INTRODUCTION

Dance is a complex sport requiring years of training to develop appropriate flexibility, strength, motor control, coordination, and endurance. Dancers who train in the genre of classical ballet often begin their studies in childhood as mastery of this art form takes years of dedicated practice. At the professional level, rigorous training, rehearsal, and performance schedules predispose this population to injury.1 Elite ballet dancers continuously subject their bodies to high levels of mechanical stress, which can lead to musculoskeletal injuries. The prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries among professional dancers ranges between 20% and 84%, with the highest prevalence in ballet dancers.2

Overuse injuries account for up to 75% of all ballet injuries due to systematic overload of the musculoskeletal system during long training hours.3,4 The stresses of dance may lead to overuse injuries associated with repetitive sports performance, but also occur as the result of acute trauma.5,6 Acute traumatic injuries may result from a loss of balance, fatigue, or a missed landing from a leap, turn, or jump during dance skills training.6 The foot and ankle are injured most frequently among ballet dancers, with higher rates reported in females.7 Common lower extremity (LE) injuries include ankle sprains, Achilles tendinopathy, calcaneal apophysitis, plantar fascial strain, ankle impingement, flexor hallucis longus tendinitis, Lisfranc injuries, metatarsal fractures, sesamoid injuries, and hallux deformities.1 In a prospective study of 99 professional ballet dancers (male and female) over a one-year period, a total of 196 injuries occurred, equating to an injury rate of 1.9 injuries per dancer per year. Among the female dancers only, injuries to the ankle and foot accounted for 53.2% of the reported injuries.4

Reports of acute traumatic fractures in this athlete population are limited; the majority of current literature describes the incidence and rehabilitation of stress fractures, which occur most frequently in the tibia and metatarsals.2 While case reports on stress injuries of the great toe, second metatarsal, and sesamoid bones have been published, acute or stress fractures to the phalanges of the foot have rarely been described in ballet dancers or other athletic populations.6,8 Additionally, the body of research on a ballet-specific return to sport protocol for any injury is limited; the novel return to sport protocol outlined by Glasser et al. is the first of its kind to provide body region and late-stage rehabilitation recommendations for professional ballet dancers.3

Physical therapy rehabilitation of foot and ankle injuries among professional ballerinas presents unique challenges due to dance training volume, shoe wear, skills performance, and sustained positioning requirements. A variety of classical ballet movements are performed in the demi pointe and en pointe positions, both of which increase the force of plantar flexor, toe flexor, and foot intrinsic muscle exertion across the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) and ankle joints. The demi pointe position is achieved by rising to the balls of the feet, maintaining the ankle in plantarflexion with MTP joint extension between 80° to 100°; in this position, the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) acts as the primary foot stabilizer and is loaded with up to three times more force across the first MTP joint due to end-range extension positioning.9 En pointe position requires a dancer to rise to the tips of the toes in a pointe shoe with a stiff papier-mâché toe box, which provides stability to the foot and ankle. The position is characterized by sustained plantarflexion and axial loading through the toes with support provided by the cardboard shank, or sole, of the shoe.10,11 Anecdotally, ballet dancers report discomfort with en pointe positioning and compression from the pointe shoe, which may be due to shoe-related and intrinsic (foot and toe structure) factors. Dancers may report blisters, bunions, broken toenails, and skin breakdown with extended wear of pointe shoes.10

Although foot and ankle injuries are prevalent among dancers, evidence detailing the rehabilitation of an acute fracture in this body region is lacking. The purpose of this case report is to describe the physical therapy management of a professional ballerina post-traumatic fracture of the proximal phalanx of the fourth toe. Treatment programming and the dancer’s progressive return to dance training were determined and modified using the most current literature on ballet rehabilitation for the subject’s safety and to optimize long-term functional outcomes. The treatment framework was developed using the available literature, the therapists’ clinical judgement, general rehabilitative guidelines for LE fracture, and the subject’s personal experience with the sport. The authors aim to contribute to the body of literature on successful fracture rehabilitation and to encourage further research on return to sport protocol and testing for this population.

