Introduction

Running, a globally popular and accessible sport, has seen a significant rise in popularity over the last five decades.1 However, as participation increases, so does the incidence of running-related injuries (RRI), which often pose challenges for both recreational and professional athletes.1 Notably, knee injuries are the most prevalent, constituting 28% of all RRI, with patellofemoral pain (PFP) alone accounting for 17% of these injuries.2,3 Among amateur runners in the general population, the incidence is reported at 1080.5 per 1,000 person-years. Adolescent amateur athletes exhibit prevalence rates ranging from 5.1% to 14.9% over a single season, with female adolescent athletes specifically showing a higher prevalence of 22.7%.4

Longer-term follow up data indicate that a large number of individuals with PFP continue to experience symptoms and unfavorable outcomes. Indeed, the proportion of those reporting chronic symptoms is alarming, from 40% after a one-year follow-up, 57% after 5-8 years and up to 91% after 18 years.5–7 Implications of this poor prognosis are severe, patients with PFP have major limitations of daily activities, work, and athletic participation and Blønd & Hansen, reported that 74% of individuals experiencing PFP will limit or stop sport participation.8,9

Increased peak hip adduction, internal rotation, and contralateral pelvic drop, along with reduced peak hip flexion, are recognized as risk factors for runners with PFP.10 These biomechanical alterations can lead to pain and discomfort during physical activities, particularly running, thereby exacerbating challenges for individuals with PFP.11 Abnormal mechanics, such as increased knee valgus or muscle weakness in the hip and quadriceps, can lead to uneven distribution of forces across the PFJ, exacerbating the condition.12

Among the interventions aimed at reducing patellofemoral joint (PFJ) load, whether temporarily during the recent onset of PFP or in the long term during prolonged symptom duration, Running Retraining technique (RRT) are a preferred intervention aimed at improving the capacity of runners to learn a new motor pattern to reduce PFJ stress during the stance phase.13,14 This can be achieved either by decreasing compression forces in the joint or by distributing forces over a greater joint contact area.15 To date, several studies have demonstrated reductions in symptoms in runners with PFP up to three months after the end of a two-week intervention.16,17

Another way to reduce the PFJ load during running is to improve the overall control of the lower limb. Better control will allow for a more even distribution of stresses across the entire lower limb.12 In this regard, neuromuscular exercise (NME) programs aim to improve sensorimotor control and functional joint stability through exercises that engage multiple joints and muscle groups.18 Adjustments in exercise intensity, complexity, and environmental factors are employed to progressively challenge and may enhance muscular coordination. The efficacy of such NME in breaking the cycle of poor biomechanics and recurrent injuries has been supported by some authors in randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews, highlighting their role in enhancing proprioception, functional outcomes, and symptom reduction.19–22

This scoping review examined the use of RRT and NME, either combined or standalone, in runners with PFP. This expansive overview enabled the provision of a broad perspective on the interventions utilized in clinical practice, thereby helping practitioners and researchers understand and further investigate this prevalent issue. Unlike meta-analyses or systematic reviews that focus on more narrowly defined questions and require a critical analysis of study quality, this scoping review aimed to summarize the existing literature and identify gaps in knowledge and practice.23

Materials and methods

The methodology for this scoping review was guided by the frameworks proposed by Arksey and O’Malley and the Joanna Briggs Institute.24,25 This review was designed to systematically explore the available literature and identify key concepts, research gaps, and evidence surrounding the use of RRT and NME programs in runners affected by PFP.

