Introduction

Yoga is an ancient discipline involving physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual training. It includes dynamic and static postures, breathing techniques, meditation, and relaxation methods that aim to improve body-mind awareness.1 Yoga has also been used as a form of treatment for chronic low back pain with moderate efficacy,2 although there has been little research on which poses are best suited for alleviating low back pain.

Yoga has become increasingly popular in the prior two decades. Among other common complementary health approaches, yoga was the most used and growing in popularity from 2002 to 2012.3 Yoga participation saw an increase in participation from the 18-44 age group in the United States between the years 2007 to 2012 (7.9% to 11.2%), and twice the increase it saw between 2002 and 2007.3 Approximately 24% of physical therapists in one survey (N = 153) reported regularly using yoga to strengthen major muscle groups at moderate or high intensity.4 Although physical therapists use yoga as a form of strength training, little is known about the activation of specific muscle groups during yoga poses, especially that of the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius.

Gluteal muscle strength is correlated with low back pain. Cooper et al.5 discovered a significant decrease in gluteus medius strength in subjects with low back pain compared to a control group. Kumar et al.6 concluded that gluteus maximus strengthening combined with core muscle strengthening and lumbar flexibility can be an effective intervention for low back pain. Similarly, Jeong et al.7 reported that strengthening the gluteal and abdominal muscles reduces low back pain, increases stabilization of the lower trunk, and improves balance more effectively than strengthening the abdominal muscles alone. Furthermore, people with gluteus medius weakness have more chronic low back pain as well as increased adduction and internal rotation in the hip joint during walking, potentially leading to knee injury.5,8,9 Gluteal strengthening aids in pain relief, improves gait patterns in patients after meniscus surgeries, and may also prevent lower extremity injuries in college athletes.10,11

In previous studies performing electromyographic (EMG) analysis of yoga poses, none have examined both gluteus medius and maximus activity across the five poses selected for this study (Tree, Warrior Two, Warrior Three, Half Moon, and Bird Dog). These poses were chosen because of their relative simplicity and low range of motion demands compared to other poses. They were also chosen because the position of the hip during these common poses was expected to elicit significant gluteal activation. The gluteus medius has been examined in each of these five poses at least once, but further study is warranted to confirm these findings.12–15 No study has examined gluteus maximus activation during Warrior Three Pose or Half Moon Pose, which were expected to elicit the highest gluteal activation. These two poses were anticipated to have the highest gluteus medius and gluteus maximus activation due to the required single-leg stance, hip external rotation, hip extension, and hip abduction positions for the stance and lifted legs. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to measure gluteus maximimus and gluteus medius activation via electromyography (EMG) during five common yoga poses. Identification of the poses that have the highest gluteal activation will help guide exercise selection and prescription.

The differences between male and female trunk and hip muscle activation during yoga poses has been investigated by one study that found females demonstrated higher activity compared to males.16 A secondary purpose of the current study was to examine differences between sexes and experience levels. It was hypothesized that experienced and female subjects would have higher average gluteal activation compared to inexperienced and male subjects, respectively.

Methods

Thirty-one healthy subjects (18 female, 13 male) between 18 and 35 years of age (mean age = 24.0 years; height = 1.7 m; weight = 74.7 kg) were recruited from a local university for this cross-sectional study. Subjects completed a survey to determine their classification of either inexperienced or experienced, which was defined as performing yoga directed by a certified yoga instructor one or more times in the prior year. Seven out of thirty-one (22.6%) were classified as experienced. Subjects completed an informed consent form and health questionnaire approved by the study institution’s Internal Review Board (IRB) for the protection of human subjects prior to testing. Potential subjects were excluded if they had any of the following: an upper or lower extremity injury requiring attention from a medical professional within the prior six months; an upper or lower extremity surgery within the prior year; current lower or upper extremity pain; history of any heart condition; or current pregnancy.

