb and lumbopelvic kinetic chain deficits is recommended for treatment of lower limb tendinopathies,16,28 and triceps surae and gluteus maximus strength are commonly reduced in PHT.11,77 Adequate kinetic chain function is important for development of power, absorption and distribution of loading forces and normalising running technique.28 Examples include a runner with a history of ankle sprain and subsequent reduced triceps surae function, or a runner with reduced hip extension function following an episode of low back pain, both of which could result in increased load through the hamstring complex.

All participants undertake calf and hip extension strength exercises. Treating physiotherapists can also prescribe quadricep strengthening if they determine there are strength deficits based on objective strength testing (e.g., single leg knee extension). Variations of hip thruster (Figure 6), calf raise, step up and leg extension exercises are used in this stage.

Lumbopelvic control retraining exercises are included based on individual participant assessment by the treating practitioner. The physiotherapist assesses the participant performing functional tasks (squatting, single leg stance, walking, running), observing for features of reduced lateral pelvic control or excessive anterior tilt. Features of reduced lateral pelvic control include a positive Trendelenburg sign78 or ipsilateral trunk lateral flexion,79 excessive anterior tilt is contextualised within the lumbo-pelvic complex, e.g. if there is increased lumbar lordosis it would strengthen the hypothesis of excessive anterior pelvic tilt. If these features are present, lumbopelvic control retraining exercises (Figure 6) are prescribed using a ‘motor control’ approach, with an emphasis on performing only high-quality repetitions with acceptable lumbo-pelvic and trunk control.

Stage 3 is commenced once Stages 1 and 2 exercises have commenced, generally in the second or third session. Participants progress from an ‘endurance’ (2 sets of up to 20 repetitions) to ‘strength’ (3 sets of 6-10 repetitions) dosage for calf and hip extension exercises, after meeting set milestones. Quadricep exercise prescription is ‘strength’ dosage only as quadricep strength is less likely to be severely impacted with PHT and these exercises are unlikely to cause aggravation of PHT symptoms so can be commenced at a higher intensity.

Stage 4 – Compressive load

The aim of Stage 4 is to assess and progress the tolerance of the hamstring tendon complex for compressive load. Graded reintroduction of compressive forces in exercise-based interventions is recommended for PHT3,45 and other lower limb tendinopathies.13,44,80,81 Stage 4 is ceased when the individual requirements of compressive load are met, as the compressive load is thereafter met by sporting/occupational activity.

Stage 4 commences once the participant has demonstrated tolerance of Stage 2 exercises for at least two weeks but will often be commenced at a later stage if significant strength deficits are present. A modified deadlift (Figure 8) is used to reintroduce compression, with participants commencing at or close to their maximum functionally required weight and progressing by adding hip joint flexion and repetitions progressed once initial tolerances are demonstrated. Other options (lunge or elevated bridge) can be used if a deadlift cannot be performed (e.g., due to low back pain). The nature and intensity of compressive load training is determined by the ADL goals of the participant and progressed until the demands of these activities are met, at which time Stage 4 exercises are ceased. For example, an athlete required to pick a ball of the ground during competition (e.g., Australian football) require more hip flexion and tolerance to compressive load than a distance runner. Recreational or occupational exposure to hip flexion (e.g., gardening, manual labouring) are also considered. For many participants, this stage does not elicit high levels of fatigue as their maximum functionally required weight is relatively low, e.g., lifting a child, or household items from a low height. Participants who wish to return to activities such as deadlifting require a higher weight.

Stage 5 – Energy storage and release

The aims of Stage 5 are to increase the energy storage and release capacity of the hamstring and lower limb complex, through biological adaptions including increased tendon stiffness. Pain related to tendinopathy can inhibit the ability of the tendon to store and release energy, affecting normal function and optimal performance.25 Stage 5 also serves to assess for return to modified training for athletes in high energy storage and release demand sports such as field or court sports.

Only participants with a requirement for high energy storage and release demands in their sport or occupation complete this stage. Running athletes (not field or court sports) where loads (speed, distance) can be more easily quantified and energy storage and release demends are low generally skip this stage and instead undertake a graded return to normal run training. Stage 5 (Figure 9) is commenced once strength deficits on the affected limb are assessed to be negligible, and Stages 2 and 4 are well tolerated. It is acknowledged that reaching this stage may take greater than the 12 weeks for individuals with significant deconditioning upon presentation.

