INTRODUCTION

Abdominal muscles play an important role in trunk neuromuscular control in both an anticipatory and reflexive manner.1 Volitional preemptive abdominal contraction (VPAC) is an established method to dynamically stabilize the spine2–4 during functional and sports activities5,6 while assisting in reducing risk for injury.2,5–8 Two specific VPAC approaches have been used to actively contract the abdominals, including the abdominal drawing in maneuver (ADIM)9,10 and abdominal bracing maneuver (ABM).2,11 The ADIM volitionally stabilizes the spine via segmental trunk muscle activation, such as transversus abdominis and internal oblique (IO)3,12,13 while the ABM stabilizes through global muscle activation such as rectus abdominis, external oblique (EO) and erector spinae.11,12 While previous studies have examined both VPAC strategies in a non-distracting environment,2–13 ABM performance while a participant is cognitively distracted must be explored. While both VPAC strategies have been predominately studied in a non-distracting environment, no previous studies have examined ABM performance while a participant is cognitively distracted.

Aoki et al. investigated automatic trunk muscle contraction responses during lower extremity (LE) movements.14 These investigators speculated that the central nervous system manages active spine stabilization through abdominal and multifidus muscle co-contraction in anticipation of the reactive forces produced by limb movement. However, the participants were seated and were instructed to perform active single leg raises in response to a sudden destabilizing force. Moreover, the study did not assess volitional abdominal activation during a functional LE task.

Lower extremity functional movements can be influenced by one’s ability to dynamically control the trunk. Saki et al. suggested that greater trunk stabilization improved neuromuscular function of athletes with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.15 Hooper et al. demonstrated that VPAC during an LE reaching task resulted in increased trunk and pelvic muscle activation allowing improved LE kinematics during a forward single leg squat.5 Furthermore, VPAC performance may serve as a factor that reduces injury risk during dynamic functional tasks. Haddas et al. demonstrated that VPAC leads to increased spine stability during an asymmetric lift, which could be beneficial to reduce re-injury in individuals with recurrent low back pain.6 Addit(nally, VPAC use has been demonstrated to decrease the effects of muscle fatigue and improve onset of LE muscle contraction during a drop-jump landing in individuals with low back pain (LBP), thus reducing the risk of injury.16 Lynch et al. demonstrated that VPAC can effectively increase abdominal activation without altering postural control in healthy individuals, notably while performing a loaded squat without a stabilization belt.2

The Y-Balance Test (YBT) is a functional measurement tool that assesses unipedal balance control in response to perturbation through opposite LE movement.17,18 The YBT has demonstrated reliability,19 cost-effectiveness, and validity20 for assessing dynamic balance and postural control.19 However, it is not known if cognitive distraction may influence a healthy participant’s VPAC ability during this dynamic LE reaching task.

Executive cognitive distraction (ECD, or “Stroop Effect”) is an auditory or visual diversion which can influence neuromuscular trunk control during functional activities.21–23

Xiao et al. reported that individuals with LBP exhibited abnormal postural control, which was influenced by the nature and complexity of dual task demands.24 Jones et al. measured trunk electromyography (EMG) in healthy individuals seated while performing rapid LE movements with and without cognitive distraction tasks.25 The addition of the cognitive task delayed and reduced LE EMG activation but had little impact on trunk muscle activation patterns. These results suggested a decoupling of voluntary and postural control mechanisms, favoring a reflexive motor pattern over an anticipatory pattern when dealing with dual tasks. Using an auditory Stroop protocol, the current study attempted to investigate trunk muscle activation patterns when influenced by ECD on a demanding unipedal LE reaching task.

The researchers questioned if ECD could influence a participant’s ability to sustain an ABM during any of the three YBT directions. Kublawi et al found that a Stroop task did not negatively affect a healthy participants ability to sustain a VPAC during quiet standing or loaded forward reach.9 Additionally, the researchers considered how a combination of VPAC and ECD would affect LE reach distances during any of the three YBT directions. Previous studies have shown that VPAC performance improves functional activity performance and efficiency of LE movements.5,6,26

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of ECD on the ability to sustain an ABM during a dynamic unipedal functional task. Specifically, this study aimed to determine: (1) if ECD influences the external oblique (EO) or internal oblique (IO) on the side of the stance LE preferentially over the EO or IO on the moving LE while performing the YBT, and (2) if ECD affects the YBT reach distance during the ABM versus No–ABM conditions.

