INTRODUCTION

Dry needling (DN) is an evolving intervention utilized in patients and clients with many musculoskeletal and neuromuscular pathologies to treat pain, functional impairments, and disabilities. DN is an intervention that involves the insertion of a thin filiform needle into muscles and other soft tissues, such as ligaments, tendons, and scar tissue.1–3 This intervention is an umbrella term that encompasses trigger point DN, intramuscular manual therapy, DN with intramuscular stimulation, superficial DN, and spinal segmental sensitization model.1,4 DN is used by many healthcare professionals, including physicians, athletic trainers, chiropractors, and physical therapists.5,6 Within the scope of physical therapist practice, the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) has concluded that DN is an appropriate intervention for physical therapists to provide to their patients.3,5,7 As of July 2024, according to the APTA, all but four states within the United States allow the practice of DN.8 Most states require continuing education or the ability to demonstrate competency beyond entry-level physical therapist education. Continuing education courses are variable in length, ranging between two and four days, including specifics on needling techniques, contraindications, and emergency preparation and response.1,9

According to Halle et al., published articles regarding DN increased from seven new references in 2009 to 51 new references in 2014.10 A recent review of the term ‘dry needling’ in the national PubMed database, as of December 2024, yielded a cumulative total of 1,189 articles, with approximately 90% of those articles being published in a ten-year span (2014-2024). While considerable research has been published over the past decade, the focus has primarily investigated the efficacy of DN to alleviate pain related to certain neuromusculoskeletal conditions, such as trigger points and muscle adhesions.2 Because DN is a developing technique within physical therapist practice, it is important to examine all facets of the intervention, including adverse events. An adverse event can be defined as “any ill-effect, no matter how small, that is unintended and non-therapeutic.”11 (p.85) Although the efficacy of DN continues to be explored and appears positive, understanding the potential adverse events and the overall patient experience is imperative to consider when recommending DN in future clinical practice.

Witt et al. published a prospective observational study with 229,230 patients, evaluating the safety of acupuncture needling. Although this study was based on patients’ self-reporting the adverse events post-technique, it evaluated acupuncture needling, not DN which differs from traditional acupuncture.12 Acupuncture aims to target meridian points (specific places that correspond to various body organs and function).13 DN involves the penetration of needles into specific trigger points in muscles or other soft tissue without regard for meridian points and performed by trained healthcare providers.1–3,14 Adverse events have been thoroughly investigated in relation to acupuncture but are severely limited in those related to DN.

Brady et al. and Boyce et al. studied adverse events of DN and reported similar findings: both reported bleeding and bruising as the most commonly experienced adverse events from DN.3,15 However, both studies were greatly limited by the fact that physical therapists, not patients, were surveyed on patient adverse events. This is problematic as many adverse events are likely not experienced until after leaving the clinic and may go unreported to the therapist. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate patients’ perspectives of self-reported adverse events and clinical outcomes from DN within the first 24 hours following the technique. In obtaining this point of view, a gap in literature will be filled, and physical therapists will be able to provide more detailed information to their patients regarding expectations following performance of the technique.

METHODS

Study Design

A cross-sectional retrospective study utilizing an electronic survey was conducted to determine patient experiences post DN, approved by Western Kentucky University Institutional Review Board (IRB #22-240).

Participants

From April to May 2022, individuals were recruited via word of mouth, social media, and university-wide emails to complete an electronic survey via Qualtrics (© 2020 Qualtrics LLC. All rights reserved). Eligible participants included those individuals >18 years of age and who had received DN in the prior three months by a licensed physical therapist. The initial recruitment email included the survey link in which the first two questions of the survey were based on the inclusion criteria and signing of the informed consent. Participants were directly asked if DN was performed within the last three months and by a physical therapist. If qualifications were met and informed consent signed, the individual could continue with the survey. The goal was not to isolate one session of DN, but to analyze adverse events over the course of receiving DN.

