INTRODUCTION

Trunk stabilization relies on the strength, motor control, and coordination of various structures working both passively and actively. Research shows that mechanical instability of the spine can occur with forces as low as 90 N, highlighting the need for strong core musculature to tolerate daily spinal loads that can exceed 1,000–3,000 N.1 Physical therapy interventions, including exercises like supine or quadruped alternating arm and leg movements and the double leg bridge, help maintain spinal stability by eliciting co-contraction of core and lower-extremity muscles.1

Foundational studies have shown that core endurance is a more accurate indicator of functional core strength and stability than maximal strength, especially in contexts relevant to injury prevention and physical performance.2–4 Core muscles, especially those in the deep stabilizing group (e.g., transverse abdominis and multifidus), are primarily postural muscles and are meant to sustain activity over time, supporting the body during daily activities and prolonged movements. Endurance testing offers a safe and effective measure of core performance across different age groups and fitness levels that can be used to establish parameters for treatment and goal setting in rehabilitation.5

Trunk and pelvic control have been recognized as indicators of fitness and injury risk, particularly in high-performance populations such as military personnel and athletes. The Single Leg Bridge (SLB) demonstrated strong predictive accuracy (AUC 0.756) for discriminating between soldiers with good and poor fitness on the Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT).6 Similarly, the SLB has shown to have predictive value for the determination of hamstring injury risk in Australian Rules Football players, with lower SLB hold times having a higher risk of sustaining hamstring injuries.7

Bridging exercises, like the SLB, are widely used in physical therapy to strengthen the core, hip, and thigh muscles, which improves trunk stability and function.1 Trunk stability is complex, requiring interventions that target various muscle groups. Core endurance tests have shown greater reliability for assessing stability compared to other measures such as flexibility or raw strength.8

The SLB is a unilateral version of the supine double leg bridge, shown to increase maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) in core muscles (rectus abdominis, external and internal obliques, and erector spinae) as well as in hip and thigh muscles (gluteus medius, gluteus maximus, and hamstrings).1,9 Gasibat et al. showed SLB typically elicits ~40–58% MVIC for gluteus maximus and gluteus medius.10 The SLB is particularly valuable for strengthening the gluteal muscles, including the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, as well as tensor fasciae latae.11 Strong gluteal muscles are crucial for injury prevention, proper gait mechanics, and athletic performance.12 High gluteal activation has been observed during the SLB, surpassing other gluteal strengthening exercises including double leg bridge or prone hip extension.13 Dysfunction in gluteal muscles is often associated with pain in the ankles, knees, hips and lower back, making gluteal strengthening essential in physical therapy.9 Additionally, the SLB enhances core stability, which can improve conditions like low back pain and lower-extremity dysfunction.9 While normative data exists for many core endurance assessments, such as the Sorensen test (240 seconds), side plank endurance test (72-94 seconds), prone bridge (52-77 seconds), and double leg bridge (152-188 seconds), there is a lack of established norms for the SLB.2,14,15 Further research to develop these norms would support the use of SLB as an effective measure of core stability. Additionally, establishing normative data creates a benchmark for injured individuals to work toward during recovery.

In addition to establishing normative values, it is important to examine the accuracy of clinician observation in determining SLB endurance performance. Visual assessment is the most common method used in clinical practice, yet it may be subject to variability and potential bias. Prior studies have shown that trained clinicians can achieve strong reliability when visually estimating joint motion or postural deviations, though accuracy may decline without standardized criteria.16 The emergence of digital tools, such as video-based goniometer applications, provides an opportunity to objectively detect deviations in joint position during endurance testing. Such applications have demonstrated acceptable validity, reliability, and usability for measuring joint angles in both healthy and clinical populations.17 Comparing visual estimation to app-based analysis can help determine whether clinicians can reliably identify the point of form loss using standardized criteria, or whether technology provides meaningful additional precision. This comparison has direct implications for the feasibility of the SLB as a clinical assessment tool across diverse practice settings.