Prior to data collection, subjects were familiarized with the testing procedures, including a stationary bicycle warm-up, EMG electrode placement, MVIC testing, and the selected yoga poses. Subjects were asked to remove shoes and socks and perform the yoga poses on a standard yoga mat. Subjects underwent one familiarization trial for each of the five poses as shown in Figures 1-5. The descriptions in the table refer to the use of a right stance/forward leg, although both sides were tested.

As a warm-up, subjects pedaled a stationary bicycle for two minutes at a work rate of 60 Watts. Following the warm-up, the skin was shaved and abraded with alcohol wipes, and bi-polar wireless surface EMG electrodes (Noraxon, Scottsdale, AZ) were placed on the right gluteus maximus and right gluteus medius of each subject. No significant differences in muscle activity were noticed previously between sides in healthy individuals.15 One female researcher placed electrodes on all female subjects, and one male researcher placed electrodes on all male subjects. Electrode placement followed that of similar studies and standard practice.17,18 (Table 1)

Muscle MVIC testing was then performed on the right gluteus maximus followed by the right gluteus medius. A strap attached to an immobile object was used to standardize resistance during MVIC testing. Subjects were positioned prone with the knee flexed to 90 degrees and the strap resistance was placed at the distal femur to test the gluteus maximus. For the gluteus medius, subjects were in side lying with the hip to be tested nearest the ceiling, abducted to end-range, and slightly extended with the strap resistance placed immediately proximal to the lateral malleolus. (Table 2) Subjects completed two MVIC trials for each muscle. Subjects were asked to perform each MVIC for seven seconds, with 30 seconds of rest between each trial.17 All surface EMG data were collected at 4000 Hz using a Noraxon 880-16 Ultium Dash/ESP 16 Myomuscle and MyoMuscle 3.12 software (Noraxon, Scottsdale, AZ). Peak MVIC values for each subject and muscle were identified as the maximum value of a 50-millisecond moving average within the two corresponding MVIC trials and visually verified using custom written code (Matlab, The Mathworks, Natick, MA).

Each subject performed Tree Pose (Figure 1), Warrior Two Pose (Figure 2), Warrior Three Pose (Figure 3), Half Moon Pose (Figure 4), and Bird Dog Pose (Figure 5) on a standard mat as instructed by a certified yoga instructor using a standardized script. During Half Moon Pose, subjects were allowed to use a standard yoga block if needed (sturdy foam 9" by 6" by 4"). The order in which the poses were tested was randomized, and the subjects were blinded to the EMG activity levels. Subjects performed one trial of each pose bilaterally, holding the pose for seven seconds. For each pose and each side, five seconds of EMG data excluding the first and last second were analyzed. All pose EMG data were rectified and filtered using a 15 Hz high-pass and 500 Hz low pass fourth-order Butterworth digital filter. The filtered pose EMG data were then smoothed with a 150-millisecond mean absolute algorithm and normalized to the corresponding peak MVIC value. The maximum values from the smoothed and normalized EMG data (i.e., %MVIC) from each subject (31), muscle (2), pose (5), and leg (2) were identified and recorded (620 peaks total) for analysis. As a method previously used for interpretation, the following ranges were used for %MVIC data: low (0-20% MVIC); moderate (21-40% MVIC); high (41-60% MVIC); very high (higher than 60% MVIC).18

The mean and standard deviation of the maximum %MVICs were calculated and analyzed. Independent t-tests (α = 0.05) to examine differences between males and females and between subjects who had participated in yoga in the past year (experienced) and those who had not (inexperienced) were performed for each muscle tested in the five poses. SPSS v23.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) were used for data analysis.

Results

Data from thirty-one subjects were included. (Table 3) No significant difference was found in the measured mean %MVIC of gluteus maximus activity between male (33.3 ± 38.2) and female (27.8 ± 23.3) subjects (p = 0.133), or between experienced (26.8 ± 25.1) and inexperienced (30.9 ± 31.3) subjects (p = 0.328). However, a significant difference was found in the measured mean %MVIC of gluteus medius activity between male (11.6 ± 13.6) and female (9.3 ± 6.9) subjects (p = 0.026), and between experienced (7.8 ± 6.4) and inexperienced (10.6 ± 11.1) subjects (p = 0.050), indicating more gluteus medius activation among males than females, and more activation among inexperienced versus experienced subjects.