The authors hypothesized that ECD would decrease a participant’s ability to sustain an ABM during all YBT directions. In addition, researchers hypothesized that ECD would decrease reach distance produced during a dynamic unipedal functional task performance. Based on Garcia et al, researchers hypothesized that ECD use would significantly interact with ABM status during dynamic LE reaching for each dependent variable measurement outcome.27

METHODS

Research Design and Variables

This study incorporated a within-participants repeated measures design. For VPAC option, researchers chose the ABM. The ABM variable included two levels: No ABM and ABM. Similarly, the ECD variable presented with two levels: No-Stroop and Yes-Stroop. The dependent variables were moving and stance IO EMG root mean squared (RMS) values, moving and stance EO EMG RMS values, as well as the YBT reach distances (anterior [ANT], posteromedial [PM], and posterolateral [PL]).

Sampling and Participants

Healthy male and female participants, between 20 and 41 years of age, were recruited from two sources: (1) the student, faculty, and staff population at Texas Tech University Health Science Center (TTUCHC), and (2) the acquaintances of the investigators from the general Lubbock, TX area. Investigators attempted to equalize male and female participants to maintain sample distribution. A sample size of 30 participants was determined to obtain a desired α= 0.05, power of 80% (1-β= 0.80), with an estimated effect size of f=0.25.28 Participants were informed of risks and benefits and then signed a written informed consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects at TTUHSC (IRB#L16-184). Table 1 provides inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Instrumentation and Materials

Surface EMG (sEMG) recordings of bilateral EO and IO muscles were collected through a telemetry EMG system (TeleMyo 900, Noraxon USA, Scottsdale, AZ) using dual Ag/AgCL snap sEMG electrodes to examine muscle activation patterns associated with VPAC. The EMG input impedance was >10, with a common mode rejection ratio of >100 dB and baseline noise <1 μV RMS. The EMG data were sampled at 1000 Hz.