The purpose of this study is two-fold: The first is to establish normative values for the SLB endurance test, which physical therapists can use as a reference for rehabilitation. The second is to evaluate whether visually assessing SLB form loss is as accurate as using an app with angle detection in measuring the total duration of SLB during endurance testing.

METHODS

Approval was obtained from the Georgia Southern University Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent before participation. Inclusion criteria required participants to be between 18 and 60 years old with no current back or lower-extremity pain. Exclusion criteria included known medical problems that would affect SLB performance, including history of chronic low back pain, disc related pathology, chronic hamstring/gluteal pain, poor health, current fracture, or lower extremity/low back injury in the prior six months.

Testing Procedures

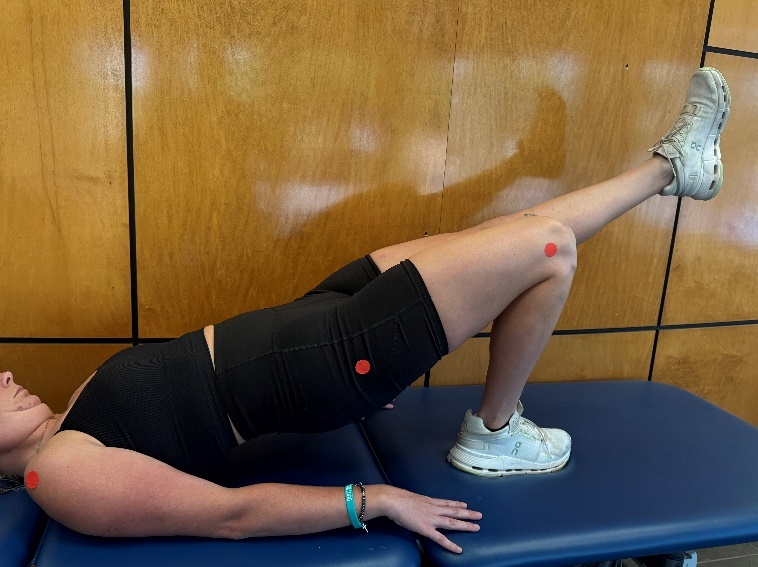

Participants completed a 5-minute active warm-up with light jogging, high knees, and forward leg kicks, followed by static stretching for hamstrings and lumbar rotation. After the warm-up, red adhesive markers were placed on bony landmarks (lateral acromion, greater trochanter, and lateral femoral condyle) for precise angle measurements. Each participant watched a video demonstrating the correct SLB form: hips parallel with shoulders and knees, foot positioned under the weight-bearing knee, pelvis level, and knees parallel (Figure 1). Participants laid supine on the testing table with knees bent.

Next, participants assumed a double leg bridge position for 5 seconds before lifting one foot to begin the SLB. The test duration was recorded, and participants were allowed one verbal correction if form momentarily wavered, addressing errors such as hip angle drift, changes in foot position, or loss of pelvic symmetry. If the participant was unable to regain correct alignment or if the deviation from the starting position visually exceeded what the researcher determined to be an approximate change of 10-degrees from the starting position, the researcher noted the time that the participant lost form. The test was terminated if the participant stated they were unable to continue to hold the position. A two-minute rest was given before repeating the test on the opposite leg. Both the dominant and nondominant leg data were used in analysis.

Instrumentation

The SLB test was analyzed using two methods: visual estimation and the “Angles – Video Goniometer” App (Angles App). For the visual estimation method, the SLB test was recorded using the camera app on an iPad 14 and the researcher manually timed the SLB using a stopwatch. The stopwatch was started by the researcher when the single leg was lifted off the table and stopped when the form was lost after no more than one verbal correction (as described above). For the second method, the Angles App was used to analyze video recordings of participants and determine when form deviated from the starting position by more than a 10-degree change in the sagittal plane. The Angles App is designed to measure joint angles using video analysis (Figure 2).