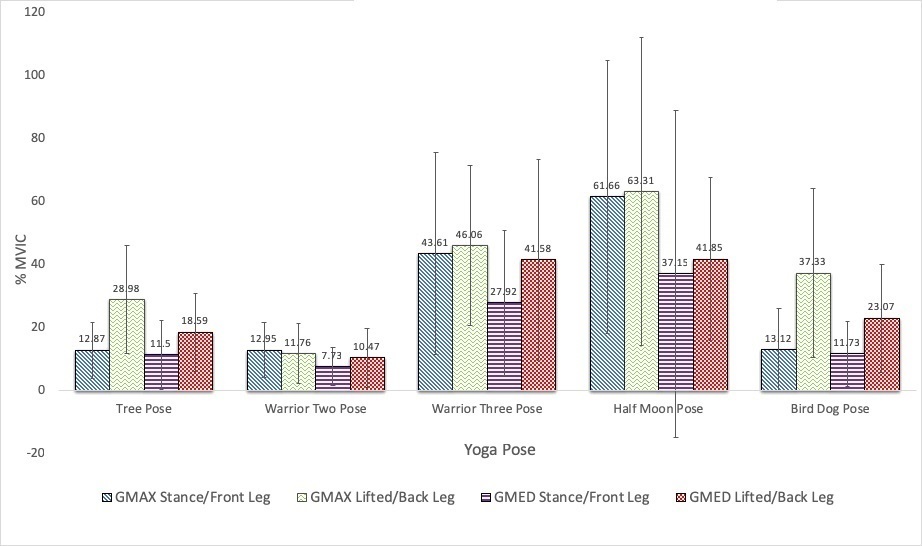

Greatest gluteus maximus activation occurred during Half Moon Pose on the lifted/back leg (63.3% MVIC), followed by Half Moon Pose on the stance/front leg (61.7% MVIC), then on the lifted/back leg during Warrior Three Pose (46.1% MVIC). The highest gluteus medius activation was recorded during Half Moon Pose on the lifted/back leg (41.8% MVIC), followed by Warrior Three Pose on the lifted/back leg (41.6% MVIC). Means and standard deviations of the EMG activity expressed as the %MVIC for each analyzed muscle in each of the five yoga poses are listed in Table 4, and presented in Figure 6.

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to determine the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius activation during five common yoga poses. The electrode placement and EMG analysis procedures of this study were similar to those used in previous studies.17,18 Exercises that generate moderate EMG activity (21-40% MVIC) have been proposed to produce a stimulus that will improve muscle endurance, whereas those generating high and very high EMG activity (41-60% MVIC and higher than 61% MVIC, respectively) have been proposed to produce an appropriate stimulus to induce strength gains.18 A key finding from this study is that the Half Moon and Warrior Three poses can serve as strengthening stimuli for both the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius muscles.

The secondary purpose of this study was to examine whether there was a significant difference between gluteus medius and gluteus maximus activation between male and female subjects and experienced and inexperienced subjects. There was not a significant difference in gluteus maximus activation between inexperienced and experienced or male and female subjects. But a significant difference in gluteus medius activation was found between male and female subjects and between experienced and inexperienced subjects. Males produced higher %MVIC of gluteus medius activity than females, and inexperienced subjects demonstrated higher gluteus medius activation than experienced subjects. Body weight distribution differences between sexes may account for the difference between males and females. The difference between experience levels may be explained by the possibility that experienced subjects might adopt a more relaxed and muscularly efficient posture with decreased muscle activation due to improved balance.

