INTRODUCTION

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury and reconstruction represent a significant problem, with approximately 200,000 - 300,000 ACL reconstructions performed annually.1 While a considerable amount of time and resources have been invested into developing return-to-sports (RTS) criteria, there is currently no agreed-upon universal testing standard. With reinjury rates as high as 30% within younger populations,2,3 clinicians seek innovative, objective, and easily accessible means of improving clinical decision-making. The vertical countermovement jump (CMJ) is a functional task widely utilized as a performance test and exercise during sports training and rehabilitation to improve lower extremity power, coordination, neuromuscular control, and endurance.4,5 The CMJ has been associated with sprint kinematics, sprint times, and muscle strength in healthy athletes6,7 and may be used during recovery after injuries, such as ACL reconstruction (ACLR), to evaluate lower limb muscle function, providing valuable insight into various concentric and eccentric muscle performance constructs.8,9 Research has demonstrated that performance deficits in CMJ exist within the post-ACLR population and relate to isolated measures of isokinetic knee muscle function,10 supporting the high ecological validity of using the CMJ as both a training method and evaluative criteria for recovery after ACLR.9,11–13 To this point, the inclusion of vertical jump tests, such as the CMJ, are commonly suggested as important assessments to help determine an athlete’s RTS readiness.12

Evaluation of performance during the CMJ typically includes assessment of vertical jump height; however, alternative metrics, such as vertical ground reaction force (GRF), rate of force development (RFD), and impulse, may offer additional information to improve clinical decision-making.14,15 These more advanced measures provide deeper insight into how effectively athletes can produce or dissipate the forces needed to tolerate the rapid movements required for sports activities. Several studies have identified impaired surgical limb RFD in athletes after ACLR.16–18 Consequently, some experts recommend the inclusion of RFD as a component of an ACLR test battery to inform RTS clinical decision-making.9,18

Historically, assessing GRF, RFD, and impulse during the CMJ has been challenging due to high equipment costs, technical complexity, the need for specialized expertise, and the significant time and effort needed to process and interpret the data. However, recent technological advances have produced less expensive, user-friendly alternatives that provide outcome measures in real-time. The proliferation of these devices has improved clinicians’ access to more comprehensive objective measures of functional performance. These clinically focused force plates may lack the precision of research-grade devices and are limited to measuring vertically oriented force vectors. However, their proprietary algorithms handle data analysis and interpretation, eliminating the need for specialized expertise to process the data and calculate relevant measures. While this development is promising, there is limited evidence supporting the concurrent validity of the range of variables provided by these devices, particularly from studies conducted independently of the manufacturers.19–22 Additionally, to the authors’ knowledge, no studies have evaluated validity specific to youth athletes. Population-specific validation is important as previously identified differences in task performance and variability in biomechanics between children and adults may impact measurement accuracy.23 Therefore, it is crucial to understand the congruence of clinical grade devices and laboratory-based equipment in evaluating CMJ performance in youth athletes to ensure accurate clinical applications and confidence in RTS decisions. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare the concurrent validity of specific performance metrics obtained during a CMJ jump between a clinical grade force plate system and a laboratory grade system. The authors hypothesized that differences would exist in CMJ metrics between clinical grade and research grade force plates.

METHODS

Participants

A convenience sample of youth basketball athletes between the ages of 11 and 15 were asked to participate in a one-time testing session involving performing a CMJ on two force plate systems. Testing was conducted at a large youth basketball camp hosted by the Mavs Academy, attended by youth basketball players from rural and urban areas in the southern United States. Participants were excluded if they had experienced a musculoskeletal injury within the prior three months or had been diagnosed with an orthopedic condition that would limit their ability to perform the required jump tasks. Participation in the study was voluntary, with all participants providing informed assent, and parental consent was obtained before participation. During the movement assessment, participants wore comfortable attire and personal athletic footwear. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Texas Southwestern.

Procedures

Testing was conducted in a large basketball arena. Participants were asked to perform a CMJ while standing on each of the force plate systems. Two practice jumps were permitted before the participant performed a single countermovement jump on the VALD ForceDecks system (VALD Performance, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia) followed by a single countermovement jump on two AMTI force plates (Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., Watertown, MA, USA). A countdown was given for each CMJ task, which required participants to stand with their hands on their hips and jump as high as possible without a preparatory step. To ensure data quality, investigators observed the athlete’s movement quality during each trial to verify that each jump complied with the predetermined parameters described in the literature.24–26 In the event of specific errors of failing to achieve flight phase, removing hands from hips, or failing to land completely on the force plates, the trial was discounted, and the subject was asked to repeat the trial. Participant warm-up was not standardized as CMJ testing was part of a larger combine-style event with other functional testing stations.