CASE DESCRIPTION

The subject of this case report was a 27-year-old dancer employed by a professional ballet company. The case report was granted IRB approval through an expedited submission through the affiliated university’s Institutional Review Board. The subject’s informed consent was included in the review process for publication of the case. Within the company, her roles included performing in five to six shows per season, choreographing and teaching youth ballet classes, and attending company rehearsals throughout the week. During the height of the performance season the principal dancers in the company rehearsed for shows and taught classes up to nine hours a day. In addition to dancing during the workday, the subject maintained her personal health and fitness through personal dance rehearsals, resistance and flexibility training, and participating in local yoga and Pilates classes.

Ten months prior to her initial evaluation, the subject sustained her initial injury in rehearsal upon landing from a grande jeté, a leap in which a dancer jumps from one leg to the other.3 She reported landing on her left fourth and fifth toes, forcing them into a flexed, or “crunched,” position. She recalled feeling acute pain in her toe and stopped dancing after completing her routine. Plain film radiographic imaging revealed a nondisplaced fracture of the proximal phalanx of the fourth toe with a small section of avulsed bone along the distal and lateral surface of the shaft. The subject’s physician decided against surgical resection of the avulsion at that time. She began to dance with modified activities in a flat, or non-rigid, shoe after one week, but did not attempt to dance in pointe shoes until the fifth week post-injury.

Prior to physical therapy rehabilitation, the subject reported continuation with rehearsals and performances and experienced pain and difficulty with performing high-impact leaps and jumps, wearing pointe shoes, and achieving en pointe position. A cortisone injection was administered two months post-initial injury, which temporarily allowed the subject to tolerate the compression of the pointe shoe toe box and forces of en pointe positioning. The effects of the cortisone injection wore off in the fifth month post-injury and the subject was required to return to modified dance activities. At eight months, she underwent surgery to resect the avulsed bone and was referred to physical therapy for rehabilitation. Physical therapy was initiated two months post-surgery, at which time the subject had been cleared by her physician for weight bearing as tolerated (WBAT) and modified dance activities.

Examination, Evaluation, and Diagnosis

The initial physical therapy examination included a subjective history interview, objective examination, home exercise program (HEP) administration, and the completion of the OPTIMAL. The subject’s past medical history, mechanism and history of injury, occupation, prior level of function (PLOF), and personal goals for physical therapy were collected in the subjective interview. She reported little pain upon presentation to the clinic (1/10 pain on a numerical rating scale [NRS]) but noted that rising to her toes, jumping, running, and wearing pointe shoes aggravated pain symptoms. Relieving factors included rest, foot, ankle and toe stretching, and massage. Upon evaluation, she had returned to light dance activities in a flat shoe and had not attempted jumping or dancing en pointe.

Self-report data was collected using the validated Outpatient Physical Therapy Improvement in Movement Assessment Log (OPTIMAL).12 The difficulty baseline section of this outcome measure allows the subject to identify the activities they most wish to address in therapy and their perception of their functional status with each activity. In this case, the subject reported moderate difficulty with balance and much difficulty with climbing stairs (3.00 and 4.00 points respectively, with a score of 5.00 indicating an inability to perform the activity). Additionally, she reported much difficulty (4.00 points; 11.00 points total out of a possible 15.00) with the performance of a single limb relevé. A relevé is a ballet skill in which the dancer rises to the balls of the feet in a flat shoe or onto the toes in a pointe shoe3; this position is used frequently within other dance skills and as a transitional movement between dancing on a flat foot and en pointe. The subject’s self-reported difficulty with this skill informed the development of her plan of care, as her ability to achieve this position played a vital role in her ability to train and perform with her peers and fully return to her occupation.