Tree Pose

Electromyographic activity for the gluteus medius during Tree Pose (Figure 1) was lower than expected. Wang et al.13 recorded mean gluteus medius EMG activity as 24.6% MVIC on the stance leg during a modified version of Tree Pose with older adults (mean age 70.7 years) who received 32 weeks of training. This was higher activation than the value found in the current study for the stance leg (11.5% MVIC) which may be due to the age and experience level differences between the subjects in the two studies. The lifted leg during the Tree Pose in the current study demonstrated 18.6% MVIC gluteus medius activation on average, for which there are no current literature comparisons. This level of activation does not reach the threshold for moderate activation that would make Tree Pose suitable for developing strength in the gluteus medius. These results were unexpected as Tree Pose seems likely to specifically activate the gluteus medius due to its leveling action on the pelvis that occurs during single-leg stance. One possible explanation for this unexpected finding is that subjects were not cued to maintain a level pelvis and consequently might have been resting on hip soft tissues in a position of contralateral hip drop instead of a level pelvis position that required stronger gluteus medius activation.

Gluteus maximus EMG activity was higher than gluteus medius activity for both the stance leg (12.9% MVIC) and lifted leg (28.9% MVIC). To the authors’ knowledge, no studies have determined gluteus maximus activation during Tree Pose.

Warrior Two Pose

In Warrior Two Pose (Figure 2), the front and back leg demonstrated low levels of gluteus medius activity (7.7% MVIC and 10.5% MVIC, respectively). These values are lower than those found by Wang et al.13 for the leading or front leg (16.4% MVIC); however, the trailing or back leg demonstrated similar activation (9.4% MVIC). Wang et al.13 used subjects with an average age of 70.7 years and included a certified yoga instructor performing the poses alongside the subjects, whereas the current study had the instructor reading standardized instructions to much younger subjects. This common pose is a double-limb stance pose, so it was not expected to produce large EMG activity for gluteus medius.

Gluteus maximus EMG activity during Warrior Two Pose was similar but higher than gluteus medius activity for both the front leg (13.0% MVIC) and back leg (11.8% MVIC). Beazley et al.18 examined gluteus maximus activity during Warrior Two Pose in untrained yoga subjects and also found low activation of the gluteus maximus at a level of 18.9% MVIC on the dominant side and 20.4% MVIC on the non-dominant side. The authors mentioned those with more yoga experience may have more activation of the gluteus maximus compared to relatively inexperienced subjects because those with experience learned to engage the muscles required for stabilization to a higher degree.18 The current study did not recruit based on yoga experience, and seven of the 31 subjects reported participating in yoga with a certified instructor the prior year. The relatively small number of experienced subjects recruited for the current study may account for the insignificant difference in gluteus maximus activity between experienced and inexperienced subjects.

Warrior Three Pose

It was expected that Warrior Three Pose (Figure 3) would produce high EMG activity in both the gluteus medius and the gluteus maximus given its use of single-leg stance, a lower extremity extended against gravity, and a horizontal trunk held against gravity by the stance leg. Gluteus medius EMG activity was higher in the lifted/back leg (41.6% MVIC) compared to the stance/front leg (27.9% MVIC). In a study by Kelley et al.,14 there was similar moderate gluteus medius activation (30% MVIC) for the stance leg during Warrior Three Pose. Those authors studied experienced practitioners who had at least five years of yoga experience and practiced a minimum of two times per week.

No literature was found about EMG activation of gluteus maximus during Warrior Three Pose. This pose has similar characteristics to the single-limb deadlift studied by Boren et al. who found gluteus maximus EMG activity to be 58.9% MVIC on the stance leg.19 That level of gluteus maximus activation for the Warrior Three Pose is higher than the activation level seen in the current study (43.6% MVIC of the stance/front leg and 46.1% of the lifted/back leg). The differences seen may relate to the difference between the yoga pose and the deadlift. Warrior Three Pose requires the upper extremities to be lifted next to the ears while the single-limb deadlift allows one hand to reach toward the floor, potentially increasing trunk and hip flexion, affecting hip extensor activation. Also, the single-limb deadlift allowed subjects to have the knees straight or bent, and the exercise was not statically held like the Warrior Three Pose. During the deadlift, subjects moved through a range of motion, and data collected for %MVIC were based on the highest peak value of three repetitions during the middle 3/5ths of the time to perform the exercise, which could explain the 15% difference in gluteus maximus activation.19

