INTRODUCTION

An important issue in elite football settings is quantifying muscle function for performance. Identifying muscular dysfunction/weakness through appropriate testing related to injury aetiology provides practitioners with valuable information to intervene with appropriate programs to address these issues. Such programs may mitigate the negative impact injuries can have on team performance through time loss and financial cost.1 The physical demands of football (soccer) are known to have increased2 and risk of injury is high.3,4 Consequently, performance practitioners in elite settings aim to implement testing protocols to identify an athlete’s readiness to train/play, maximising performance and minimising potential injury risk factors. Muscle strength has been a key etiological factor associated with injury risk.5,6 Muscle injuries are a predominant feature in many football-related investigations.7 The use of isometric testing to identify reductions in muscle strength is common practice,8 and integral for the decision-making process that takes place on a daily basis in an elite football setting to maximize performance and increase player availability.

Literature has focussed heavily on quantifying hamstring and quadricep muscle function and the reliability of such measures are well reported.5,6 This has led to widespread use of these measures in practical settings, particularly in elite football, where muscle testing equipment is widely available. This focus has been predominantly driven by injury occurrence, identifying risk in athletes, and increasing performance. Occurrence of posterior lower leg injuries is prevalent in elite football and team sports.4,9 It is important to note the key contribution of the posterior lower leg, particularly the soleus, on running performance,10–12 highlighting the need within elite sport to identify reliable methods to quantify soleus function. Reliable quantification methods are essential for effective monitoring or athlete profiling and could provide practitioners with data that can influence decision making in relation to readiness to train/play, training prescription and rehabilitation processes.13

Isometric muscle strength testing is commonly utilized to determine musculoskeletal status, markers for return to play and address strength deficits affecting performance.14 The use of isometric muscle strength testing is commonly utilized within elite sport, due to it being less provocative than eccentric testing.15,16 This allows testing to be completed more frequently and during heavy fixture congested periods, identifying any deficits that may be associated with reductions in performance or potential injury risk factors. Isometric contractions are a highly reliable and efficient way of measuring and monitoring changes in the generation of force.17 The isometric soleus strength test (ISST) is utilized to determine the strength of plantar flexors, notably the soleus muscle. No standardization of testing or reliability data is available to the authors knowledge for the ISST. A standardized and reliable measure that can be utilized to test for isometric soleus strength may provide medical and performance practitioners with the utility to optimally monitor and profile athletes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the test-retest reliability of the isometric strength test of the soleus and propose a standardized protocol for its use within an elite male football population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

An a priori power calculation using G-power indicated that a total of 30 participants would be required to detect a high correlation with an alpha of 5% and power of 80%. Thirty male elite academy footballers (age = 22.76±5.0 years, height = 180.0±0.8 cm, weight = 70.57±4.0 kg) participated in this study during the 2019-2020 season. Participants were advised of the advantages and risks of the study and the testing protocol was clearly defined verbally before participants provided written and verbal consent to participate, with the option to withdraw from testing at any point. Participants had a minimum of four years’ experience in resistance training and strength-based testing protocols and met the inclusion criteria of healthy with no current injury and were of male gender. All players eligible for the study were in full training, free from injury, and available for competitive selection. The host football club permitted the dissemination of anonymous data for publication of the study findings and the study commenced in accordance with the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Central Lancashire ethical committee (STEMH).

This study evaluated the test-retest reliability of the ISST within an elite male academy football population using a correlation design. Data collection was performed in a temperature-controlled physiology laboratory on site at the host football club training ground by the same two researchers throughout. Testing occurred at the same time of day for the re-test data 72hrs apart to account for potential diurnal or circadian rhythm that could have affected performance.18 Players refrained from strenuous exercise between these two testing periods and completed their normal daily routine.

Study Design

Participants were familiar with the test protocol, as it has been utilized within the previous season consistently throughout the clubs’ regular screening, testing and readiness to train/play protocols. Testing for the present study took place within pre-season. Test procedures for the ISST were appropriately standardized following previous recommendations in the literature.19 Before the commencement of ISST bar height was determined for each individual participant, based on seating position and maintenance of hip, knee and ankle joints at 90-degrees, in order to achieve the correct body position for each test.19 Seating position, rack bar, crocodile pin and bar position were recorded for protocol standardization ahead of scheduled testing. Procedures were identical between both testing sessions. Although there is no standardized warm up for the ISST, it is apparent from other isometric tests that a derivative of the movement performed should be incorporated.15,16,19,20 Participants therefore completed a standardized warm-up beginning with a 10-minute of supervised stationary cycling 1.5 W kg −1, cadence of 60 rpm on a cycle ergometer (Wattbike Ltd, Nottingham, UK), followed by five minutes of dynamic stretching, before advancing to two warm-up sets of IMTP soleus lifts at 50% and 75%.

