Background

The elbow is the most frequently injured body part in professional baseball players. Injuries to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) are both the most frequently seen and result in the largest number of lost playing days. In fact, from 2016 to 2024 there has been a 29% increase in the number of UCL injuries in professional baseball players and approximately 25% of all Major League Baseball (MLB) pitchers have undergone UCL surgery.1

In the 18-year span between 2006 to 2024 there was a 250% increase in professional baseball players placed on the disabled list for musculoskeletal injuries with a corresponding 300% increase in the total number of disabled days experienced. In 2024, over one billion dollars was spent on medical care of all musculoskeletal injuries for injured Major League Baseball players.2 At the Andrews Sports Medicine & Orthopaedic Center in Birmingham, Alabama we have experienced a significant increase in the number of UCL injuries and surgeries in the past 15 years.3 The increase in UCL elbow injuries has not been limited to professional baseball athletes. Likewise, there has been a similar increase in UCL injuries in youth, adolescent, and college baseball players.

Differentiating between a UCL and flexor-pronator injury is often difficult because the symptoms both produce pain in the medial elbow, and they frequently occur together. The purpose of this commentary is to describe the clinical thought process used to assist in making an accurate differential diagnosis between a UCL sprain and a flexor-pronator strain. The clinical examination description that follows is not meant to be comprehensive but instead will focus on the elements germane to differentiation between UCL and flexor-pronator issues.

Clinical Examination

As with any clinical examination, a thorough, stepwise, careful process is essential to accurately distinguish between UCL and flexor-pronator injury. This is particularly true in the examination of overhead throwing athletes. The examination begins with a detailed subjective history which not only includes a detailed description of the injury timeline but addresses several baseball specific questions:.

-

Did symptoms occur with a single pitch or develop over time?

-

Was a “pop” experienced?

-

Are there any nerve symptoms? Especially in the 4 & 5th finger?

-

At what phase of the throw do you have pain?

-

Where is the location of the elbow pain?

-

Is there a specific pitch-type that causes symptoms?

-

What pitches or throws cause your symptoms?

-

Does intensity of the throw influence your pain?

-

Are you currently able to pitch with the injury?

-

Has there been any impact on velocity or accuracy?

-

Have you had this problem before? If so, please explain.

-

Have you had any shoulder, neck or spine injuries, pain or surgeries?

-

Does hitting or other sports cause elbow symptoms?

-

Does lifting weights cause elbow symptoms?

Additionally, previous history of elbow and/or shoulder injuries and surgeries are essential for context and clarity. UCL injuries are often associated with a sudden “pop” coupled with an inability to continue throwing, while flexor-pronator injuries can have an acute onset of pain or a chronic onset with a gradual decline in performance.

Observation of posture, scapular position and the presence of scapular dyskinesis can all provide insights into throwing arm injury patterns. Active and passive range of motion of the shoulder, elbow, forearm, and wrist should all be assessed. Specifically, glenohumeral active range of motion (AROM) should be screened for elevation, abduction, and combined internal rotation and external rotation. Passive range of motion (PROM) of the throwing arm is best assessed in the supine position with particular emphasis placed on evaluating shoulder total range of rotational motion measuring external rotation and internal rotation at 90 degrees of shoulder abduction and elbow flexion. When comparing the total envelope of combined motion (total rotational motion), external rotation and internal rotation side to side for asymmetries more than + 5 degrees,4 Shoulder flexion should be assessed to ensure unrestricted/full passive motion, because as little as a 5 degrees loss of shoulder flexion has been linked to increased stress on the elbow.5 Elbow extension, forearm pronation, and wrist extension should all be assessed for any restrictions or limitations. Frequently asymptomatic pitchers will exhibit a loss of elbow extension, Wright et al6 reported a 7.9 degree loss of extension and a 5.5 degree loss of elbow flexion of throwing elbow passive range of motion compared to the non-throwing elbow.

Consistent with the motion assessment, a strength exam should include the entire upper extremity. Close attention should be paid to the scapular musculature, posterior rotator cuff, triceps, and flexor-pronators of the forearm. Assessing grip strength is also important as a painful weak grip may be an indicator of flexor-pronator involvement. Use of a handheld and grip dynamometer is important to provide objectivitestrength measurements.

A thorough neurovascular exam should be performed to rule out the presence of thoracic outlet syndrome and ulnar nerve neuritis, both of which are common in overhead athletes. Ulnar nerve symptoms are frequently present with UCL sprains and not present in flexor/pronator strains.

Special testing is the crux of making an accurate differential diagnosis between these two conditions. In the authors’ clinical exam process three tests are incorporated for assessing UCL integrity and two for flexor pronator involvement. This commentary introduces the prone valgus stress test, a modification of valgus stress testing for UCL integrity, and the “Thinker” test for flexor tendon involvement. These have proven to be invaluable in clarification between UCL and flexor pronator involvement. Further research is needed to determine validity of this test.