Half Moon Pose

Half Moon Pose (Figure 4) was expected to also have high EMG activation of the both the gluteus medius and the gluteus maximus. Activity of the gluteus medius during the Half Moon Pose was higher than all poses in the current study on the lifted/back leg (41.9% MVIC). The stance/front leg showed 37.2% MVIC for the gluteus medius. This was higher than the 25-30% MVIC for the gluteus medius found by Kelley et al.14 for the stance leg during the Half Moon Pose. The moderate demand for gluteus medius activity is likely due to the hip abduction, single-leg stance, and balance requirements during this pose.

There was no prior research found for gluteus maximus activation during Half Moon Pose. As expected, this pose had one of the highest gluteus maximus activation values for the stance/front leg (61.7% MVIC) as well as the lifted/back leg (63.3% MVIC). The very high activation of gluteus maximus during Half Moon Pose may be due to the bilateral hip external rotation requirement while holding the raised leg and trunk against gravity. The very high gluteus maximus activation during this pose on both legs may be beneficial as a strengthening stimulus.18

Bird Dog Pose

Bird Dog Pose (Figure 5), sometimes referred to as a quadruped arm and leg lift, elicited low to moderate activity of the gluteus medius (11.7% MVIC and 23.1% MVIC for the stance/front and lifted back legs, respectively). Ekstrom et al.15 did not study activity in the stance/front leg, but they found almost twice as much gluteus medius activity (42% MVIC) on the lifted/back leg. This difference in activation of the gluteus medius may be due to the number of practice trials allowed. Subjects in the current study performed one familiarization trial, while subjects were allowed an unspecified number of familiarization trials in the study by Ekstrom et al.15 Small and unreported differences in electrode placement may also contribute to the difference between studies.

The current study found moderate activation of the lifted/back leg (37.3% MVIC) and low activation of the stance/front leg (13.1% MVIC) for the gluteus maximus during the Bird Dog Pose, suggesting it could be an appropriate stimulus for endurance training but not strength training. Ekstrom et al.15 found 56% MVIC for the gluteus maximus of the lifted/back leg. This difference in activation levels could be due to the aforementioned study differences as well as foot positioning. In the current study, subjects were instructed to point the toes towards the floor, potentially increasing anterior leg muscle activity and subsequently decreasing posterior leg muscle activity. Although not specified by Ekstrom et al.,15 the figure used to demonstrate the exercise demonstrates the use of ankle plantarflexion during the Bird Dog Pose, potentially increasing activity of posterior lower extremity muscles including the gluteus maximus.

Limitations and Future Research

In the current study, the order of yoga poses was randomized, and both the researchers and subjects were blinded when possible, yet limitations remain. It is possible that subjects did not generate a true MVIC of each muscle tested due to lack of effort or suboptimal positioning. Attempts were made to minimize these potential limitations by standardizing instructions to subjects, standardizing pose positioning methods, and using MVIC testing methods consistent with previous studies.

The most effective method for instructing yoga poses has not yet been examined. The use of standardized instruction to subjects instead of individualized instruction may have limited gluteal activation in the current study. Gluteal muscle activity during yoga poses was not studied in subjects with pathology, so generalizing results to an injured population should be avoided. Future research should examine the effects of strength training using the Half Moon Pose and Warrior Three Pose. Examination of their effects on pathology and performance is also warranted.

Conclusion

The results of the current study indicate that the Half Moon Pose and Warrior Three Pose had the highest activation for the gluteal muscles studied in healthy young adults with variable yoga experience. The high to very high activation levels found indicates that both of these poses have the potential to provide strengthening stimuli. Higher gluteus medius activation was demonstrated by males compared to females, and by inexperienced subjects compared to experienced subjects. The information from this study can help coaches, athletes, yoga instructors, and clinicians determine which yoga poses to consider for gluteal strengthening or endurance exercises.

Conflict of Interest

There are no potential conflicts of interests, including financial arrangements, organizational affiliations, or other relationships that may constitute a conflict of interest regarding the submitted work.