Selection Criteria

The PRISMA-SCR framework guided this scoping review, defining inclusion and exclusion criteria based on: population, concept, and context (PCC). In terms of population, the study targeted PFP patients who were either recreational or amateur runners. Inclusion criteria specified runners at any level, including amateur, semi-professional, or professional, aged above 18 years old and participating in at least one local event within the six months preceding their participation in the included study. Exclusion criteria were applied to individuals engaged in sports other than running to maintain focus on running-specific dynamics. For the concept, our inclusion criteria were focused on studies that incorporated NME or RRT aimed at treating PFP. The definition of NME was derived from the guidelines established by the American College of Sports Medicine.26 Studies that published protocols without reporting any results were excluded. . Regarding the context, this study encompassed research involving patients with PFP who were actively practicing running excluding those with a history of knee surgeries, other knee pathologies, such as meniscal injuries, patellofemoral arthritis, or ligament injuries or paediatric populations to concentrate solely on adult runners. As for the types of studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, primary research studies, guidelines, and case series were accepted, but excluded conference abstracts. Articles included in systematic reviews, as well as the bibliography of selected articles, were analyzed and manually included in the final result. For more information see Table 1.

Study selection

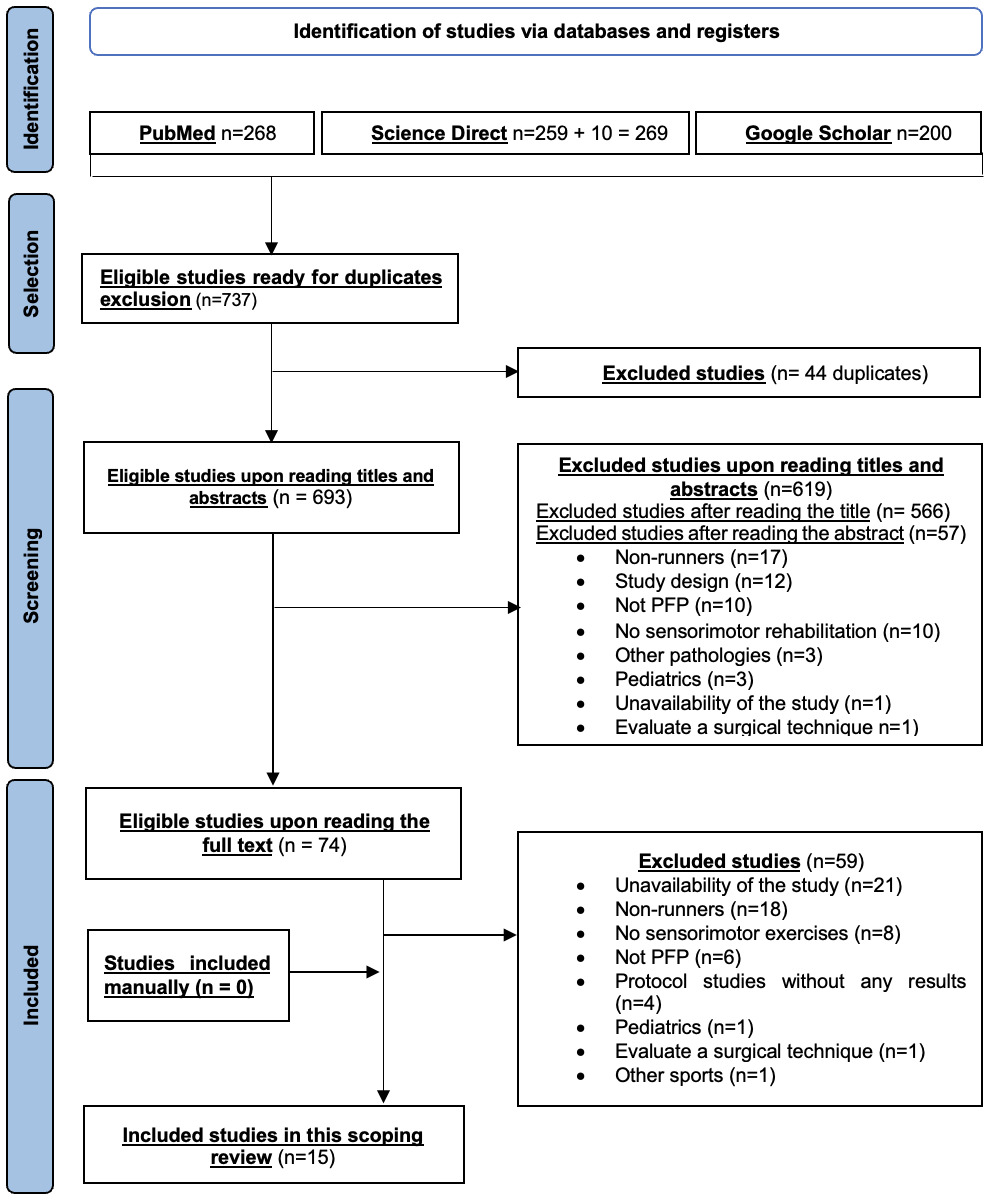

The study selection was conducted in several structured phases. Firstly, we formulated three research queries across three databases in April 2023: MEDLINE (PubMed), ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar based on the following keywords: “neuromuscular exercises”, “PFP”, “runners” and “exercise”. The search strategy was implemented in both English and French across all database, except for PubMed, which was searched only in English due to its primary indexing of English-language journals (Supplementary Table 1).

Secondly, the Zotero software was used to organize the retrieved articles with the “tags” feature aiding systematic selection. Thirdly, we removed duplicate articles. Fourthly, two independent reviewers (MF and TG) excluded irrelevant articles, initially by reviewing titles and abstracts. Finally, among the remaining articles, The full text and the availability of detailed RRT and NME protocols were examined to finalize the selection. A third reviewer (AR) resolved any discrepancies and reach a consensus on inclusion when necessary. The inclusion criteria, as outlined before, were critical in identifying the most relevant articles.