Survey Design

The survey consisted of 25 total items, with three main sections: knowledge and previous experience of DN, location and perceived effects of DN, and participant demographics. The first section on knowledge and prior experience of DN had six questions. The perceived effects section had nine questions. It focused on the region of the body in which DN was used, the adverse events, and clinical outcomes experienced. For each region of the body that the participant selected, the questions related to adverse events and clinical outcomes were repeated. This strategy allowed the authors to independently analyze the responses as they pertained to each region of the body. Adverse events were categorized as either localized (e.g., pain, soreness, bruising) or generalized (e.g., shortness of breath, fatigue, fever), while the clinical outcomes included pain, strength, gait and mobility. The third section was participant demographics, which included seven questions and was utilized to capture general characteristics of the respondent. In an effort to understand the patient’s feelings on whether the modality’s benefits outweigh the potential adverse events experienced, an additional question about whether they would recommend the modality was included.

Pilot testing of the survey was completed by a convenience sampling of eight individuals: four physical therapists who perform DN, one physical therapist assistant, and three non-healthcare providers who have received DN previously. The survey was modified to improve clarity and content per feedback provided. There has not been any study of reliability and validity of the survey, which was created by the authors (Appendix A).

Data analysis

Survey data were downloaded from Qualtrics (© 2020 Qualtrics LLC. All rights reserved) and exported into SPSS Statistics Version (Version 27, IBM Statistics, Armonk, NY). Participant demographics and individual item responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

Demographics and DN overview questions

One hundred twenty-three participants, representing a total of 221 body regions, completed the survey. Incomplete responses were not included in the final analyses. Participant demographics are listed in Table 1.

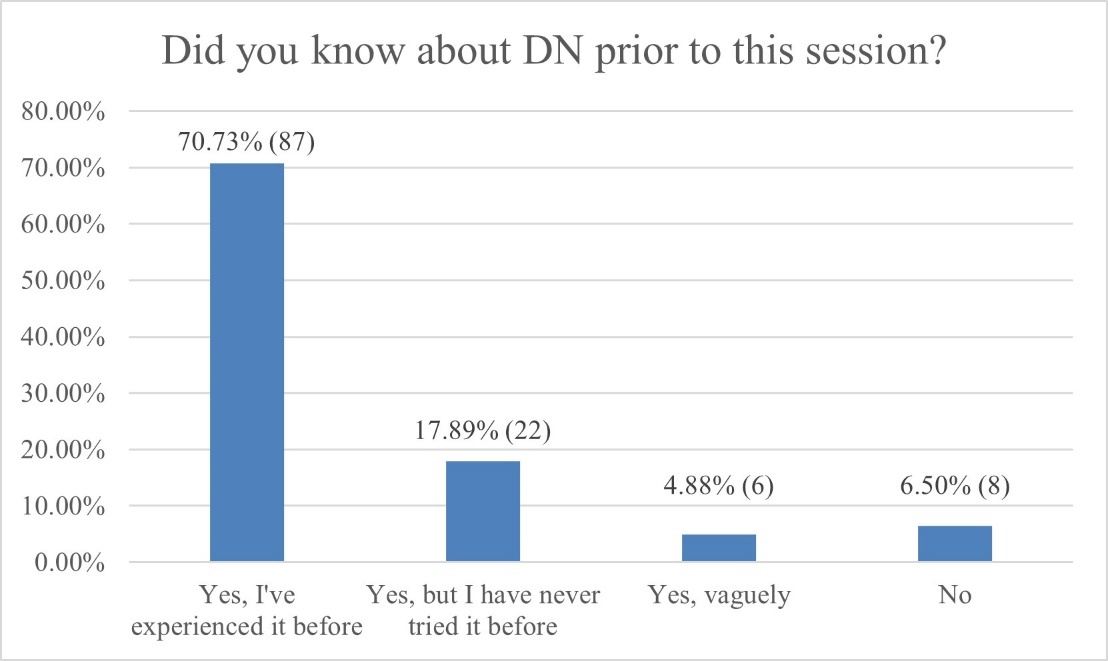

Most respondents had prior knowledge of DN and had experienced multiple sessions of the technique in the prior three months (Figures 1 and 2).

