Introduction

Injuries to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) of the knee (also known as the fibular collateral ligament) are rare and constitute less than 2% of all knee injuries.1 It is not uncommon to injure the LCL in association with injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), and the posterior lateral corner.2

Anatomy of the Lateral Collateral Ligament

The LCL of the knee is located on the outside of the knee and is the primary restraint to a varus-directed force. The LCL acts as a secondary restraint to anterior and posterior tibial translation when the ACL and PCL are torn.3 This ligament is cord-shaped and extra-articular, connecting the femur to the fibula on the lateral side of the knee. Its normal length is between 5.5 to 7.1 cm.4 The femoral attachment is 1.4 mm proximal and 3.1 mm posterior to the lateral epicondyle, while the fibular attachment is at the fibular head, slightly posterior to its anterior margin.5

The most common mechanisms of LCL injury are a direct blow to the medial knee creating a varus stress, non-contact knee hyperextension, and non-contact varus stresses.6 LaPrade et al. have stated that a lateral joint opening of more than 2.7 mm suggests a LCL injury, and an opening that exceeds 4.0 mm is associated with a complete posterolateral corner injury.7 Sekiya et al. have reported that 10.5 mm or more of lateral joint opening will require posterolateral corner repair or reconstruction.8

The Role of Musculoskeletal Ultrasound in Ligament Evaluation

Advantages:

-

Real-Time Imaging: MSKUS allows dynamic evaluation of the LCL while the knee can be manipulated through the available range of motion.

-

High-Resolution Visualization: MSKUS provides detailed images of the LCL and the proximal and distal enthesis at the lateral epicondyle and the fibular head.

-

Accessibility and Cost-Effectiveness: MSKUS is portable, widely available, and less expensive than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Limitations:

-

Operator Dependency: MSKUS requires skill and experience for accurate interpretation of findings. The ability to sonograph musculoskeletal structures is influenced mainly by the operator, the availability of state-of-the-art equipment, and its technical considerations.

-

Artifacts and Shadows: Bone and calcifications may create image artifacts, requiring adjustments in probe positioning and frequency.

Sonographic Technique for Evaluating the Lateral Collateral Ligament

-

Probe Type: Because of the superficial nature of the LCL, a standard high-frequency, linear array transducer is typically used.

-

Patient Position: The patient is supine with the hip internally rotated and the knee in slight flexion (35-40 degrees). A bolster or towel roll can be placed under the medial knee for support. The probe is placed in either the short axis (SAX) or longitudinal axis (LAX), starting proximally near the lateral femoral epicondyle or distally at the fibular head.

-

Dynamic Assessment: A varus stress can be applied to the knee during ultrasound assessment to evaluate for lateral knee gapping or tension being placed through the LCL.