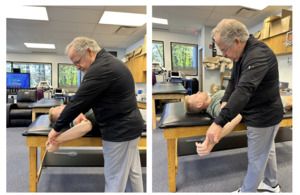

UCL integrity assessment is made using a combination of the prone valgus stress test (Figure 1, Supplemental Video 1), the moving valgus test7 (Figure 2, Supplemental Video 2), and the milking maneuver8 (Figure 3, Supplemental Video 3). Although the seated or supine valgus stress test is often utilized by clinicians, the authors prefer the prone valgus stress test. The test is performed with the athlete in a prone position, using the table to support the upper arm and minimize rotation of the arm during examination. The senior author (KEW) prefers this test over seated or supine testing because prone with the shoulder abducted to 90 degrees and fully internally rotated minimizes humeral rotation during testing. This position provides greater isolation of pure valgus stress by controlling the potential rotational substitution of the humerus often experienced in traditional valgus stress testing.

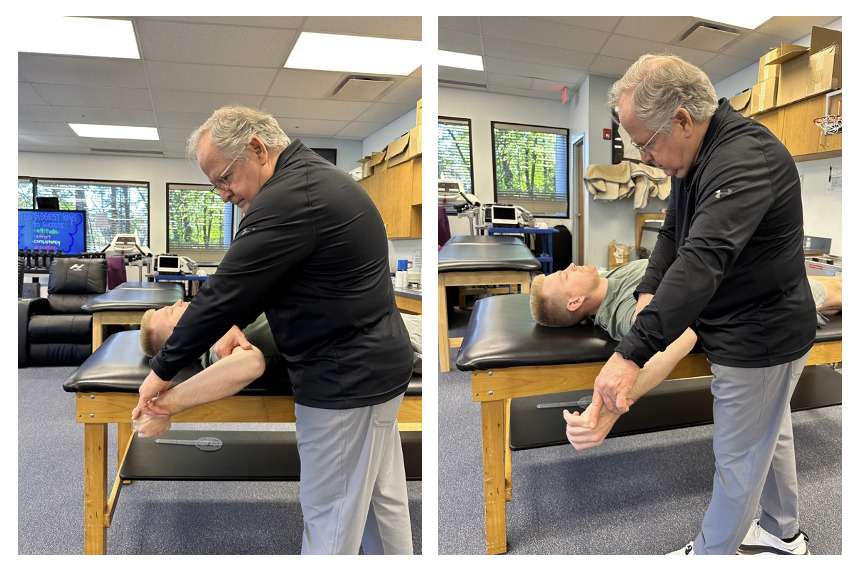

The moving valgus test is performed by applying a valgus force to a fully flexed elbow while the arm is in abduction and external rotation. The elbow is then gradually extended by the examiner. The test is positive if there is medial elbow pain, particularly between 120° and 70° of flexion. The milking maneuver is performed by the examiner grasping and pulling the patient’s thumb while the patient’s elbow is flexed beyond 90 degrees and the forearm is fully supinated, creating a valgus stress on the elbow which stresses the UCL. The moving valgus test and milking maneuver assist in determining if the UCL is symptomatic, whereas the valgus stress test determines the degree of laxity. Laxity is often seen in asymptomatic overhead throwing athletes, small degree of valgus laxity is a common finding.

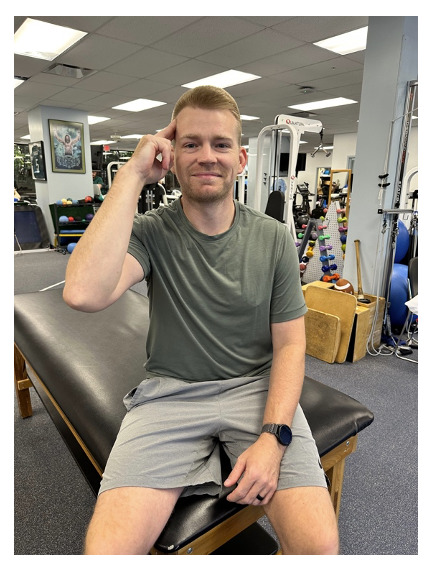

To assess for flexor pronator involvement, a combination of the Thinker’s Sign (Figure 4, Supplemental Video 4) and resisted testing of the flexor-pronator group (Figure 5) are utilized. The thinker test is a maneuver that grew out of a professional baseball pitcher demonstrating what exactly reproduced his symptoms to the senior author (KEW) several years ago. The athlete reported that when shampooing his hair and pressing into his scalp he felt pain. Shortly thereafter, the authors of this article started utilizing what has been termed the thinker’s sign, asking the athlete to press their index and third fingers into the side of their head. The presence of pain during this maneuver is regarded as a positive test. Resisted flexor-pronator testing is simply performed by manually resisting wrist flexion and forearm pronation as in a manual muscle test.

