INTRODUCTION

Anterior knee pain remains a frequent presenting concern in orthopaedic surgery and primary care clinics. Chronic fibrosis in the infrapatellar fat pad (Hoffa’s disease) is a rarely identified, yet treatable cause of anterior knee pain. The intraarticular, extra-synovial structure is highly vascularized, densely innervated and rich in the nociceptive substance-P.1–5 The role of the infrapatellar fat pad is incompletely understood, but thought to be multifactorial.6 The fat pad in its normal state contributes to shock absorption in the knee7 and can be observed to cause altered distribution of forces in the setting of fibrosis, which may play a role in the development of osteoarthritis.8 The infrapatellar fat pad is densely innervated with sensory nerve fibers implicating its role in anterior knee pain.9 In recent years, a growing understanding has emerged on the functionality of adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Specifically, the infrapatellar fat pad has been recognized to secrete adipokines,10 tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)11 and exists as a source of mesenchymal stromal cells.12 Conflicting evidence exists on the impact of resection of the infrapatellar fat pad on anterior knee pain. In a study of 1401 patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty, Moverly et al. demonstrated significantly increased patient reported outcome measures (Oxford Knee Score) in patients where the infrapatellar fat pad was preserved, as opposed to patients in whom the fat pad was resected.13 Conversely, Sekiya reported a marked improvement in anterior knee pain in patients with otherwise refractory knee pain after total knee arthroplasty who underwent arthroscopic infrapatellar fat pad resection.14

Fibrosis of the infrapatellar fat pad can be caused by traumatic injuries, or can arise due to post-surgical changes.15 The diagnosis of Hoffa’s disease can be made with a combination of history, physical exam, imaging, and diagnostic injection.2 The purpose of this case report is to describe two cases of anterior knee pain arising from fibrosis of the infrapatellar fat pad as identified on imaging and arthroscopy. The patients provided informed consent for publication of their cases.

CASE 1

A nineteen-year-old female patient presented to our clinic with a several year history of right worse than left anterolateral knee pain. She was an active collegiate-level cheerleader and described her pain as dull and achy, mostly in the anterior aspect of the knee, worse with prolonged activity and running, and relieved with rest. The pain was sufficiently severe to interfere with all recreational activities and activities of daily living. She denied any history of patellar instability events and denied any specific trauma or inciting event. She did however note that upon joining her collegiate cheerleading team, her practice surface changed to mats on wood, as opposed to the spring flooring she was previously accustomed to. She was seen by an outside institution, where she received a cortisone injection which offered temporary relief. At this same institution she underwent knee arthroscopy, plica debridement and marginal fat pad resection, which she stated gave her partial relief immediately following surgery. However, in retuning to running and tumbling she experienced recurrence of her symptoms. She also trialed a course of physical therapy, and activity modification without notable relief of symptoms.

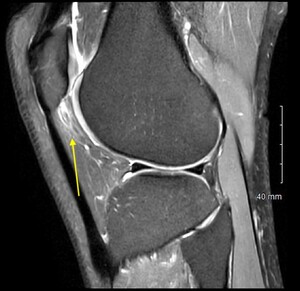

On exam she had pain to palpation of the anterolateral fat pat, with mild patellofemoral crepitus. Her range of motion was 0-130 degrees. Ligamentous exam was stable with full strength in quadriceps and hamstrings on manual muscle testing. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) demonstrated subtle thinning of the lateral patellar articular cartilage, fibrosis of the infrapatellar fat pad, and distension of the infrapatellar bursa (Figure 1). Otherwise, her MRI was unremarkable.

The decision was made to proceed with diagnostic fat pad injection in clinic. Under sterile conditions, using surface landmark technique the anterolateral fat pad was infiltrated with 15 mL of 1% lidocaine in the anterolateral soft spot, lateral to the patellar tendon. A 22-gauge hypodermic needle was directed centrally towards the intercondylar notch, advanced into the fat pad and slowly injected. To verify needle position within in the fat pad, slight resistance to infiltration was felt. If no resistance was encountered, the needle was felt to be intraarticular and was withdrawn until infiltration was met with resistance. Immediately following injection, the patient attempted treadmill running and reported a marked improvement in her symptoms. Based on her positive response to fat pad injection, and failure of previous interventions, the decision was made to proceed with arthroscopic fat pad excision.