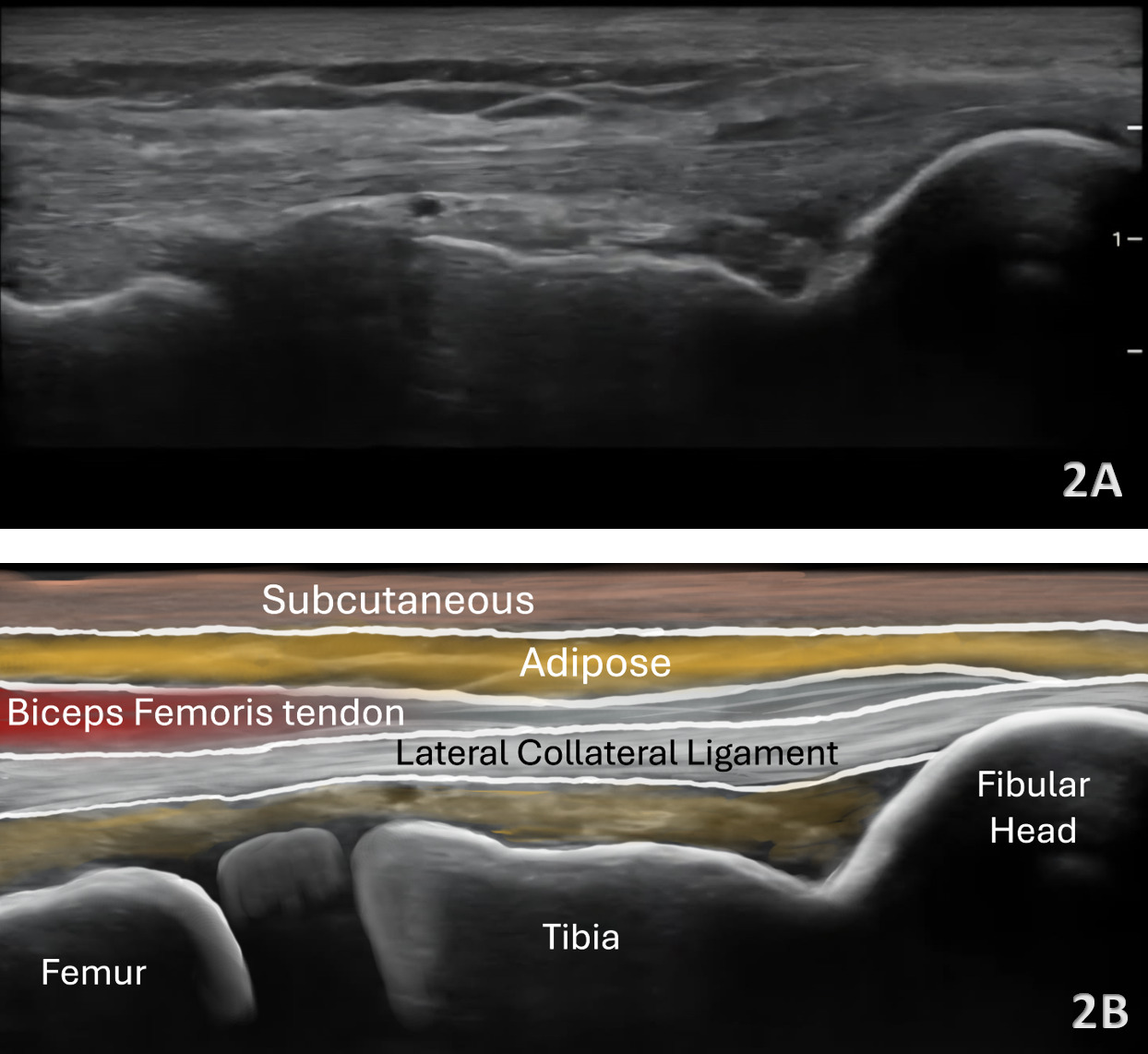

Normal Sonographic Appearance

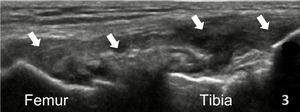

In the LAX view, depending on the probe width and size, one should start distally to visualize the hyperechoic reflection of the bony cortex of the fibular head distally and the cortex of the femoral epicondyle more proximally. If the depth is increased enough, you will also be able to visualize the bony reflection of the tibia directly below the fibular head. Usually, the LCL demonstrates a hyperechoic fibrillar pattern. The distal portion of the tendon may appear heterogeneous and thickened due to the bifurcating distal biceps femoris tendon that runs both superficial and deep to the LCL.9