Data extraction and analysis

Two independent reviewers (MF and TG) conducted the data extraction. This process involved gathering information such as the authors’ names, publication year, article titles, journals, study nationality, types of exercises. To ensure comprehensive and standardized reporting of exercise interventions and increase the likelihood of successful implementation of the research program in clinical practice, we have decided to extract all the items of the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) for each study, except for items 2-5, 11-12, and 16 in the narrative review, as they were not applicable to this type of study, to evaluate the reporting quality of the studies.27 Moreover, the types of study designs were also collected.

Additionally, this review explored diverse modalities of NME and RRT protocols used in studies. For the NME protocols, our analysis concentrated on the FITT (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type) components and key factors, such as rest intervals and the prescribed speed for executing the exercises. “Frequency” referred to the prescribed days per week. “Intensity” included resistance, total repetitions, and/or the overall load per session. “Time” was defined as the total duration of the program in weeks. “Type” was not considered, as all included exercises were NME. We also assessed the type of feedback provided (tactile, visual, and auditory), range of motion, any additional resistance, exercise progression, support surface (whether stable or unstable), and clinical guidance.

Similarly, the review of RRT focused on the number of sessions, their frequency, RRT initiation point during rehabilitation, clinicians’ instructions, running cadence, type of feedback and removal method, the use of minimalist footwear, speed adjustments, self-rehabilitation practices, and overall training progression. Highlighting these types of information is essential due to their influence on RRT outcomes. Minimalist footwear can enhance running efficiency, while gradually increasing running speed improves performance and running economy. Self-rehabilitation supports recovery, and a structured progression in training, including adjustments to footwear and speed, contributes to achieving optimal outcomes.28,29

Results

Flow of study selections

The selection process of studies for this scoping review is detailed in Figure 1. Only 15 studies ultimately met the strict eligibility criteria for inclusion in this review.