Arthroscopy was initiated with a superolateral viewing portal, established based on previously described technique,16 to better visualize the extent of infrapatellar fat pad fibrosis. With the use of Metzenbaum scissors through standard anterolateral and anteromedial portals, the interval between the fat pad and patellar tendon was developed. This freed any adhesions between the patellar tendon and the underlying fat pad tissues to reduce the risk of patellar tendon injury during debridement.

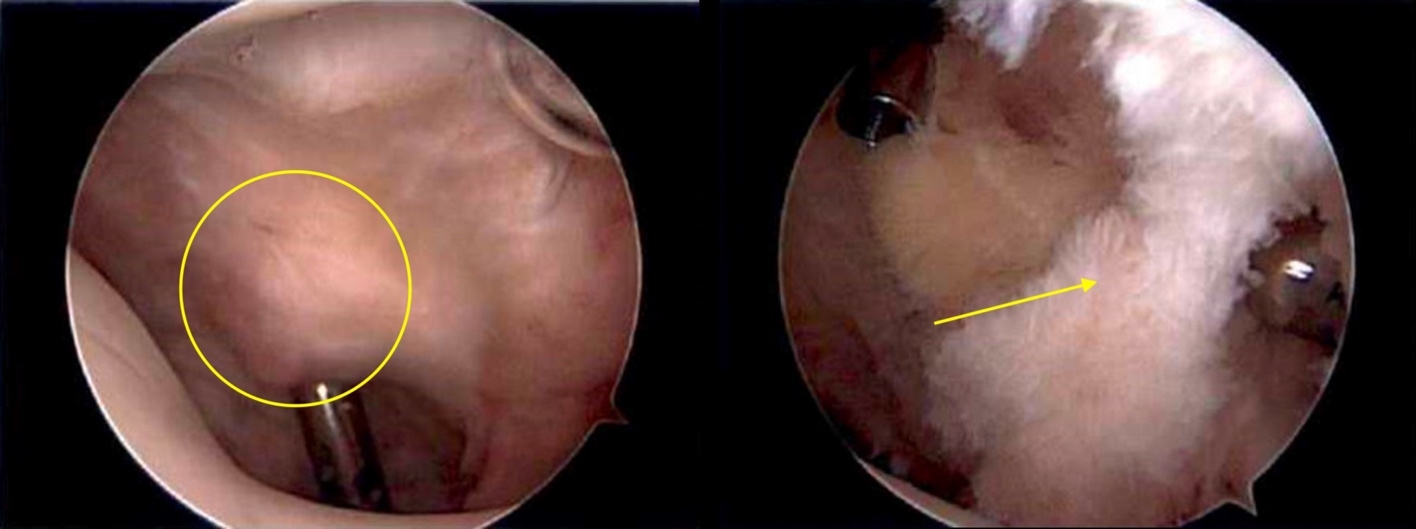

Through the superolateral portal view, a dense band of fibrotic scar tissue was identified on the posterior surface of the fat pad (Figure 2). With combination of basket punch and shaver, working through the anteroinferior portals, this scar tissue was resected in addition to approximately 70% of the remaining infrapatellar fat pad. A thin margin of fat pad was left in situ for protection of the overlying patellar tendon. The arthroscope was then placed in the anterolateral portal and a standard diagnostic arthroscopy was completed. The patient was noted to have some softening of the patellar cartilage in addition to a prominent lateral trochlear facet with relative medial trochlear facet hypoplasia. The remainder of her diagnostic exam was normal. Prior to exiting of the knee, tourniquet was released, and meticulous hemostasis of the remnant fat pad was established.

Post operatively, she was allowed to weight bear as tolerated and initiated a course of physical therapy focused on early re-establishment of range of motion and quadriceps activation. Jumping, weighted squats and other patellofemoral dominant exercises were avoided in the first three weeks post operatively and then gradually reintroduced. At most recent follow up one year post operatively, she reported that she experienced full resolution of symptoms and returned to full cheerleading and tumbling without any limitations.

CASE 2

A 27-year-old male presented to clinic complaining of bilateral anterior knee pain. He stated that he took up running in the preceding four years and since that time had experienced recurring anterior pain associated with running longer distances. He was seen by an outside orthopaedic surgeon, was given the diagnosis of patellar tendinitis and referred for physical therapy, a patellar tendon strap, and a topical anti-inflammatory. He did not experience relief with this course of treatment and sought another opinion. At presentation he stated that his pain had progressed to the point that he had symptoms with descending stairs and activities of daily living. He was unable to perform any recreational activities, though denied any catching, giving way or mechanical symptoms.