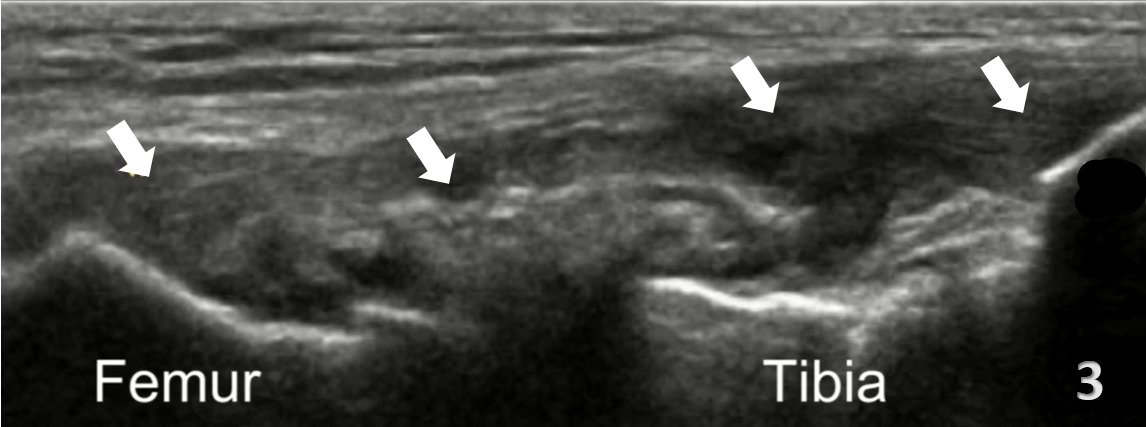

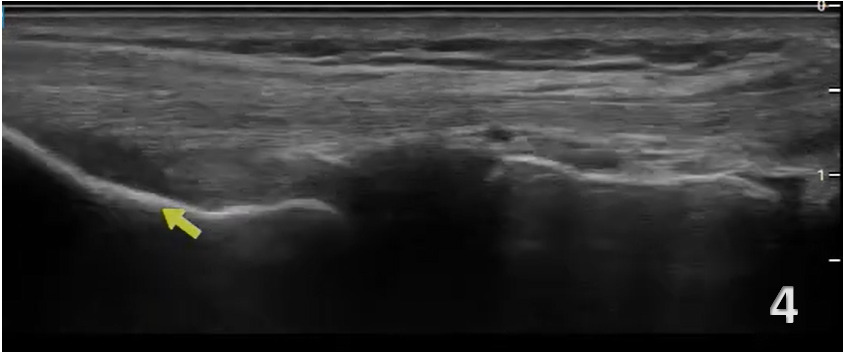

Pathologic Findings in Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury

-

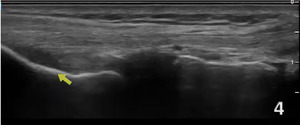

Disruption of fibrillar pattern of the ligament in partial tears and ruptures.

-

Associated joint effusion, presenting as anechoic regions.

-

Calcifications near the enthesis sites.

Clinical Implications for Rehabilitation Providers

MSKUS provides real-time feedback for rehabilitation professionals, facilitating early diagnosis and intervention. Key applications include:

-

Early Detection of Injury / Accurate Injury Grading: MSKUS can quickly differentiate between a strain and a more severe ligament rupture to help guide treatment planning. Rocha de Faria and colleagues have demonstrated the ability to use MSKUS with stress to grade ligament injuries.10 They found stress MSKUS to provide a low-cost, dynamic, and reproducible method for patient examinations.

-

Dynamic Functional Testing: Rehabilitation professionals can use MSKUS during physical therapy sessions to monitor recovery and assess ligament function dynamically. Serial MSKUS imaging aids in assessing ligament remodeling and readiness for rehabilitation progression.

-

Guided Interventions: Ultrasound imaging assists in needling intervention and precision-guided injections, such as corticosteroids for inflammation.

-

Patient Education: Real-time imaging serves as a visual aid to explain the nature of the injury and set realistic expectations for recovery.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite its advantages, MSKUS cannot entirely replace MRI for complex cases. Additionally, the expertise required for optimal imaging techniques limits its immediate adoption across all rehabilitation settings.

Conclusion

MSKUS is a valuable, dynamic, and cost-effective imaging modality for evaluating LCL injuries of the knee. Its ability to provide high-resolution, real-time visualization of ligament morphology, continuity, and surrounding soft-tissue structures makes it an excellent first-line tool in both acute and chronic settings. Ultrasound enables dynamic stress testing and comparison with the contralateral limb, providing diagnostic insights that standard static imaging techniques may not capture. While MRI remains the reference standard for complex or multi-ligamentous injuries, MSKUS offers distinct advantages in accessibility, rapid assessment, and guidance for therapeutic interventions such as injections or rehabilitation monitoring. Incorporating MSKUS into physical therapists’ clinical practice enhances diagnostic accuracy, supports timely decision-making, and ultimately improves patient outcomes in cases of suspected lateral collateral ligament injury.

.png)

.png)