Data Analysis

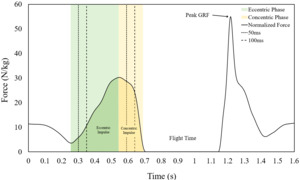

Force data from both plates were collected at 1000 Hz. Using a custom MATLAB code (MATLAB 2020b, Natick, MA, USA), raw force data from each device was plotted across time (Figure 1). Body mass (kg) was extracted from force plate data during a quiet standing period before the initiation of movement and was used to normalize the force data across participants (i.e., force data presented as N/kg). Jump height (cm) was computed using a flight time equation well documented in prior literature,19,27 and peak GRF was extracted from the force data across the entire jump. The onset of the concentric phase was determined by a relative maximum force defined as the maximum GRF between the beginning of data collection and the end of propulsion when the ground reaction phase fell below 2% of body mass.28 The onset of the eccentric phase was determined via a relative minimum force as defined by the minimum GRF between the beginning of data collection and the beginning of the concentric phase.28 For each phase, the total RFD was computed by taking the slope of the force-time curve across each phase. Subsequently, RFD was computed across the first 50ms and 100ms following the onset of each phase, as reported in past literature.8,29,30 Additionally, impulse for each phase was calculated using a two-frame moving window trapezoidal rule method.31 The area under the curve between each set of time points was calculated and added together.

Means and standard deviations were computed for all continuous variables (age, body mass, and CMJ metrics). Shapiro-Wilk tests of normality were significant; thus, non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to identify differences between devices in jump height, peak GRF, RFD, and impulse variables. Percent difference was computed between devices ((VALD – AMTI) / AMTI) *100 for each jump height, peak GRF, RFD, and impulse metric. All statistical tests were performed in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0, Armonk, NY, USA), and the significance level was set to 0.05. Additionally, Spearman correlations identified significant relationships between the force plate systems, and were defined as weak (r ≤ 0.35), moderate (r = 0.36-0.67), or strong (r ≥ 0.68).32

RESULTS

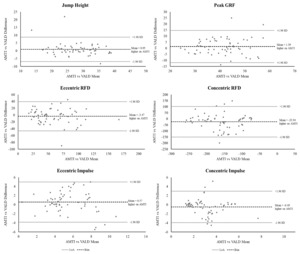

Sixty youth basketball athletes (24 female, 13.5 ± 1.0 years, 61.6 ± 15.0 kg) were included for analysis. Percent differences and statistical comparisons between VALD and AMTI-derived metrics are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences noted between devices for jump height (VALD: 27.37 ± 6.85 cm, AMTI: 28.32 ± 5.99 cm, p = 0.059) and peak GRF (VALD: 40.28 ± 8.44 N/kg, AMTI: 41.67 ± 9.03 N/kg, p = 0.160). While no statistical differences in eccentric RFD were noted, there were significant differences between devices in eccentric and concentric impulse, with a percent difference of nearly 10% and over 17%, respectively. Correlation results identified statistically significant relationships among all variables. While statistically significant, the correlations were strong for only three of the ten CMJ metrics (jump height, peak GRF, and total eccentric RFD; Table 2). Bland Altman plots further demonstrate the differences in CMJ measurements and illustrate observed agreement between the two devices (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to evaluate the concurrent validity of clinical grade and research grade force plates in analyzing CMJ performance in youth athletes across several commonly used metrics. The data partially supported the authors’ hypothesis. The measurements of jump height, peak GRF, and eccentric RFD peak demonstrated good agreement between devices; however, other measures of jump performance, including eccentric and concentric impulse, were only moderately to poorly correlated and differed significantly between devices, indicating that these isolated metrics obtained from the different systems cannot be used interchangeably.

The CMJ is a simple, widely used plyometric training exercise and standardized test of athleticism that has been a mainstay of athletic performance testing and rehabilitation training for decades.4,5 While the exclusive use of vertical jump height can be useful, experts are now encouraging clinicians to incorporate more complex and nuanced measures of performance that potentially offer a greater understanding of an athlete’s muscular capacity to produce movement.9 Despite passing traditional RTS criteria, measures derived from force plate technology such as GRF, RFD, and impulse are commonly altered in patients following ACLR and may be associated with reduced sports performance or an increased reinjury risk.12,14,33

The RFD measures how quickly a muscle can produce (i.e., concentric) or attenuate (i.e., eccentric) forces within a given time and has become an attractive metric to evaluate functional muscle performance in sports performance training and ACLR rehabilitation.34 While RFD assesses how quickly force is produced, impulse measures the total force produced over a given period. Analyzing the RFD and impulse offers clinicians more insight into nuances of muscle performance and may functionally translate to sports activities more directly than isolated measures of maximal muscle strength (i.e., isokinetic peak torque). These measures of muscle performance can provide clinicians with more information about an athlete’s readiness to withstand the demands of sports activities. This is especially important in athletes participating in sports with a high prevalence of ACL injuries, as they often require rapid muscle contractions to accelerate or decelerate movement. Research has demonstrated that deficits in RFD and impulse may persist within the operative limb after ACLR despite the resolution of isometric peak torque force production and vertical jump height.16 Traditional RTS test batteries following ACLR have shown inconsistent effectiveness in reducing ipsilateral or contralateral risk of re-injury.35 This has led to the consideration of incorporating additional measures, such as RFD, into more comprehensive RTS assessments.8,16,36