Body Region Frequency, Adverse Events, and Outcomes

Respondents selected which body regions were treated using DN by a physical therapist. The respondent was able to select more than one region, if applicable, and were not asked to clarify if it was one session or multiple sessions. With 123 participants, a total number of 221 body regions were identified as having been treated using DN. Of all the regions, the shoulder (n=46, 20.8%) and lumbar spine (n=34, 15.4%) were the most commonly reported locations for DN (Table 2).

Respondents reported the type of adverse events experienced locally at the site and generalized adverse events within the body for each region selected. Possible localized adverse events included soreness, cramping, increased localized pain, bleeding, bruising, and none (no side effects). There was an option to select ‘other’ and provide an open-ended response. Among all body regions, soreness was the most commonly reported localized adverse event (n=115, 52%), followed by pain (n=73, 33%) (Table 3, Figure 3). Possible generalized adverse events included weakness, shortness of breath, headache, fever, body aches, fatigue, and none (no side effects). There was an option to select ‘other’ and provide an open-ended response. Among all body regions, no generalized adverse events (n=131, 59.3%) were most often reported, followed by reports of fatigue (n=48, 21.7%) and headache (n=34, 15.4%) (Table 4, Figure 4).

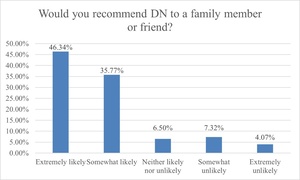

In addition to reporting adverse events, respondents selected if a change was noticeable in key clinical outcomes including pain, strength, gait, and mobility for each body region selected. Amongst all body regions, 73.8% reported improved pain; 38.5% reported improved strength; 46.2% reported improved gait; and 70.6% reported improved mobility (Table 5). Despite the presence of adverse events, 82.1% (n=101) respondents reported that they would recommend DN to a family member or friend (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to describe patients’ perspectives regarding the adverse events and effects (pain, strength, gait, mobility) of DN as it pertains to specific body regions. By reporting this point of view, physical therapists can be equipped to provide more detailed information to their patients regarding expectations with the technique. At least one localized event was reported in over 80% of the cases while at least one generalized adverse event was reported 40%. The most commonly reported adverse events were soreness and pain (localized) and fatigue and headache (generalized). Following the technique of DN, improved pain occurred in 73.8% of the selected body regions; improved strength occurred in 38.5%; improved gait in 46.2%; and improved mobility in 70.6%.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study examining patients’ perspectives on DN, which poses challenges for direct comparison in prior studies. Previously published work most often cites pain, bruising, and bleeding as the most common adverse events when gathering information from the physical therapist.2,3,14 In the current study, increased pain at the site of DN, at 33%, was the second most reported localized adverse event, whereas bruising and bleeding were less commonly reported (five and six out of the seven options). Headaches were reported 15% amongst the generalized adverse events, which is higher than outcomes reported by Gattie et al. who described 2%.2 This discrepancy may be, at least in part, due to the fact that in the present study, 32.4% of the time in which headaches were selected as an adverse event, the body region receiving DN was the shoulder or neck/face. However, previous studies did not collect data on the body regions that received DN for direct comparison. Collectively, these findings suggest a disconnect between clinicians and patients on the experience of headaches post DN.