The objective examination included a gait analysis, manual muscle testing (MMT), palpation, joint mobility testing, and flexibility testing. Findings from gait analysis and palpation of the medial and lateral ankle ligaments were unremarkable. Ankle dorsiflexion, inversion, eversion, and plantar flexion MMT of the left ankle was graded as 4+/5. Slight restriction was noted with flexibility testing of the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. Anterior and posterior glides of the fourth MTP and interphalangeal (IP) joints were hypomobile and painful on the left. Swelling was visible at the proximal IP joint, but the incision site and surrounding skin were healthy. Initial goals were written for the subject according to the objective findings and included decreasing pain at the fourth toe MTP and IP joints to 0/10, improving four-way ankle strength to 5/5 with MMT, and subject independence with an HEP for ankle strengthening. Additional, subject-reported goals were to return to jumping, leaping, and achievement of the relevé position in dance rehearsals.

Diagnosis/Prognosis

Upon presentation to physical therapy, the subject had received medical clearance for rehabilitation and return to modified dance activities with follow-up plain film imaging to confirm appropriate healing at the surgical site. The physical therapy diagnoses, informed by the objective exam and the evaluating therapist’s prior clinical experience, were left fourth toe MTP and IP joint stiffness and L ankle weakness with a subsequent encounter for other orthopedic aftercare. The therapist hypothesized that the subject had a good prognosis with rehabilitation due to her motivation to participate in therapy, her personal experience with resistance, flexibility, and balance training, and her expertise in the movements of classical ballet. The treatment course was developed to focus on improved joint range of motion (ROM) of the left fourth toe, muscle function improvements of the intrinsic muscles of the left foot, and re-integration of balance, proprioceptive, and functional dance movement training. The evaluating and treating therapists guided the subject’s progressive return to full dance participation with frequent objective reassessments, the subject’s subjective comments, and her skills-specific needs for safety and optimal function in dance rehearsals.

Interventions

The subject attended 18 therapy visits over an eight-week period. In conjunction with standard physical therapy, she continued with personal resistance and flexibility training at her local gym and progressively returned to teaching youth ballet classes and attending company rehearsals. Due to the lack of evidence for a post-traumatic fracture rehabilitation protocol for ballet, the plan of care was developed to address the subject’s activity limitations and participation restrictions at work. Daily therapeutic exercises and manual therapy techniques were modified and progressed according to the intensity of the subject’s daily dance schedule, her reports of pain, muscle fatigue and delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), and the therapists’ manual assessment of swelling and mobility of the affected joints. A broad description of the in-clinic treatment program is outlined in Table 1. Additionally, the Foot and Ankle Injury section of the Glasser protocol was utilized to inform timing for the reintroduction of dance skills, particularly training skills en pointe.3