The proliferation of clinical grade force plates, such as the VALD ForceDecks utilized in this study, represent an attractive tool for clinicians assisting athletes in rehabilitation and performance environments. These force plates offer clinicians an affordable, user-friendly option for complex muscle performance and function assessments. Collings et al.21 recently published a comprehensive assessment of the reliability and validity of the VALD ForceDecks system in a sample of 16 college-aged individuals (mean age 25.9) across several functional performance tests. The authors assessed the concurrent validity of this system for the countermovement jump (CMJ) by comparing it to laboratory force plates across 168 performance metrics. They found good to excellent reliability in 142 of the 168 parameters (84.5%) and strong validity in 157 of the 168 parameters (93.4%), including jump height, peak GRF, RFD, and impulse. However, the findings should be interpreted cautiously as the force plates manufacturing company, VALD, funded the research, presenting a potential financial conflict of interest. Interestingly, their findings do not fully align with the results of the current study. While both studies found excellent reliability in jump height and peak GRF, the current data highlights limitations regarding the validity of impulse and eccentric RFD metrics. The differences in mean values and weak correlations observed in this study suggest that the measurements provided by these two devices are unrelated and differ significantly. Therefore, the data should be interpreted cautiously when comparing CMJ impulse and eccentric RFD data between research grade force plates and the clinically oriented force plates used in this study, as the devices are not interchangeable. Clinical providers should be aware that impulse and RFD values data comparisons may differ from published research, typically captured using laboratory-grade force plates. While differences in subject demographics or testing methodology may explain some of the disagreement in findings, future research should continue to attempt to clarify the measurement properties of VALD ForceDecks and other clinical grade force plates to help guide the clinical translation and interpretation of measurement values provided by newer technologies. This is particularly true for impulse measures as not only were the mean differences between devices significantly different, but correlation analysis was poor, indicating the measurements from the two devices diverged in magnitude and direction.

Differences in precision between clinically oriented measurement tools and laboratory-based devices are common. For example, previous research has identified that clinic-friendly hand-held dynamometers used to evaluate quadriceps strength may overestimate limb symmetry values compared to isokinetic dynamometry, a more expensive testing paradigm typically reserved for more specialized clinics or laboratory-based settings.37 The high agreement between clinical grade and laboratory grade devices for jump height, peak GRF, and total eccentric RFD is encouraging and demonstrates that clinicians can feel confident that these CMJ data metrics are accurate and can be compared to other values obtained utilizing laboratory-grade equipment. Thus, clinicians using the VALD system to evaluate an athlete’s CMJ test jump height or GRF can reasonably compare these values to published research to support informed clinical decisions but use caution when interpreting values related to impulse and RFD.

This study is not without limitations. A single jump was captured per device, which the authors acknowledge increases the chance of variability as there may be inconsistencies with participant performance that would be revealed over the course of several jumps. Additionally, subjects performed the CMJ on each system individually. This methodological decision was based on limitations described in previous work with alternative designs to reduce the potential loss of data granularity and precision in performing a CMJ across both devices simultaneously (i.e., stacking one on top of the other).21 However, this decision may have introduced some errors in the results of this study due to potential variability in CMJ performance between CMJ trials. While this possibility exists, the authors incorporated additional steps to ensure consistent inter-trial CMJ performance. This methodology is supported by prior research demonstrating low variability in CMJ performance between trials.38,39 The moderate to high correlations observed for some outcome measures (i.e., jump height) between the two systems suggest that trial-to-trial variability may not have significantly impacted the comparisons between force plates. In contrast, outcome measures with weaker correlations may be more sensitive to such variability. Due to the established differences between commercially available automated force-time curve analysis software and custom software,40 the current study downloaded all raw data from VALD and AMTI force plates to uniformly calculate all variables. While this is a strength of the current study design, not obtaining the measures from the VALD-specific software may have impacted results. Finally, the results of this study are specific to the two force plate systems utilized and may not be generalizable to other clinical or laboratory-grade force plate systems or alternative measures of CMJ performance.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate VALD ForceDecks provide comparable measurements to laboratory grade force plates for jump height, peak GRF, and eccentric RFD in youth athletes. Clinicians should use caution when comparing data related to RFD and impulse between these different systems due to limited agreement and low correlations. Future research is required to better understand the relationship between laboratory and clinical measurement devices and potentially curate separate guidelines for CMJ performance specific to each measurement device.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.