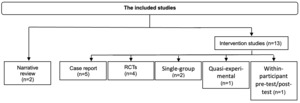

Broader perspective

In terms of the study focus, eight studies exclusively addressed RRT.16,17,30–35 An additional five studies investigated a combination of NME and RRT,13,36–39 while only two studies focused solely on NME (Table 2).40,41 The types of studies included in this review are illustrated in Figure 2. Both narrative reviews have a CERT score of 5/1137,39 while the other types of studies, their CERT score ranged between 7 and 17 over 19 (Table 2).13,16,17,30–36,38,40,41

Geographically, the distribution of the studies varied, with the majority (46%) conducted in North America. Studies that explored NME alone, or the combination of NME and RRT, were exclusively conducted in Europe and South America. In contrast, studies focusing solely on RRT were predominantly carried out in North America and Australia (table 2).

Synthesis of Neuromuscular exercises

Forward lunges exercise

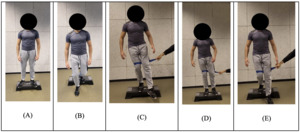

The forward lunge exercise was found and described in three protocols.37,40,41 Only one study introduced this exercise between the 6th and 8th week of their protocol, specifying three sets of ten repetitions.16 They emphasize maintaining a forward trunk inclination to reduce quadriceps dominance and encourage activation of the posterior chain muscles.. The visual feedback is incorporated in two studies37,40 while the auditory feedback is incorporated in one.37 In all three protocols, the forward lunge exercise was performed with both feet planted on the ground, spaced hip-width apart, with the front foot flat and the back foot on tiptoes. Visuals and progression of forward lunges are shown in Figure 4

Single-leg squat

The single-leg squat exercise was found and described in seven protocols13,36–41 with similarities in the NME program leading to combine the studies for analysis.13,36

The exercise was introduced in various stages across the protocols: from weeks 1-8, with specific implementation at week 5 or between weeks 6 to 8.13,36,38,40 In contrast, Rambaud recommended initiating the exercise based on the patient’s pain threshold, starting “as soon as the pain allows”.39

The prescribed sets and repetitions varied, ranging from 2 sets of 10 repetitions, 20 repetitions per leg, to 3 sets of 12. Adjustments were made according to pain levels in several studies.

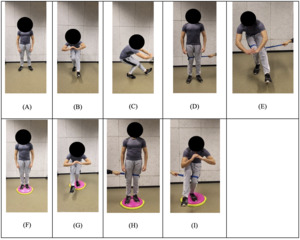

Five studies used a stable surface for the exercise.13,36,38–40 Progression was a key feature in four studies, with variations including increased repetitions, hold time, the addition of an elastic band,13,36 the introduction of an unstable surface,39 or the inclusion of external cues.38 Instructions were emphasized in five studies with a focus on maintaining correct trunk and lower limb alignment.13,36,39–41 Visuals and progression of single-leg squat are shown in Figure 5

Step-down

The step-down exercise was described in three protocols. One study introduced the exercise based on the patient’s pain threshold,39 while two studies introduced this exercise starting from the third week of the program.13,36 Both studies used consistent concepts for sets, repetitions, progression, and instructions across different exercises, with visual feedback being the only feedback mechanism employed during the step-down exercise.13,36 Visuals and progression of step down are shown in Figure 6