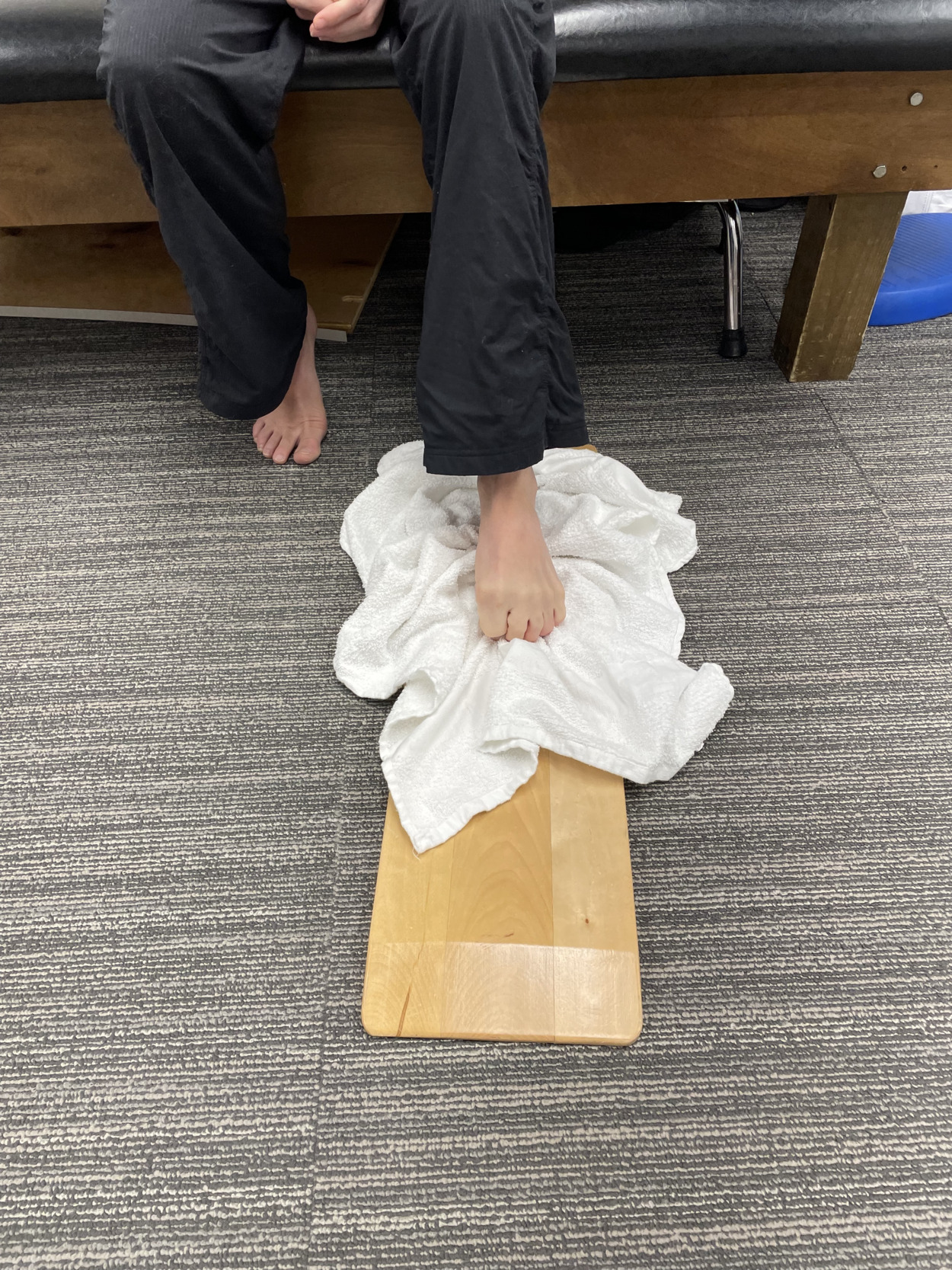

During the initial four weeks of treatment, interventions were prescribed using a limitations-based approach. Initial goals were improved ROM of the fourth MTP and IP joints and decreased pain with activities that increased the weight bearing (WB) requirements of the left foot, such as rising to toes and climbing stairs. Manual therapy techniques consisted of grade II and III anterior and posterior mobilizations to the fourth MTP and IP joints for improved mobility and to reduce post-surgical connective tissue adhesions. Neuromuscular re-education and muscle strengthening exercises for the ankle and intrinsic foot musculature were implemented to address strength and balance impairments (Figure 1). The initial HEP complemented the subject’s in-clinic treatment, with an emphasis on retraining the foot intrinsic muscles to support and elevate the medial longitudinal arch of the foot and standard four-way ankle strengthening. Cryotherapy with a cold pack was administered as needed to address increased pain and swelling and to reduce DOMS after therapeutic exercise.