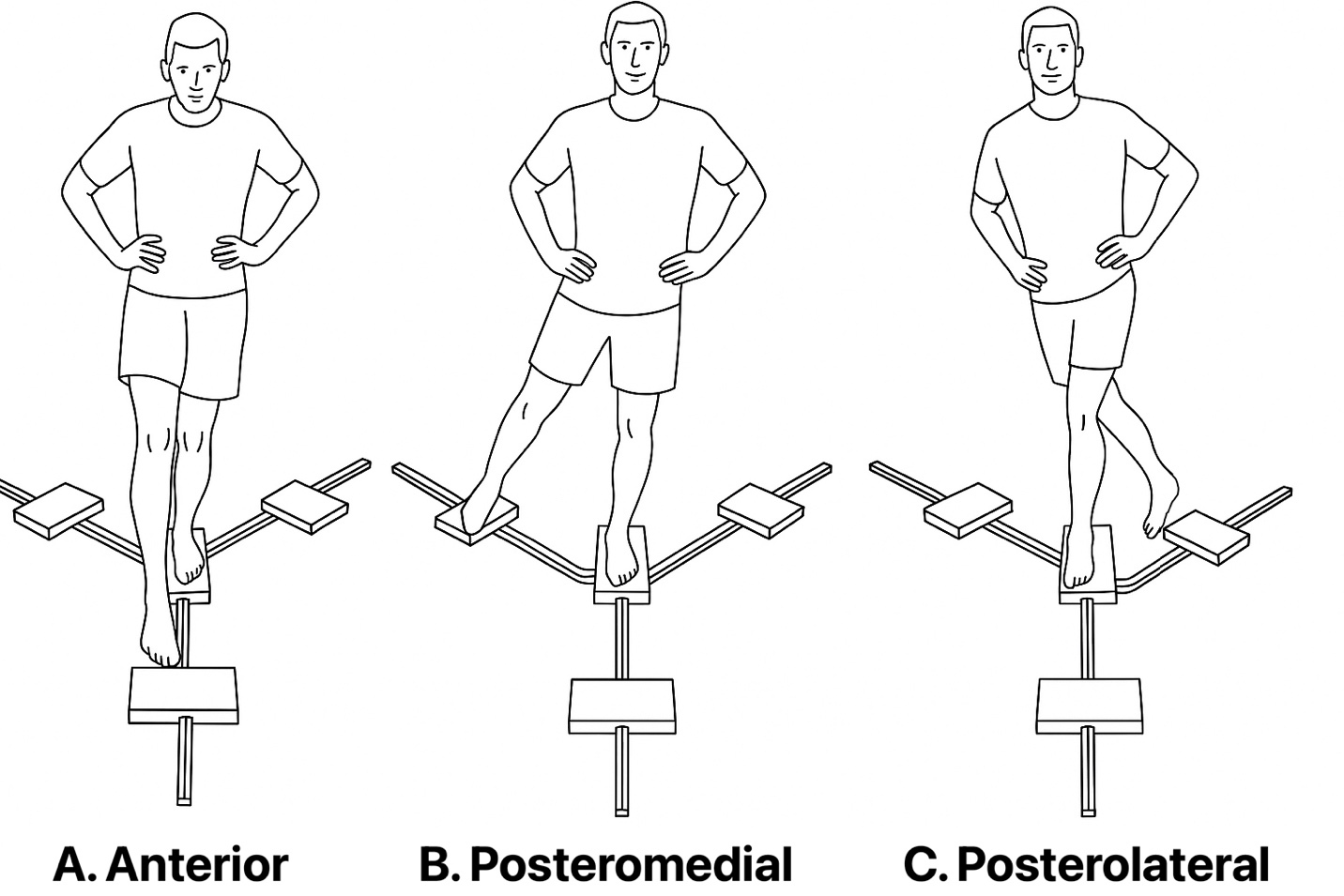

The YBT procedure was completed using the YBT kit (www.functionalmovements.com, Danville, VA), which is comprised of a central grid and three slide indicator boxes (Figure 1). Secondary author (AD) with greater than five years marker placement experience, positioned three-dimensional reflective markers on each YBT slider. Using an eight camera Vicon Nexus motion capture system (Vicon, Oxford, England), a motion recording was made to represent participant trial completion. Established in a previous investigation, the auditory Stroop program was utilized using a laptop computer in sync with noise cancelling headphones.9,29

Preparatory Procedures

Participants were educated on VPAC performance, YBT performance, and Stroop description. Next, participants were weighed (pounds), measured for height (inches), leg length measured,30 and dominant leg determined. The dominant limb was determined by asking the participant, “which leg do you use for kicking a ball?”.31 The verbal command used for No-VPAC was, “continue your normal breathing”.11 “Place the web space of the thumbs on your respective iliac crests. Now make your lower trunk wider. Hold this contraction and continue to breathe” was used for ABM.26 After the co-investigator PS with greater than 25 years of PT experience confirmed proper ABM activation via tactile cueing for trunk widening, each participant performed six practice contractions for 10 seconds.9

For YBT testing, each subject performed all trials in a computerized random order to decrease fatigue and training effects. Each subject was instructed to stand on their dominant LE, reach forward with the opposite leg and push the indicator box without losing balance, finished by returning to bipedal stance. Each participant was instructed to maintain each hand’s webspace on its respective iliac crest, while performing the reach procedure at their own natural speed. Participants were instructed that any error performing the YBT activity would result in trial re-performance. Five YBT practice trials were performed with an inter-trial 10 second rest to reduce a learning effect.

Electrode Placement and Signal Normalization

After skin cleaning with disposable alcohol wipes (and allowing it to vaporize), sEMG electrodes were placed on the participants’ bilateral IO and EO accordingly to previous studies.14,32 In addition, an elastic abdominal binder was used to support electrode placement but not hinder body movement. After visual confirmation of proper sEMG signal during a practice contraction, baseline submaximal voluntary contraction (SubMVC) testing in supine was performed by having each participant raise both legs five cm off the plinth for three seconds.33 To assist with future comparisons using LBP individuals, SubMVCs were used as they demonstrate improved reliability over maximum voluntary contractions (MVC).34 Moreover, SubMVC was found to be more sensitive versus MVC when assessing lower-level muscle activity.35 Finally, SubMVC reference tests may be more consistent with the actual contractions necessary for functional spine segmental stability. Stifter et al. discovered that a low MVC abdominal muscle contraction was sufficient to stabilize the spine during daily activity tasks, thus supporting this study’s use of SubMVC for normalization.36

ECD (Stroop) Application

Each Stroop combination was drafted from a database of 10 stereotypically masculine terms, 10 stereotypically feminine terms, 10 stereotypically gender-neutral terms, 10 male names, and 10 female names (Table 2).9

Each condition consisted of five terms with a two-second separation between terms.9,37 Although not allowed to practice preserving its novelty,29 the Stroop instructions were to, “maintain your thenar web space on each iliac crest, raise your left fifth digit in response to a masculine term, right fifth digit for a feminine term, and no response for gender-neutral terms.” This auditory-to-motor dual-task response requires brain specific activation of error detection38 and control of conflict management.39–41 The challenging nature of auditory Stroop with appropriate time intervals implies construct validity for auditory ECD.