The BTS-6000 force decks platform (VALD Performance, Newstead, Queensland Australia) were calibrated by the manufacturer to evenly distribute bodyweight across the two platforms. The participant was seated in a position of 90-degrees hip and knee flexion, feet hip-width apart and of equal distance from the center of the platform. While the use of a “self-selected” body position is likely to be advantageous for testing performance, it is not recommended without ensuring that the hip, knee, and ankle joint angles are at 90 degrees, due to the potential influence of varied body positions on force generation.19,21 An Airex (Airex AG Sins, Switzerland) cushion was placed on top of the participants’ thighs, with the bar placed on top. The individual was then asked to position the metal bar in line with their pre-recorded position, within the crocodile pins on the Sorinex XL racking system (Sorinex, Lexington, SC, USA), with the bar placed directly over the lateral malleolus. Participants were encouraged to maintain a vertical posture throughout the movement, with hands away from the bar due to interference previously recognized. Before each test, this position was ascertained, with the knee joint angle verified using a goniometer. The width of the participants’ foot position was measured using a standard measuring tape to ensure consistency between tests. After performing two warm-up efforts for the ISST at 50 and 75%, the participant performed three maximum efforts (three second hold with a one-minute rest between reps). Participants were advised to maintain a neutral foot position and minimal pre-tension on the bar until verbal instruction was given. Before each rep the athlete was guided by a countdown (“3, 2, 1”) and instructed to push for three seconds up and against the bar as hard and as fast as possible.18

DATA ANALYSIS

Initial data analysis was performed using Forcedecks software (VALD Performance, Newstead, Queensland Australia) and transferred to a spreadsheet program (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Data was recorded for each of the three maximum efforts of three seconds over the two sessions utilized to ascertain reliability of the test. An average was taken for each participant and relative reliability was calculated to identify the relationship for each limb. A Pearson’s correlation measured the relationship between the two testing sessions. The following criteria quantified magnitude of the correlation <0.1, trivial; >0.1 to 0.3, small; >0.3 to 0.5, moderate; >0.5 to 0.7, large; >0.7 to 0.9, very large; and >0 to 1.0, almost perfect, with statistical significance set at p ≤ 0.05. Reliability in units of measurement was calculated for the interpretation of group mean scores and the individual scores of Peak Force (PF) (N) including Standard error of measurement (SEM) and minimal detectable change (MDC). The formulas used for both SEM and MDC followed previous calculations described by Ransom et al.14 To analyze for levels of agreement a Bland-Altman method was completed.22 Prior to completing statistical analyses the distribution of data was assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk Test and found to be suitable for parametric statistical testing. All statistical analysis was completed utilising SPSS software version 26.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA)

RESULTS

A significant correlation was demonstrated between tests (p<0.001). A very large correlation demonstrated for the ISST (Right: r = 0.89; Left: r = 0.79) (Table 1). Figure 1 highlights the linear relationship in the reliability data, bilaterally.