On physical exam he had no pain with patellar grind test but had pronounced pain to palpation of the infrapatellar fat pad. He had painless range of motion of 0-130 degrees and had no J sign and did not demonstrate patellar maltracking. Ligamentous exam was stable and neurovascular exam was intact. His MRI demonstrated hypertrophy and swelling of the infrapatellar fat pad (Figure 3). Given his history and imaging findings a diagnostic fat pad injection was chosen as the initial course of treatment. Following injection, the patient underwent treadmill running and noted a near complete resolution of symptoms and as such the decision was made to proceed with arthroscopic fat pad resection, starting with the more symptomatic right side.

Using the same technique described in Case 1,16 thick bands of fibrotic scar tissue were identified on the posterior surface of the markedly enlarged infrapatellar fat pad (Figure 4). Following resection of three-quarters of the fat pad, the arthroscope was then placed in the standard anterolateral portal to carry out further diagnostic exam.

In the first month post op, he noted resolution of his anterior knee pain and sought out a second arthroscopic fat pad resection on his contralateral knee. Eight weeks after his initial surgery, the left sided arthroscopic fat pad resection was performed, using the same technique. Again, he was found to have a markedly enlarged thickened and fibrotic fat pad. This was carefully resected, with the patellar tendon protected.

Post operatively he was allowed to weight bear as tolerated and was placed on a patellofemoral protection program with physical therapy with an emphasis on early range of motion and quadriceps activation. Post operatively, he reported marked improvement in symptoms compared to pre-op and continued to progress until three 3 months post operatively when he was released from follow up. He presented to the clinic four years post operatively with an unrelated traumatic injury to the right lateral knee but reported ongoing relief of his initial bilateral anterior knee pain.

DISCUSSION

The case reports illustrate the successful treatment of two patients who had anterior knee pain related to chronic fibrosis of the infrapatellar fat pad. With respect to the diagnosis of Hoffa’s disease, the authors have had excellent experience with the utilization of a diagnostic injection in the clinic setting. This is key to accurate diagnosis and subsequent treatment. After localizing the region of pain in the medial or lateral anterior soft spot, 10-15 mL of 1% lidocaine can be easily injected into the fat pad. Care is taken to inject the lidocaine slowly, as a rapid injection into the typically fibrotic fat pad can cause a painful reaction to the volume of the injection. The patient typically performs an activity in clinic (treadmill, stationary bike, or stair climbing) both before injection and post injection, after the onset of the local anesthetic. If there is a substantial improvement of the patient’s presenting symptoms, an arthroscopic fat pad debridement is suggested as it would be anticipated to provide similar relief.

In both of the presented cases, a superolateral viewing portal was utilized which the authors feel is absolutely crucial in adequately observing the infrapatellar fibrosis that would otherwise be missed with a 30-degree scope through standard inferior viewing portals. The complete description of this technique has been previously reported.16 In short, this technique protects the patellar tendon by creating an interval between the tendon and fat pad bluntly with the use of Metzenbaum scissors through the standard anterolateral and anteromedial arthroscopic portals. Additionally, it is important to adequately visualize the anterior horn of the medial and lateral menisci, as they could be at risk in this technique particularly with overzealous use of the arthroscopic shaver in the anterior interval. In the case of any subacute or chronic limitations in range of motion, additional post operative implementation of arthrofibrosis protocol is encouraged with particular focus on a gentle overpressure program.17

The findings of the present report are limited only to the two cases presented. Cause and effect cannot be assumed. Future studies would benefit from larger sample sizes and the inclusion of validated patient reported outcome measures, as well as detailed reporting of the physical therapy interventions used post resection.

CONCLUSION

As the understanding of the role of the infrapatellar fat pad grows, clinicians and patients alike stand to benefit from attention to this incompletely understood and complex anatomic structure. Further studies are required to completely elucidate the impact that the infrapatellar fat pad has on anterior knee pain as well as the results after resection. The presented patient cases demonstrate the frequently missed, yet treatable nature of infrapatellar fat pad fibrosis. Orthopaedic surgeons should be aware of this entity and consider utilization of local anesthetic injection for diagnostic purposes. Further, the importance of employing superolateral viewing portals cannot be understated to ensure adequate visualization for safe and sufficient fat pad resection. Rehabilitation providers can benefit from increased understanding of this commonly unrecognized diagnosis, as patients suffering from this condition are likely to be referred for physical therapy with otherwise limited structural pathology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.