The Angles App demonstrates appropriate reliability and validity in assessing knee joint range of motion, with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) exceeding 0.69 and strong validity, with correlation coefficients over 0.61. Additionally, the Angles App received an acceptable usability score with a System Usability Scale (SUS) rating above 68.17 The videos were imported into the Angles App to record the time where a 10-degree change occurred, which was compared to the visual estimation method.

Statistical Analysis

Data were initially entered and coded in Excel Spreadsheets, then transferred to IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 for analysis. Frequency tables and normalcy graphs were generated to examine correlations between SLB endurance and variables such as sex, age group, and activity level. The SLB hold times determined by the Angles App were averaged to provide normative data. Comparisons were also made between the time recorded from the Angles App where more than a 10-degree change occurred, and the time manually recorded by the researcher (visual estimation method) when they thought the participant made more than a 10-degree change in hip flexion angle from their starting position to determine accuracy of the clinician’s ability to determine accurate test form. Pearson product–moment correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the strength and direction of the association between SLB hold times measured using the Angles App and those estimated visually by the clinician. Correlation strength was interpreted using conventional thresholds, with values ≥0.50 considered strong.

RESULTS

The study examined asymptomatic subjects (77.7% female, 17.3% male; mean age 20.3 years) through convenience sampling. Among participants, 89.6% engaged in regular exercise, 16.5% had a history of musculoskeletal injuries, and only one participant reported previous back or lower-extremity injuries (greater than six months ago). The study team collected data on SLB performance, with normative values computed based on visual estimation and angle measurements. Three subjects were excluded during screening due to having sustained a lower extremity or back injury within the prior six months, leaving (77) participants in the study. Further analysis using box and whisker plots identified three outliers (one from dominant leg using visual estimation, and one each from nondominant leg using visual estimation and angle measurements).

After removal of outliers, the normative values were 65.2 seconds (SD = 32.7) for the dominant leg and 63.95 seconds (SD = 33.71) for the nondominant leg. In addition to the normative analyses, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationship between angle-based measurements and visual estimation. When outliers were excluded, strong and statistically significant correlations were observed for both limbs, with the dominant leg demonstrating a correlation of r = 0.815 (p < 0.001) and the nondominant leg demonstrating a correlation of r = 0.837 (p < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to establish normative values for the SLB endurance test and to evaluate the accuracy of visual assessment compared to a video-based angle detection app (Angles App). The findings provide preliminary normative data for SLB endurance and demonstrate that clinician visual assessment correlates strongly with app-based measurement, supporting the practical utility of using the SLB in clinical settings.

The mean hold times observed in this sample are 65.2 seconds on the dominant leg and 63.95 seconds on the nondominant leg, which offers an initial benchmark for healthy adults. These findings are consistent with existing literature suggesting the SLB is a valid and challenging test of posterior chain and core endurance.1,9 Compared to previously established norms for other core endurance tests (e.g., Sorensen, side plank), the SLB appears to demand a moderate level of endurance, aligning with its unique recruitment of gluteal muscles, hamstrings, and lumbar stabilizers.2,15

Normative values for the single leg bridge (SLB) in this asymptomatic cohort, 65.2 seconds (SD = 32.7) for the dominant leg and 63.95 seconds (SD = 33.71) for the nondominant leg, offer a unique measure of posterior chain endurance under single-limb stabilization. When compared to established core endurance norms, the current findings complement the broader pattern of core endurance capacities. For the anterior core, isometric plank endurance is typically categorized as “average” when held for 1–2 minutes, “above average” at 2–4 minutes, and “excellent” beyond 6 minutes.18 Mean plank times in healthy adults have been reported around 145 seconds (± 71.5),19 with Strand et al. noting median values of 110 seconds for males and 72 seconds for females.20 Lateral core endurance also varies, with studies reporting mean durations of 83.2 seconds (right side) and 81.5 seconds (left side) among male long-distance runners,21 while general adult populations often report shorter times, such as 34 seconds for males and 19 seconds for females.22 For trunk extensor endurance, the Biering-Sørensen test has demonstrated normative hold times ranging from approximately 100 to 200 seconds in healthy adults, with some samples averaging ~198 seconds for males and ~197 seconds for females.23,24

The SLB time assessed in this cohort is consistent with endurance outcomes reported for other core measures. Importantly, the SLB places greater demand on the gluteal and posterior chain musculature under unilateral stabilization, offering a distinct yet complementary perspective to anterior, lateral, and trunk extensor endurance assessments. Collectively, these findings support the use of a multi-test battery to capture the multidimensional nature of core endurance in clinical and research contexts.