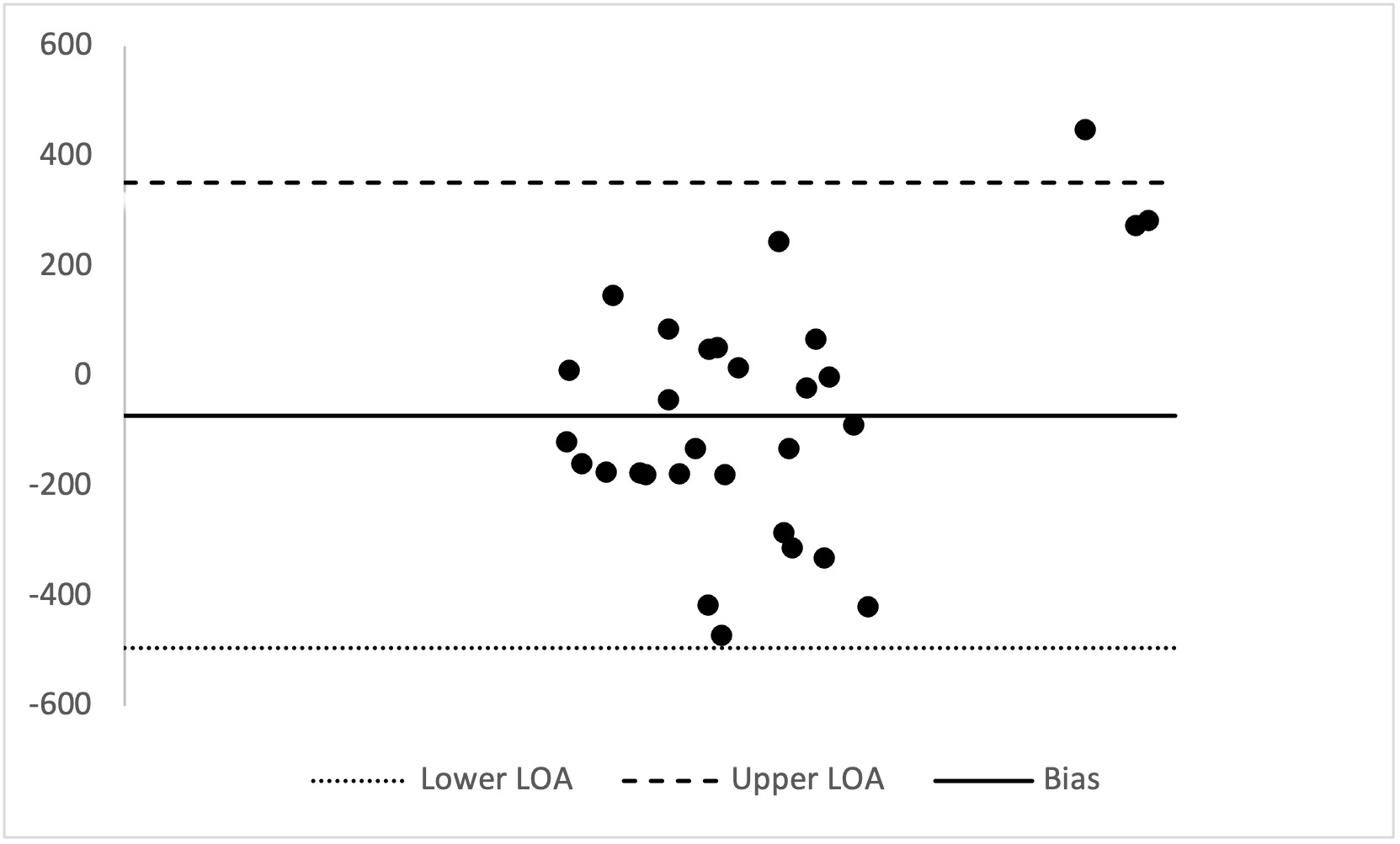

Figure 2 and 3 display the mean differences between the test-retest data for the ISST with the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals displayed for the measures taken.

Bilateral levels of agreement were found to be +/- 2 standard deviations (SD) of the interval of agreement bilaterally for ISST (Levels of agreement (LOA): Right: Upper 352.49 - Lower -494.76; Left: Upper 523.82 - Lower -591.30. No significant difference between the mean scores for the right (p=0.09, CI: -153.21-10.95) or left (p=0.52, CI: -139.81-72.33) test-retest mean scores were found, indicating that high levels of agreement were identified between the two tests bilaterally.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the reliability of the ISST in an elite academy football population. It was hypothesised that reliability would be high for the ISST in this population. The primary findings from this study demonstrated high reliability in male academy footballers for the ISST. High levels of agreement were demonstrated between the two ISST tests bilaterally with 95% of differences demonstrated to be less than two standard deviations away from the mean.22 Indicating that the ISST can be utilized in an elite sporting environment to reliably quantify isometric strength of the soleus. The SEM (%) and MDC values indicated absolute reliability across measures suggesting changes in strength in an individual athlete can be determined from this test (Table 1).