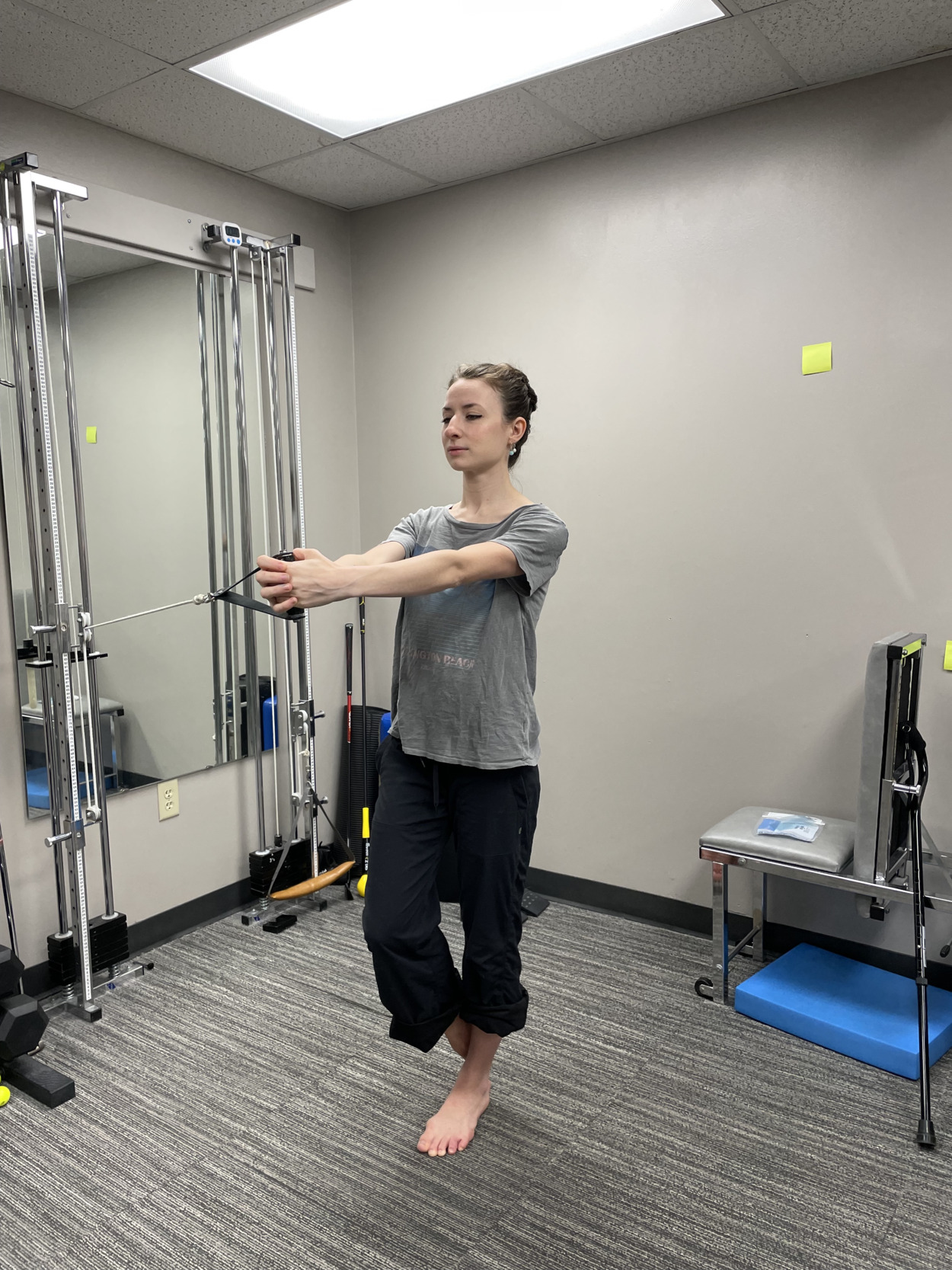

Over the following four weeks, the subject demonstrated improvements in muscle strength and endurance, as evidenced by frequent objective re-assessments, increased tolerance to physical activity, and gradual reintroduction of turns and jumps in dance rehearsals. She reported decreased soreness at the surgical site with a progressive return to her dance training and exercise activities like hiking, swimming, Pilates, and resistance training. Single-limb (SL) balance activities were initiated in the clinic including SL Pallof press, ball toss, and star drill exercises (Figures 2-4). Shuttle Systems™ double and single-limb leg press, jumps, and heel raises were implemented for resistance and plyometric training of the lower extremities to improve plantar flexor muscle endurance and force production.