Adverse events are reported differently throughout the research, and there is not a single database that tracks all events associated with DN.1 Events have been reported as uncategorized/categorized, minor/major, mild/significant/serious, or common/uncommon/rare.1,3,5,15 Minor events, as determined by Boyce et al. include bleeding, bruising, pain during, pain after, aggravated symptoms, drowsiness, feeling faint, headache, and nausea. Major events included prolonged symptoms aggravation, fainting, forgotten needles, flu like symptoms, infection, excessive bleeding, lower limb weakness, and numbness.3 Others have described mild events that can include bleeding, bruising, pain during and after, dizziness, temporary symptoms aggravation, nausea, sweating, and fatigue.1,5 Significant events can include prolonged pain, excessive bleeding or bruising, nerve injury, headache, vomiting, forgotten needles, seizures, extreme fatigue, and severe emotional reactions.1,5 This demonstrates that there is not one set way to categorize adverse events, and overlap exists amongst these descriptive categories. In the current study, the adverse events were termed ‘side effects’ and categorized as local to the site of DN compared to generalized in the body to improve clarity to the respondent as a potential non-healthcare provider.

In 2024, Ickert et al. surveyed physical therapists on which adverse events should be included in an informed consent for the patient to sign prior to DN.14 The consensus was skin irritation, neurological symptoms, fainting, increase of symptoms, bleeding, diaphoresis, fatigue, pain during/after, pneumothorax, soreness, bruising, dizziness, drowsiness, and superficial hematoma under skin. The most commonly reported adverse events from the current study are included in this consolidated list.14

A risk-to-benefit ratio should be considered when determining whether DN intervention ought to be used in the clinic. In the present study, despite the number of temporary adverse events experienced, 38.5-73.8% of the occurrences resulted in patient perceptions of improved pain, strength, gait, and/or mobility. The effectiveness of DN has been examined for different body regions over the last decade, with some conflicting evidence. Llamas-Ramos et al. found DN had similar results when compared to manual therapy in chronic neck pain regarding pain, function, and range of motion, but did show greater improved pain pressure sensitivity.16 A systematic review of the use of DN for those with neck pain symptoms found DN was more effective in the short term for pain intensity, but not pain pressure sensitivity.17 Range of motion and strength were improved in a study by Mousavi-Khatir et al. who investigated participants with cervicogenic headache.18 These results support the present study where patients perceived that DN led to improvement in pain, mobility, and strength.

A portion of literature discusses both objective and subjective improvements of gait following DN. In the current study, only the subjective (perceived) response was evaluated, in which improvement in gait was reported to by 46.2% of responses across all body regions. It is important to note, of those who reported worsening or no change to gait, an estimated 70% had DN applied to the upper extremity, which limits the interpretation of the current findings. In a study examining DN as an intervention in patients with multiple sclerosis, a single session of DN to the lower extremity did not show significant immediate objective changes on gait. However, the participants were surveyed at one week and four weeks post-DN and reported improved self-perceived walking capacity.19

Limitations

Respondents who had a positive or negative experience with DN may have been more likely to take the survey, leading to the possibility of selection bias. In addition, the survey was distributed within a local area of the U.S. via emails and social media platforms. General demographics of the individual that utilizes social media may have skewed the sample population, and potentially, social media algorithms may have limited distribution. Together, these factors may limit generalizability. An area of future research would be to survey an older population. Investigating a variety of age ranges could provide insight into the perceptions of DN across the lifespan, or the likelihood of adverse events as it relates to an individual’s comorbidities. Non-validated survey tools, while necessary for this study, may have resulted in unintended bias. Furthermore, the authors understand that having DN performed on multiple body regions and across potentially multiple sessions may have impacted accuracy of the reporting and ability to identify which region improved outcomes or caused generalized adverse events. Future studies should examine clinician’s pre-DN education with self-reported patient outcomes. Additionally, surveying individuals at different time points following the intervention could identify different results.

CONCLUSION

The results of the current study indicate that from the patient’s perspective, local adverse events (i.e., soreness, pain) appear to be more frequent in comparison to those generalized to the entire body. However, regardless of the presence of adverse events, 82.1% of respondents would recommend DN to a family member or friend. Physical therapists and practitioners who utilize DN have a responsibility to communicate the range of adverse events that may occur within the first 24 hours following the intervention. This study will better equip the clinician to do that with data directly from the patient’s personal experiences.