The strong correlations found between clinician visual estimation and app-derived measurements (r = 0.815 for the dominant leg, r = 0.837 for the nondominant leg) reinforce the reliability of experienced clinicians in identifying SLB form breakdown. This is particularly relevant in clinical environments where access to motion analysis technology is limited. While the Angles App offers objective measurement with good reliability and usability,17 the current findings suggest that with appropriate training and standardized criteria, clinicians can achieve comparable accuracy using visual assessment alone. These findings are consistent with prior research indicating that trained clinicians can reliably identify joint deviations using visual estimation.16 While visual estimation offers a fast and accessible option for clinical environments, app-based tools such as the Angles App provide objective, quantifiable data with excellent intra-rater reliability (ICC > 0.69) and strong validity (r > 0.61) for joint angle assessment.17 The high agreement between visual and app-based methods in the current study suggests that clinicians can accurately identify form loss using standardized criteria, particularly when deviations exceed a 10-degree threshold. Thus, both methods offer valuable, complementary approaches for valid measurement of the SLB: visual estimation remains a valid and efficient option for clinical use, while app-based measurements may be preferable when greater precision is needed for documentation or research. Overall, these adjusted normative values and the strong correlation between the measurement methods provide a robust benchmark for evaluating SLB performance in healthy populations.

Notably, the current sample primarily consisted of healthy, physically active young adults, which may explain the relatively high endurance times observed. This aligns with prior studies suggesting that core endurance correlates more closely with physical performance and injury prevention than raw strength.3,4 The high percentage of participants reporting regular exercise (89.6%) may have positively influenced the normative values, and future research should explore SLB norms across more diverse populations, including sedentary individuals, older adults, and those with musculoskeletal conditions.

Importantly, the SLB’s value lies not only in its ability to measure endurance but also in its functional relevance. Previous research has linked SLB performance to athletic fitness and injury risk primarily through its ability to assess lumbopelvic stability, gluteal endurance, neuromuscular control, and movement patterns that mirror known biomechanical contributors to lower extremity injuries.6,7 Given its ease of administration, minimal equipment needs, and sensitivity to gluteal and hamstring deficits, the SLB may be a valuable screening tool in both athletic and rehabilitation settings.

While this study contributes to filling the gap in normative data for the SLB, it is not without limitations. The use of convenience sampling and a relatively homogenous sample limits generalizability. Additionally, although the Angles App provides reliable angle measurements, it requires a nominal cost ($0.99), and its use still entails some degree of subjectivity in determining the point of form loss when compared with more advanced motion capture software. Future studies may benefit from integrating electromyographic (EMG) data or 3D motion capture to further validate SLB kinematics and muscular engagement during the task.

CONCLUSION

This study establishes preliminary normative data for the SLB endurance test in healthy adults and supports the validity of clinician visual assessment for determining form loss during testing. The SLB provides a practical, low-cost, and functionally relevant measure of posterior chain and core endurance, complementing traditional core stability assessments such as the plank and Sorensen tests. Strong correlations between clinician visual estimation and app-based measurements confirm that trained clinicians can accurately identify performance breakdowns using standardized criteria, even without motion analysis technology. These findings reinforce the clinical applicability of the SLB as both an assessment and rehabilitation tool targeting gluteal and trunk endurance. Future research should validate these benchmarks across broader age ranges and clinical populations, integrating electromyographic or kinematic analyses to further refine test precision and establish predictive relationships between SLB endurance, injury risk, and functional performance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this manuscript. No financial or personal relationships exist between the authors, their institution, or any organization that could inappropriately influence this work.