Isometric strength testing is commonly used for identifying modifiable injury risk factors or assessing outcomes of performance enhancement programs. Confidence within the test in terms of repeatability is important for sports medicine and performance practitioners to consider. The ability to evaluate an athlete’s lower limb capacity to generate force is an integral part of strength profiling and evaluating the efficacy of training interventions.23 The strength of plantar flexors, notably the soleus muscle may be determined through the ISST. The test position in 80-90° knee flexion has been shown to inhibit the force generated by gastrocnemius, therefore primarily evaluating the strength of the soleus.19 Currently no standardised testing protocol exists for ISST. Recently Ransom et al.14 indicated the importance of repeatability in terms of detecting true changes in response to injury or load over time in order to enhance athlete profiling. Consequently, it is important to report both test-retest and absolute reliability. This provided assessment of variability between repeated measures as well level of agreement in PF data.14 Current results provide confidence in the measure of isometric soleus muscle strength through the ISST by highlighting normal variance and levels of agreement between testing sessions.22 Evidently, isometric soleus PF measures in the current study were reproducible both between sessions. Results from the current study on isometric soleus strength testing, support similar findings by De Witt24 and Haff et al.25 The current study offers further evidence that ISST PF is a useful metric for reliably quantifying maximum strength from isometric strength test protocols.

Medical and performance practitioners working within an elite performance setting may consider using the ISST to evaluate athletes’ optimum and PF capabilities due to the high reliability of the test identified in the current study. Practitioners may be reluctant to conduct maximal eccentric strength testing due to the potential risk of injury. Thus, prompting the need to consider the implementation of the ISST as an alternative measure to determine maximum strength and/or PF. The ISST being isometric in nature, decreases the risk of fatigue and subsequent risk of injury, thus providing a measure that can be utilized in fixture congested periods.24 Earlier researchers have advocated for in-depth analysis of players which should include isometric muscle strength (albeit in the hamstrings as an example)26 which may influence optimal training prescription.27 From an applied perspective ISST quantifies vertical forces which are essential mechanical components for specific athletic functions such as acceleration, sprinting, distance jumping and directional changes.28 Reliable screening techniques such as the ISST may support the identification of at-risk or strength deficient players and consequently the adaptation of preventative interventions or programs targeting individuals can be derived from such information. This initial study only considered PF as a metric, due to its strong association to functional activities and movement patterns.19 Any future work in the area should consider other metrics, such as rate of force development (RFD).

SEM (%) and MDC data provided measurement error for absolute reliability (Table 1). Analysis of PF data before and after interventions may be assisted by the MDC data from the current study findings. For the ISST, SEM demonstrated 161.41-216.24N and a small relative index of 9.09 – 12.47%, with any individual PF changes above 25.19-34.56N being expected to be a ‘real’ change. Further investigation in other populations and ages within elite or normative populations may be beneficial to determine agreement. Although this type of data may provide sports medicine and performance practitioners with guidance on ‘real’ changes in strength that may occur, as presented in recent similar studies.14

Due to the high reliability demonstrated within the present study the ISST for soleus this metric may be a useful objective marker for quantifying posterior lower limb function. Furthermore, the equipment allows for assessment between dominant and non-dominant legs through metrics derived from the Forceplate software (VALD Performance, Newstead, Queensland Australia). Future studies may consider further investigation of dominant or non-dominant limb through utilization of the ISST. For example, recovery of lower limb muscle strength in the dominant leg is reported to be compromised for up to 72 hours after competitive fixture.6,29 While a specific definition of muscle imbalance has yet to be agreed upon, debate continues as to the contribution of imbalance as a risk factor for professional football injury,30 to which the use of a measure such as the ISST may be a valuable addition.

Limitations require highlighting, despite the results of this study demonstrating high absolute and relative test-retest reliability. The sample utilized in the study was a convenience sample from a specific male, academy age elite football population. Data therefore may not be extrapolated to other genders, age groups, sports or non-sporting populations. Further investigation is required to determine whether equivalent findings exist. Because bilateral limb testing was utilized in accordance with Ransom et al.14 the authors acknowledge that bilateral limb deficit phenomenon may exist, but measures to minimize the likelihood were highlighted in the methodological approach.31

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that the ISST is a reliable method for assessing maximal isometric PF in the soleus musculature of male elite academy footballers. These results suggest that the ISST may be beneficial for performance practitioners for profiling soleus function of athletes.

.png)

.png)