Return to Dance En Pointe

Training en pointe was reintroduced in the fourth week of therapy and coincided with the beginning of the subject’s formal dance season. To facilitate this transition, progressive resistive LE exercises were implemented to promote axial loading and optimal tissue maturation at the wound site.13 While progressive resistive exercise and tissue loading are fundamental aspects of rehabilitation post-traumatic fracture, this subject required more advanced training prior to her return to classical ballet performance. Creativity and collaboration between the therapists and the subject were required to develop a tailored rehabilitative plan for the subject’s successful return to her occupation.

A functional priority for the subject was a pain-free return to performing en pointe. Clearance to return to pointe training was determined by her completion of the sixth stage of the Foot and Ankle Injury Return to Ballet Protocol, in which the dancer should be able to perform certain high-impact jumps and work with a partner without pain in a flat shoe.3 Upon re-evaluation in the sixth week of treatment, she reported difficulty with tolerance of the compression from the pointe shoe toe box and maintaining demi pointe position. At this time, the subject was able to perform double limb pointe skills unassisted but was limited to training SL skills with upper extremity support at the barre due to pain.

In combination with progressive tissue loading with exercise in physical therapy, the subject and therapists discussed training part-time in a de-nailed pointe shoe to reduce pain and improve tolerance of en pointe positioning. The process of de-nailing a pointe shoe involves removing a portion of or the entire cardboard shank to increase shoe flexibility (Figures 5-6). The subject was educated regarding safety considerations of dancing in a de-nailed shoe, as decreased shoe rigidity leads to an increased load placed on ankle and foot stabilizing muscles. The introduction of the de-nailed shoe allowed the subject to train en pointe for up to 40 minutes at a time and benefitted her overall stamina and strength in personal and group rehearsals. As the subject’s tolerance of pointe shoe wear improved, she transitioned to a pointe shoe model with a less rigid, intact shank and wider toe box (pre-injury: 5XX wide with hard shank; post-injury: 5XXX wide with standard shank). These variations in shoe shape and rigidity contributed to her successful long-term outcomes by allowing for an accelerated return to pointe dance training with an optimal, safe, and less painful pointe shoe fit.

Interventions in the clinic were tailored to improve the subject’s tolerance of axial WB through the toes en pointe and muscular endurance of the toe flexor and plantar flexor muscle groups. In addition to experiencing pain in demi pointe position, the subject noted that the pain felt muscular in nature rather than a boring, bone pain as was felt prior to surgical intervention. The treating therapist theorized that decreased toe flexor endurance may have contributed to pain in this position due to the increase in muscle exertion force applied across the WB MTP joints. Exercises developed to train functional strength and endurance in this position included resisted heel raise training with load, timing, and joint angle modifications and continued neuromuscular re-education of the foot intrinsic and toe flexor musculature. Dynamic stability and resistance exercises for the proximal hip musculature were implemented to improve strength and balance with en pointe skills (Figures 7-8). Training surfaces, duration, tasks, and cognitive load were varied to adequately challenge the subject and identify endurance deficits on the affected limb.