Data Collection Procedures

Each participant completed two repetitions of each of the two strategy conditions (YES ABM and No ABM), along with YES Stroop and NO Stroop conditions, in all three YBT directions (ANT, PL, and PM) for a total of 12 trials (Table 3).

To reduce fatigue effects, a 30-second rest between each trial was incorporated. Trial conditions were computer randomized before data collection. For YBT reach distances, mean values were normalized for each condition using the following formula42:

Normalized LE YBT Reach Distance= Mean ExcursionLimb LengthX 100

DATA REDUCTION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSES

All EMG signals were analyzed in Matlab (The MathWorks, Inc). Signals were band-pass filtered at 20-400 Hz with a fourth order, no-pass, zero-phase-lag Butterworth filter. For the SubMVC normalization trials, the average RMS of the final three seconds of the three trials were calculated. All EMG data were reported as a percentage of this value. The RMS amplitudes of the filtered EMG data for each muscle over the entire trial was analyzed, and average muscle activity from the beginning of the trial to the point of maximum reach was calculated.

Descriptive statistics were calculated to include the mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Data were tested for normality using a Shapiro-Wilk test and through evaluating skewness and kurtosis (acceptable values falling between -2.0 and +2.0).

A 2 (ABM) X 2 (ECD, or “Stroop”) repeated measures ANOVA was used to identify significant interactions between, as well as main effects for, each dependent variable during each YBT direction. Tukey’s post-hoc comparisons were used for identifying significant differences.

RESULTS

Thirty subjects participated (26.4 ± 5.1 years, height 66.9 ± 3.3 in, weight 156.5 ± 31.9 lb., and BMI 25.0 ± 4.3kg/m2) (18 female, 12 male). Table 4 presents muscle contraction amplitudes for EO and IO during each ABM condition on the stance and reach sides, represented by RMS EMG % SubMVC Means. Outliers greater than 2.2 standard deviations were removed (5% of total Ant YBT trial means; 6% of total PM YBT trial means; 5% of total PL YBT trial means).43 For YBT reach distance data, only one outlier was found greater than 2.2 standard deviations (<1%).

There was a main effect for ABM in all YBT directions Table 5 (p<0.05). A main effect was also found for both IO and EO muscle groups (p<0.05). All participants under these conditions were able to maintain the ABM with or without ECD while reaching in all three directions of the YBT (p<0.05).

Regarding reach distances, there was a main effect for Stroop in the PM direction (F[1, 29]= 8.718, p= 0.006). No Stroop main effects were found in the PL and Ant directions (p>0.149 and p>0.878), respectively (Table 6).

In addition, a Stroop main effect on ABM with stance IO and moving EO in the PM direction (F=[1, 29]= 9.703, p=0.004 and F=[1, 29= 25.082, p<0.001) was revealed. Finally, a main effect was found for the moving limb EO in the ANT direction (F=[1, 29]= 5.022, p<0.033). No Stroop to ABM interaction was found (p>.05).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of ECD on healthy participants’ ability to sustain an ABM while performing a dynamic unipedal functional task. We studied the abdominal muscle activation patterns as a response to the ECD, as well as YBT reach distances. When confronted with an auditory to motor distracted task, researchers’ main interest was determining this level of distraction. At the time of writing, this article was the first to examine Stroop effects on ABM during a dynamic LE reach maneuver. The healthy study participants were able to maintain a supportive trunk muscle response when exposed to a distractive event while performing a unipedal reaching task in multiple directions.

The spinal protective benefits of either VPAC strategy have been examined extensively in previous research,5,26,44,45 as well as VPAC’s influence on LE movements.6,26 With regards to ABM performance, previous studies have focused on a loaded forward reach,9,10 UE movements,46 or a vertical drop landing.8,16,47 This study’s findings were in agreement with Kublawi et al. who found that individuals could sustain a VPAC while distracted during an upper extremity reach task performance.9 In contrast to Kublawi et al. the current study tasks were more complex and perturbing in nature because the participants had to reach with their LE in various directions outside their base of support.9 Participants were able to sustain a protective VPAC under these more stringent conditions. When compared to vertical jump landing research, the current study findings concur that ability to sustain an ABM improved abdominal muscle activation, regardless the presence of ECD. Contrary to previous studies on VPAC effect on LE movement during stair ambulation, no effect was discovered in the ANT direction, the most similar YBT movement to ascending stairs. The study results demonstrate the importance of abdominal activation during functional activities, even when cognitively distracted. These findings demonstrate the complex interaction ECD imparts on a unipedal functional activity.