Exercises including split squats are used in stage 5 although exercises in this stage can be tailored to individual demands; sport-specific exercises could include modified lunge to simulate a tennis volley or low backhand or a ‘hamstring scoop’ exercise to simulate picking up a ball off the ground in football.

A lower pain threshold (≤2/10) is used for Stage 5, as energy release and storage demands provide higher loads to the tendon and are thought to have a higher risk of causing a flare up of pain.

Return to sport and full function

Many participants are likely to have running as their primary sport, or as a component of their sport, and running is often provocative in PHT especially when faster or uphill. A return to running framework is outlined in the supporting information. Participants are only asked to cease running completely if it causes high pain levels or significantly aggravates their symptoms for more than 24 hours. Participants may instead be asked to cease only some elements of their running (e.g faster or uphill running). For participants who are asked to reduce their training volume, other aerobic fitness activities (swimming, cycling, crosstrainer etc) can generally be substituted in, which has the effect of maintaining aerobic fitness and potentially indirect beneficial effects in managing PHT.82,83Aggravation of symptoms with these forms of exercise is unlikely but participants should monitor latent response.

If participants have been asked to cease running completely, a first return run comprises two minutes of running, in one minute intervals and as part of a longer walk. If tolerance to this load is demonstrated, running volume is increased by one to three minutes per run, depending on the duration of symptoms and historical irritability with running. Once 20 minutes of total running is achieved, distance or speed is then added depending on the participant’s goals.

Hill training can be carefully added once distance is back to the desired voume. The number of runs involving intensity (fast running or hill running) would generally be limited to twice per week, or three times per week for elite or high volume runners with high running frequency. For field and court sport athletes, this may occur as part of scheduled training. Running loads should be quantified where possible to better understand response and whether progressions or regression of loads are required. Running technique is observed by the treating physiotherapist, with emphasis and identifying biomechanical considerations that may increase hamstring tendon load such as reduced lumbopelvic control. Physiotherapists are encouraged to assess and provide feedback prompts on features of running technique that may reduce efficiency or increase hamstring load, including reduced lumbopelvic control, excessive chest/trunk flexion, increased landing noise (associated with overstriding), and cadence (noting that cadence varies with running velocity).

Return to other previously provocative activities such as gardening, squatting, lifting, or kicking, is performed in a similar way, with initially low volumes and then gradual increases based on symptoms during and after activity.

Combining exercise stages

The stages utilized in this intervention vary depending on the individual participant. Early-stage exercises are structured on a two day cycle (Table 2), with Day 1 including prescribed exercises and Day 2 for non-provocative exercise e.g. other aerobic fitness or upper body strength training, plus additional Stage 1 exercise if indicated. Stage 4 exercise is added to Day 1 when indicated (generally after 1-2+ months of intervention). Participants who do not undertake running-based sports do not progress beyond this structure.

If Stage 5 exercises are indicated, the participant moves to a three day cycle, with Day 1 including stages 1/2/3 +/- 4, Day 2 including Stage 5 exercise and eventually modified training, and Day 3 a light day involving non-provocative exercise +/- Stage 1 if indicated.

Participants are encouraged to continue maintenance exercise upon reaching their goals (e.g. return to normal training), this typically involves two to three exercises from Stages 1-3 which are performed twice weekly. Participants are briefed on limitations for activity levels in the future, rapid increases in high load activities, and consecutive high tendon load days should be avoided, and in some cases specific activities (e.g. full depth, heavy dead lifts) should be avoided indefinitely.

CONCLUSIONS

This clinical commentary outlines an individualized physiotherapy intervention for the treatment of PHT. This intervention involves education, graded strengthening, initial reduction and then increase in compressive loading, auditory cuing, contralateral training, lumbopelvic control, latent pain monitoring, and a graded return to previously provocative activites. It allows treating practitioners a flexible stage-based intervention for treatment of PHT using clear principles of tendinopathy management. The protocol is currently being used in a RCT comparing individualized physiotherapy versus shockwave therapy.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

_and_modified_depth_lunge_(b).png)

_and_modified_depth_lunge_(b).png)