In preparation for discharge from physical therapy, the current literature for return to sport in ballet was consulted to develop a plan for the progression of dance training duration and skills repetition volume. For personal, unsupervised rehearsals, pointe training was limited to 45 minutes until compression pain from pointe shoes had fully resolved; it was recommended that the practice of more difficult dance skills be limited to 5-10 repetitions per session until the subject had returned to dance en pointe in the center of the floor without losses of balance (LOB).3 The Modified Pearce’s Soreness Rules were introduced to the subject as a tool to assess pain and determine when the progression of skills difficulty was appropriate in rehearsal. The criteria for Pearce’s rules define soreness as pain greater than 3 out of 10 on a NRS and suggests that it is appropriate for the athlete to continue per protocol recommendations if soreness resolves within the warm-up period. The athlete should take two days off to rest in the case of persistent or recurrent pain during the training session and prior to progressing with the return to sport protocol.14

OUTCOMES

Within the first week of therapy, the subject noted increased fourth toe mobility and subsequent improvement in activities participation. She was able to hike with mild soreness that resolved after activity and began training dance skills at a modified level. During the second and third weeks of treatment, she reported fluctuating soreness and pain with the re-introduction of dance skills and the ability to jump in a soft shoe without pain. She donned pointe shoes for the first time post-operatively in the fourth week of therapy with significant pain from the compression of the toe box on the affected joint. She reported continued improvements in dance skills tolerance without the use of her pointe shoes. She noticed a decrease in pain with dance skills performance en pointe and improvements with turning skills within the fifth week of therapy.

The subject was re-evaluated at six weeks and demonstrated an improved self-reported OPTIMAL score of 4.00 (improvement by 7.00 points). She reported having little difficulty with balance and SL relevé and no difficulty with stair climbing. Pain was reported as a 3/10 at worst with eccentric SL lowering activities from the demi pointe position and putting pressure through her fourth toe in the flexed position. Ankle strength with MMT had improved to 5/5 in all planes and fourth proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint mobility was hypomobile but no longer painful. At this time, notable remaining functional limitations were static and dynamic balance in SL stance and eccentric plantar flexor and toe flexor strength, as evidenced by difficulty with maintaining demi pointe and pointe positions. Based on these findings and the beginning of the subject’s formal dance season in the sixth week of therapy, continued skilled physical therapy care was indicated for functional training to address remaining skills deficits and provide dance-specific interventions and subject education regarding the appropriate dosage of studio dance training. The therapists provided written communication to the subject’s employers regarding activity modifications for the subject’s safety during rehearsals until clearance for full activities participation was provided.

In weeks six and seven, the subject’s endurance and comfort with training en pointe quickly improved. At this time, her tolerance of training in a pointe shoe and SL relevé strength were progressively improving with therapeutic exercise interventions and dance rehearsals. Physical therapy interventions focused on improving strength and tolerance of demi pointe positioning, dynamic balance training, and psychological readiness for return to the performance of traveling sequences en pointe in the center of the floor. The subject continued to self-monitor her abilities and fatigue in rehearsals and communicated with her employers about necessary activity modifications.

At the end of the eighth week, the subject was re-evaluated and demonstrated no toe pain or strength deficits; MTP joint mobility was within normal limits (WNL) and slight restriction was found at fourth PIP joint. The subject exhibited no functional limitations with toe flexion or extension. No activity limitations were reported with re-administration of the OPTIMAL (score of 0.00 with an improvement by 4.00 points from re-evaluation in week six), with a notable resolution of her prior difficulty with achieving the SL relevé position. At this time, the subject was able to train en pointe for up to an hour without abnormal pain or soreness from the pointe shoe. Along with her ability to train en pointe for a longer period, she had returned to the performance of higher impact jumps and trained skills such as turns and traveling sequences without pain. The subject reported confidence with discharge from physical therapy and making a full return to dance training.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this case report was to describe the physical therapy course of a ballerina at the professional level who achieved a full return to sport post-traumatic fracture. To the authors’ knowledge, limited current research is available regarding a return to sport protocol and testing for an acute, traumatic fracture among this athlete population. At present, most of the clinical literature regarding ballet-related injuries provides general instructions for balance, jumps, turns, barre, and center training progressions and lacks body region-specific and late-stage rehabilitation specifications. Body-region specific recommendations in ballet rehabilitation benefit the dancer by formatting skills progressions according to the site and mechanism of injury and difficulty of specific ballet movements.3