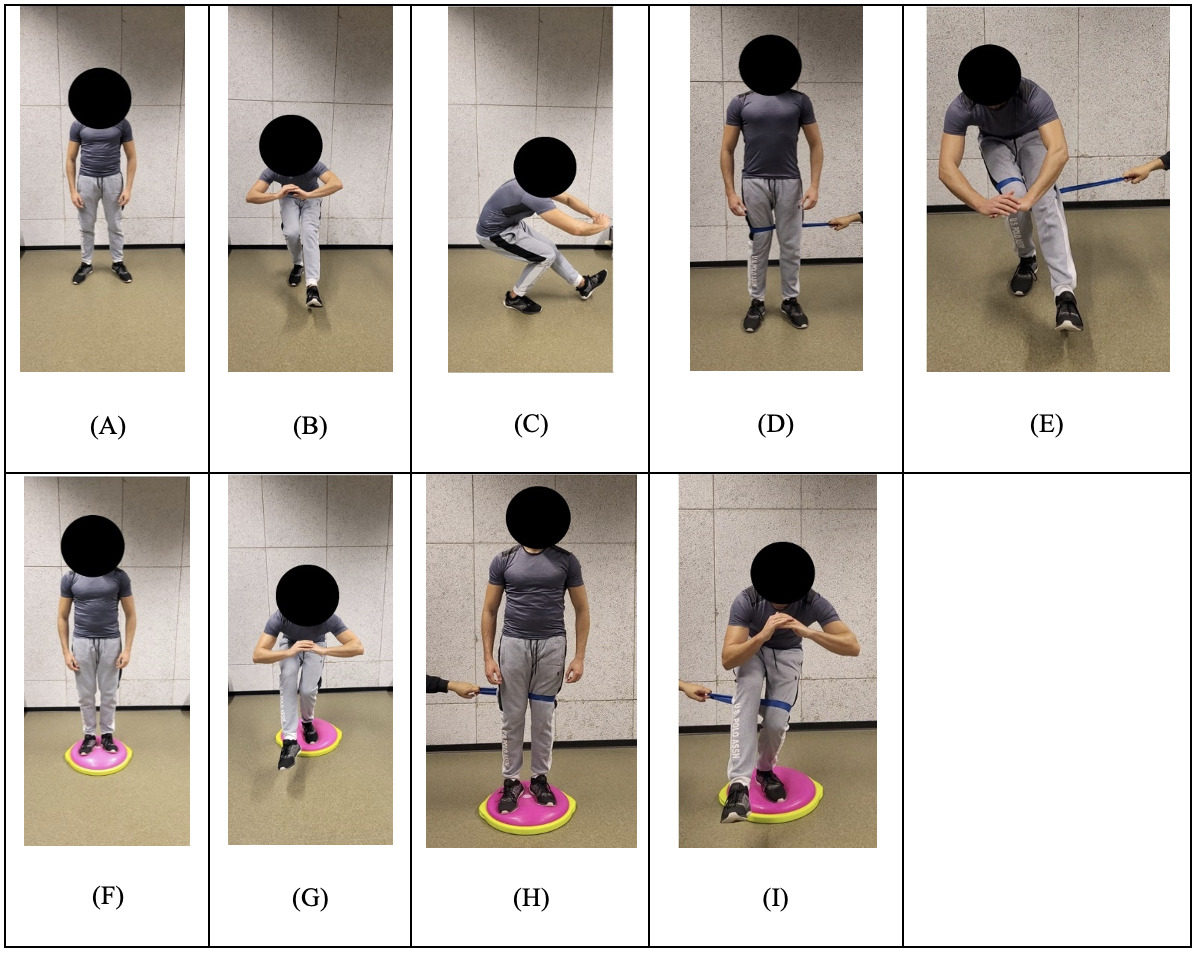

Squat with trunk rotation

The squat with trunk rotation exercise was described in three protocols. One initiated the exercise between the first and eighth weeks of the program,38 while the others introduced it between the fifth and sixth weeks.13,36 Similar to their approach with the step-down exercise, two studies applied consistent concepts for sets, repetitions, progression, and instructions, tailored to the specific requirements of each exercise.13,36 Visuals and progression of squat with trunk rotation are shown in Figure 7

FITT elements

The overall results regarding the FITT components were as follows: Exercise frequency was set at three times per week in four studies.13,36,38,40 However, exercise intensity varied between 1 to 3 sets of 10 to 12 repetitions,13,36,40,41 and was adjusted based on pain levels.38 The duration of the exercise programs ranged from 6 to 20 weeks.13,36,38,40,41 A comprehensive overview of the FITT aspects for the four exercises is also presented in Figure 8.

Synthesis of running retraining protocols

In total, 13 studies were identified that implemented RRT.13,16,17,30–39 A comparative table has been created to analyze the different modalities of RRT used in these studies (Supplementary Table 2).