Palpation can provide clarity when discrete localization of symptoms can be achieved. However, care must be taken to isolate the UCL and flexor-pronator mass individually. UCL palpation is typically posterior and distal to the medial epicondyle, along the course of the ligament. Palpation of the flexor-pronator mass is localized slightly anterior and distal to the medial epicondyle, at the common flexor tendon origin. The authors prefer to palpate the UCL with the athlete supine and with external rotation of the shoulder at 90 degrees of abduction (Figure 6).

To further determine specific involvement other tests such as radiographs are used to evaluate for potential osseous involvement such as stress fractures, osteochondritis dessicans lesions, or avulsion fractures of the sublime tubercle, as well as the buildup of calcium deposits within the ligament in chronic cases of UCL injury. The usual radiographic series utilized to assess the osseous structures of the elbow are listed in Table 1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) are the gold standard for soft tissue assessment with MRA being more sensitive in the identification of partial tears9(Figure 7). Nonenhanced MRI is 57% to 79% sensitive and 100% specific for UCL tears, whereas magnetic resonance arthrogram with saline or gadolinium is 97% sensitive and 100% specific.10

Diagnostic ultrasound imaging also serves as one of the diagnostic tools for evaluating the UCL for injuries.11 The anterior band of the UCL is identified originating at the medial epicondyle and inserting in the sublime tubercle. An intact UCL has homogenously hyperechoic collagen fibers tapering down towards the sublime tubercle (Figure 8). In the case of UCL pathology, any of the following may be seen: 1. Cortical irregularity, mainly at the UCL origin on the medial epicondyle, 2. Heterogenous echogenicity with a mixture of hyperechoic and hypoechoic collagen fibers, 3. A thickened UCL ligament compared to the contralateral asymptomatic side, and/or 4. Anechoic defect in the ligament, compatible with the disruption of the collagen fibers due to a partial or a complete UCL tear (Figure 9). Additionally, the UCL may be evaluated using a dynamic stress test during ultrasound imaging to identify joint laxity associated with a partial or complete UCL tear.12

Making the Differential Diagnosis

Arriving at an accurate differential diagnosis between elbow UCL and flexor-pronator injuries involves a compilation of seven categories of clinical information. These categories include pain location, mechanism of injury, pain with throwing, instability, physical exam testing, imaging, and associated symptoms.

Pinpoint tenderness directly over the UCL, located just below the medial epicondyle indicates ligamentous involvement, while tenderness slightly more anterior and distal to the medial epicondyle, along the belly of the forearm musculature is indicative of flexor-pronator injury. UCL injury is often associated with an acute “pop” during a specific throw or gradually from repetitive valgus stress, while an acute muscle tear of the flexor-pronator complex occurs during powerful eccentric contraction produced in acceleration but can also be chronic in nature due to repetitive overuse. Both conditions can produce pain during the late cocking and arm acceleration phases of the throwing motion.

A positive finding on valgus stress testing indicates UCL laxity and possible injury, while a stable non-painful elbow on stress testing with pain during the thinker maneuver and on resisted wrist flexion and forearm pronation is more indicative of flexor-pronator involvement. The moving valgus test indicates a painful UCL and suggests and injury to the ligament. Palpable tenderness localized to the muscle belly, distal to the medial epicondyle is in line with flexor-pronator involvement. Diagnostic testing with X-ray, MRI, MRA or ultrasound can further confirm soft tissue status and partial tears. Numbness or tingling in the ring and little fingers may occur due to ulnar nerve irritation, as the nerve runs close to the UCL. Neuropathy is less common in flexor-pronator injuries unless a large muscle tear or significant swelling is present.

Conclusions

Elbow injuries are common in overhead throwing sports and their frequency is on the rise. UCL and flexor-pronator injuries are two common pathologies seen in the throwing athlete. These can be difficult to distinguish on physical examination. A careful and systematic evaluation process which includes a detailed subjective history and systematic objective examination will assist the clinician in making an accurate differential diagnosis. The prone valgus stress test and the thinkers test can assist in an accurate diagnosis and help differentiate between UCL and flexor-pronator involvement. An accurate diagnosis is essential to establish an appropriate and successful rehabilitation program.

__normal_ucl_image__b)__proximal_tear_of_the_ucl_c)__distal_ucl_tear.png)

.___the_ligament_originates_at.png)

.___the_ligament_originat.png)

__normal_ucl_image__b)__proximal_tear_of_the_ucl_c)__distal_ucl_tear.png)

.___the_ligament_originates_at.png)

.___the_ligament_originat.png)