Regarding YBT reach distances, only the PM direction was affected by ECD. When analyzing the motor task, both the PL and PM directions require greater demand on the trunk and LEs when compared to the ANT direction.5,48,49 When reaching posterior to the base of support, Hooper et al. found that individuals suffering from LBP reach less in the PM and PL directions compared to ANT when compared with healthy controls.5 Greater hip abductor strength,48 and hip range of motion49 are required when performing the YBT PM and PL directions. Hooper et al.5 surmised that because ANT reach was within the field of forward vision, reaching in an anterior direction during the YBT was easier to push the YBT indicator box versus the PL and PM directions. The increased muscular, visual, and balance demands involved when performing the posterior directions could explain the enhanced distracted Stroop effect in the PM direction, since all trial conditions were computer randomly ordered.

A Stroop distraction must sufficiently challenge the participant’s ability to perform a functional task. Shanbehzadeh et al. reported that when dual-tasking a postural event and Stroop distraction, subjects with chronic LBP reduced their postural sway area, as well as increased their Stroop reaction time as the difficulty of the dual-task reached moderate levels of difficulty.50 Li et al. noted that when using gender-related incongruent terms as the Stroop distraction, a proper gradient must be implemented to fully appreciate the distraction effects.51 The current study used an audible task in addition to a secondary motor task revealing a 15% participant Stroop error ratio. This finding, along with the main effect for Stroop on the PM reach direction, suggests that the current Stroop protocol sufficiently provided a challenging cognitive distraction,

Although the current study used an ABM, previous studies have examined ADIM with similar results.2,10,11,52 Previous ABM studies reported increased spinal compression,4,50,53 reduced LE movement during a lifting activity,54 and increased lumbar spine stiffness during spinal perturbation.4,53 As a result of dual-task proficiency, study participants were able to sustain the ABM effectively even while cognitively distracted. In addition, since reach distances were only affected by Stroop in the PM direction, it is possible that changing the VPAC strategy choice to an ADIM could have demonstrated a more pronounced effect.

LIMITATIONS

As previously noted, there was a two-second gap between each subsequent distractive term. The LE reaching movement speed was participant dependent with some subjects performing the movement quickly, suggesting ease with the activity. As a result, these subjects only performed the LE reaching task during the first or second Stroop terms. This resulted in the subjects performing the final 3-4 terms while in the bipedal stance. Future studies should standardize the timing of the LE reaching movement to permit completion of all five terms during the LE reaching sequence and allow for full cognitive distraction effects.

Another study limitation was the use of SubMVC reference contractions for the percent amplitude data used in this comparison. This approach resulted in a high degree of variability in the normalized EMG values. Franco-López et al found trunk muscle SubMVC more reliable than MVC with between-day comparisons.34 Although the choice to use SubMVC was for future comparisons on LBP individuals, the current healthy participants may have experienced an increased variability because some subjects were more athletic than others.

Although attempts were made to maintain equal numbers of male and female participants, the sample was predominately female with a mean age of 26 years. A younger, healthy sample may have more experience with multi-tasking cognitive functions, thus not demonstrating a difference in ability performing a ABM or LE reaching task when being cognitively distracted.55 Donath et al found that when compared to younger adults, older adults exhibited two to six-fold higher levels of relative muscle activity of the trunk and LEs when performing postural balance tasks.56 To fully appreciate the impact of age, future studies should examine the effects of Stroop on a unipedal LE reaching task comparing various age groups.

FUTURE RESEARCH

With the growing evidence on concussive attention span deficits, future research should focus on the effects of cognitive distraction on individuals rehabilitating from hernia repair,57spinal or hip surgery, or suffering from a recent or previous concussion.58 Since subjects with LBP can demonstrate decreased YBT reach distances, the effect ECD has on motor performance on this population should be studied.59 Finally, since fear-avoidance can interfere with motor tasks, future research should explore its effect from ECD.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that healthy participants were able to perform an ABM during LE reaching tasks, even when cognitively distracted, although YBT reach distance was affected by Stroop distraction in the PM direction. Overall, the results suggest healthy participants should be able to use an ABM while performing unipedal activities that incorporate dynamic balance. Future research is required to determine the effect cognitive distraction has during an athletic or activity of daily living.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author would like to thank his family for their support