Number of sessions and frequency

In terms of initiation, one study started RRT from the 9th week,38 while the other began RRT as soon as the patient’s pain levels permitted.39 Regarding the frequency and total number of sessions, five studies implemented a total of eight RRT sessions over two weeks.16,17,33–35

The remaining studies exhibited variations, ranging from a single 10-minute session to one weekly session over twelve weeks.13,30–32,38 Two studies integrated a four to six-week self-rehabilitation program.13,32

Instructions

Rehabilitation professionals provided guidance to enhance muscle activation and adjust kinematic, kinetic, and spatio-temporal parameters. Spatio-temporal adjustments included increasing step cadence by 7.5 to 10% above the habitual cadence.13,16,30–32,38 Kinetic adjustments focused on running with minimal noise and soft landings.13,30,37 Kinematic guidelines recommended adopting a forefoot strike,16,17 maintaining knees apart with the patella facing forward,33–35 keeping a straight pelvis,33 and positioning the body closer.37

Type of feedback

Six studies used auditory feedback alone,13,16,30–32,38 which varied between a metronome,30,32 verbal cues from a physiotherapist,13,16 or both.31,38 Four studies incorporated a combination of visual feedback (using a mirror), and auditory feedback (verbal cues from a physiotherapist).17,34,35,37

Progressive and non-progressive feedback

Five studies implemented a progressive feedback suppression protocol.16,17,33–35 This protocol gradually reduced the feedback provided, beginning the reduction from the fifth session out of a total of eight. For instance, two studies ceased providing feedback in the sixth and final week of their protocol.30,31 One study, in which only one 10-minute supervised session was conducted, discontinued feedback after 5 minutes.32 Similarly, terminated feedback based on the patient’s ability to maintain the correct step cadence effortlessly and consistently.38 This non-progressive cessation of feedback was designed to challenge patients to quickly adapt and rely on their internal feedback mechanisms to sustain the correct movements.

The use of minimalist shoes

Two studies uniquely provided minimalist shoes to patients during rehabilitation process.30,31 However, during self-rehabilitation periods, patients were instructed to use their regular running shoes.

Speed

Three studies determined their speed settings based on the initial running speed observed during baseline tests.30–32 Contrastingly, one study standardized the speed to a steady pace of 6 minutes per kilometer (10 km/h) throughout the rehabilitation process.38 Additionally, one study uniquely based its patients’ running speeds on their performance during a 30-minute run.16

Self-rehablitation

Self-rehabilitation played a prominent component in six studies, underscoring its importance in the recovery process.30–33,36,38 Notably, one study exclusively focused on self-rehabilitation.36 Two studies placed significant emphasis on self-rehabilitation, with 80% of the rehabilitation activities being patient-directed.30,31 Another study incorporated self-rehabilitation to a slightly lesser extent, with a 75% reliance.38

Conversely, five studies imposed restrictions on running outside of structured rehabilitation sessions to control recovery environments and minimize the risk of re-injury.16,17,33–35 In these cases, patients were only permitted to resume running after a designated two-week rehabilitation period16,33 or at the end of the rehabilitation program.17,35 The remaining studies encouraged their patients to resume their usual running program immediately after the two-week period.16,17,34,35

Progression

Overall, the retraining protocols across various studies show a clear progression in difficulty. Many protocols incorporated the removal of feedback as a progression method, whether done gradually16,17,33–35 or abruptly.30–32,38 Eight authors emphasized the timing of progression in retraining.16,17,30,31,33–35,38 For example, some protocols included a 10% weekly increase in training volume or a gradual increase in running time from 5 or 15 minutes to 30 minutes over the course of 12 weeks or 8 sessions.16,17,30,31,33–35 In contrast, only two studies guided progression based on pain levels, either by ensuring that pain remains below 3/10 on the Numeric Pain Rating Scale32 or by proceeding only when the patient is symptom-free.36

Discussion

The primary objective of this scoping review was to explore and identify the description of both NME and RRT rehabilitation modalities in runners with PFP. The results were very heterogeneous. Various NME were performed at different stages of rehabilitation, with the most common instruction being to maintain alignment of the lower limb. Visual and auditory feedback were frequently used. Although the number of sets, repetitions, and rest periods might have seemed insignificant, they were all crucial elements, that were often missing in many studies. The progression of NME took various forms, such as incorporating external focus, external perturbation, or using an unstable surface.