The Glasser et al. novel return to sport protocol provides rehabilitative recommendations for the professional ballet dancer according to body region and type of injury. In this subject’s case, the therapists referenced the foot and ankle injury sub-section of the protocol to inform the order and timing of the subject’s return to barre and center skills and en pointe training. The foot and ankle protocol consists of six stages with criteria for pain-free, independent performance of certain ballet skills before progression to the next stage. Skills in all stages should be performed in a flat shoe with clearance to progress to en pointe training upon completion of the sixth stage. The subject’s medical clearance for light dance activities coincided with the start of physical therapy and she was able to quickly progress to the fourth and fifth stages of the protocol under the therapists’ supervision. These stages outline the progression from turns on the injured leg to petit allegro jumps, or small, quick jumps with a landing on one or both legs (Table 1, week 3). The performance of pain-free high impact jumps, like the grand jeté, and return to partner work are included as criteria in stage six and should precede the re-introduction of en pointe training.3

Upon completion of the sixth stage, the subject continued with jumps and turns training in personal rehearsals; the focus of physical therapy interventions transitioned to promoting the subject’s tolerance of relevé positioning and improving dynamic core and hip stabilization while dancing en pointe. The subject’s reports of her function with en pointe training informed therapeutic exercise prescription during the later weeks of her rehabilitation; her chief complaints included pain in demi pointe and SL relevé positions and a general sense of impaired body mechanics, global LE strength, and muscular endurance en pointe. To address the reported deficits, SL dynamic balance exercises initiated in weeks three and four of treatment were progressed to challenge the subject’s control of her WB LLE under various conditions; hip and core endurance activities were implemented in weeks six to eight to promote proximal muscular strength and proper body mechanics with SL relevé, turns, and high impact landings (Table 1). Calf raise activities with timing and load variations were progressed to promote the subject’s strength in demi pointe, with full resolution of pain symptoms in this position at the time of discharge. While this case report describes the positive outcomes for one professional ballerina with an acute, traumatic toe fracture, the timing and interventions included in this rehabilitative program may or may not be beneficial for other individuals with the same or similar injury. In this case, a tailored physical therapy plan of care combined with a body-region specific protocol and the subject’s motivation to return to full dance activities led to a successful rehabilitation outcome.

The quantitative outcome measure administered in this physical therapy course was a self-report measure. While self-report measures are effective for capturing a subject’s perception of their functional status, some may argue that objective or performance-based return to sport testing should have been implemented prior to discharge as a more objective assessment of functional status. A previous study utilized the Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT) and single leg hop for distance (SLHD) test in an injury prevention program for professional dancers but currently there are no validated return to sport testing protocols for this population.15 The SEBT is used to assess SL balance, motor control, and LE strength and the SLHD examines ankle and knee stability and muscle power. These tests, among others, could have been used to identify asymmetrical LE strength and balance deficits and provide functional objective data to strengthen the discharge plan. Further research is needed to determine the validity of these and other return to sport tests in determining the readiness of a ballet dancer to return to sport and their relevance to the unique skills and movements required by this genre of dance.

CONCLUSION

This case report illustrates the successful rehabilitation of a high-level dance professional post-traumatic fracture. Various interventions were integrated into the physical therapy course with a focus on a progressive return to high impact activities and shoe wear modification for improved dance skills performance and tolerance of en pointe positioning. Further research regarding the rehabilitation of traumatic fractures in this athlete population is vital to optimize long-term outcomes, prevent re-injury, and facilitate a safe and full return to advanced ballet performance.

Corresponding Author

Madeline G. Morgan

PTC 313

Department of Physical Therapy

201 Donaghey Ave.

Conway, AR 72035

Fax 501-450-5822

Phone 479-340-4232

Email mswimnwa@gmail.com

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.