Regarding RRT, the number and frequency of sessions varied, and the utilization of RRT appeared to be an important intervention. Various instructions were given, such as increasing step cadence or minimizing noise while running. Visual and auditory feedback were also commonly employed and could either be maintained or removed over time. Some authors provided recommendations for footwear during RRT. Running speed and progression varied among authors, with several suggesting self-rehabilitation.

The existing literature on NME and RRT rehabilitation for runners with PFP is marked by significant variability in both protocol design and reporting. These inconsistencies create gaps in knowledge that hinder the development of evidence-based guidelines.

While this review highlights the role of RRT and NME in PFP rehabilitation, it is important to consider their integration with other established treatments. Strength training, particularly targeting the quadriceps and hip muscles, has been widely recommended to improve muscle capacity, while foot orthoses, taping, and manual therapy are often used to modify biomechanics and reduce pain.42 Given that NME focuses on motor control and movement retraining, it may complement strength training by enhancing neuromuscular coordination. Similarly, RRT, which emphasizes gait modifications, could be optimized when combined with strength training or footwear adaptations.

Continent trends in runners with PFP

North America and Europe have emerged as the two most dominant continents in research on runners with PFP with nearly half of the analysed studies conducted in North America (46%) and 0 studies from Asia or Africa. This dominance might be somewhat surprising given that Jie Xu et al. identified China and Turkey, as being among the countries most actively studying PFP globally.43 These findings could be attributed more to cultural factors, especially considering that Europe and North America hosts nearly 1,250 to 2,000 marathon events per year, with a combined marathon market share of over 75%. In contrast, Asia ranks third with fewer than 500 marathon events and less than 20% of the global marathon market share.1

Neuromuscular exercises

One study found that the single-leg squat required greater muscle recruitment, particularly of the gluteus medius, compared to the forward lunge.44 Therefore, it would be logical to perform the single-leg squat later in rehabilitation, starting with easier exercises like the forward lunge. Surprisingly, in some protocols, both exercises were initiated simultaneously.40,41 Contradicting, two studies recommend a two-week interval between step-downs and single-leg squats.13,36 Additionally, Baldon et al. used NME with a locked knee, such as the single-leg deadlift and closed-chain hip external rotation, to strengthen pelvic stabilizers while reducing pressure on the patellofemoral joint.40 These exercises are a good alternative before progressing to those with an unlocked knee. All authors agreed on the importance of controlling dynamic knee valgus by aligning the lower limb neutrally in the frontal plane to prevent pain.45

Interestingly, a recent clinical practice guideline did not recommend the use of visual biofeedback on lower extremity alignment during hip- and knee-targeted exercises for the treatment of individuals with PFP.46 In this review, three out of six studies that included single-leg squats used visual feedback (two mirror and one laser). A study demonstrated the importance of visual feedback in reducing forces impacting the patellofemoral joint during a squat, although reducing force does not always equate to less pain.47 Unlike RRT protocols, the authors did not mention whether there was a progressive reduction of feedback or not.

Recovery time between sets and exercises are crucial during NME, considering that muscle fatigue can decrease knee proprioception and neuromuscular control.48 Remarkably, no study specified a rest period between each set and each exercise.

There is a wide variety of exercise progression used in the majority of studies with NME. The only controversial progression was in one study, which involved the use of unstable surfaces.39 While this technique is widely used in clinics practice, there is no robust evidence to confirm its efficacy for PFP patients. For instance, unstable platforms may not be effective for enhancing ankle proprioception and might even hinder proprioceptive feedback from the ankle, favoring feedback from the trunk instead.49 This highlights that the intended progression of an exercise does not always align with its actual impact and further research is needed in this area.

Running Re-Training

Only two studies focused on the timing of initiating RRT.38,39 The criteria for initiating RRT were either the timing (9th week)38 or the absence of pain.39 There was no unanimous response as most studies tested the effectiveness of different RRT techniques/program, and RRT was not part of a comprehensive/multimodal rehabilitation program. These studies mostly involved patients with chronic PFP, suggesting that RRT could be considered in case of treatment failure.

In terms of frequency, number, and duration of sessions, the results varied significantly, ranging from a single 10-minute session13 to a total of 12 sessions.38 This disparity might be explained by the differences in healthcare systems across the countries where these studies were conducted. Some countries, following English-speaking countries grant patients more autonomy with a greater focus on self-rehabilitation, whereas others follow a more paternalistic model with highly structured sessions. However, the majority of studies are consistent with the following protocol,33 which involves eight sessions over two weeks, providing a framework for analyzing the effectiveness of RRT. These protocols may not integrate seamlessly with a multimodal rehabilitation approach for PFP.

Eleven out of the thirteen studies incorporated at least one type of feedback, widely regarded as a critical component of a RRT program.50 One study emphasized that the gradual reduction of feedback enhances motor learning,51 a finding supported by another,50 who observed a stronger effect when feedback was progressively decreased. Surprisingly, only 38.46% (5 out of 13) of the studies implemented a progressive feedback reduction, with Irene Davis contributing as author to three of these five studies. Previous research suggests that simple clinician instructions—such as advising runners to run more quietly—can be just as effective in reducing impact as expensive laboratory feedback equipment.52 Despite its simplicity, low cost, and time efficiency, only three studies adopted this technique.13,31,37

Nielsen et al. found that runners’ progression over a two-week period should remain under 30% to prevent an increased risk of distance-related injuries.53 This guideline was closely followed in two studies. However, five studies implemented a more aggressive progression, with increases nearing 20% per week (40% over two weeks), resulting in an increase from 15 to 24 minutes over three weeks. This variability is understandable, given that only one study has directly evaluated this risk. Additionally, injury risk is influenced by a combination of factors beyond just external load, including biological, physical, psychological, and sociocultural factors.54

Clinical implication

NME and RRT are widely implemented approaches in clinical practice. The significant variability in exercises and parameters presented in the reviewed studies equips clinicians with an extensive range of strategies. This flexibility allows them to customize exercise programs to address each patient’s unique responses and needs, thereby optimizing treatment outcomes. This emphasizes the critical importance of tailoring exercise programs according to each patient’s unique responses and individual needs.55

Limitations

The primary limitation of this review lies in the application of the definition of NME, which consequently influenced the inclusion and exclusion criteria of studies. This category of exercises is quite broad, which complicated the process of selecting or excluding studies. The lack of precision in some studies required us to make subjective interpretations, which may have affected the consistency of the review.

Despite employing rigorous and transparent methods throughout the process to ensure a comprehensive literature search, it is possible that some relevant studies were overlooked. The inclusion of studies was limited to those published in English and French, which may have introduced language bias and restricted the scope of the findings Finally, some studies were authored by the same researchers or research teams, potentially emphasizing certain perspectives within the field.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights a significant research gap in the understanding and application of NME and RRT programs for treating runners with PFP. The variability and lack of standardization in current studies underscore the need for more comprehensive and methodologically sound research. Researchers must ensure that exercise programs are reported in detail and aligned with the CERT guidelines. Inadequate reporting or unclear classification of exercise programs can compromise the quality of evidence syntheses and, ultimately, their findings.