INTRODUCTION

The use of flywheel devices in resistance training can be dated back over one hundred years, with an increased interest since 1994 due to the development of flywheel devices to counteract muscle strength loss and atrophy for astronauts undertaking space flight.1 Inertial flywheel resistance training (IFRT) has been found to be a beneficial alternative or compliment to traditional resistance training methods in both healthy athletic populations and in rehabilitation for some musculoskeletal injuries.2 The beneficial effects of flywheel training in athletes for increasing muscle strength and hypertrophy have been well documented, but only recently has evidence emerged regarding its beneficial applications in the rehabilitation setting.3 IFRT incorporates the use of inertial resistance via a rotating flywheel device that requires increased muscle contraction speeds compared to standard resistance training, which with repeated training over time can lead to increases in muscular power and strength.4–6 During maximum effort concentric movements, rotation of the flywheel generates kinetic energy, which when braked during the return eccentric movement causes increased eccentric resistance to working muscles and tissues.7 Due to the isoinertial type of resistance involved, greater eccentric muscle activation can occur compared to traditional resistance training using free weights.8 A plethora of beneficial effects have been demonstrated on muscle tissue with flywheel training, including increased muscle power, strength, length, muscle activation, hypertrophy, and an increase in fast twitch muscle fibers.9 Improvements in athletic performance indicators such as change of direction ability, post activation potentiation, maximal running speed and vertical jump height has also been demonstrated in athletes.10–13 Despite eccentric overload of muscles occurring during flywheel training, muscle adaptations have been found to occur without increased pain or risk for musculoskeletal injury during training.14 Eccentric biased training such as flywheel training activates the stretch-shortening cycle more efficiently than traditional isotonic resistance training, which can increase muscle adaptation through the addition of sarcomeres known as sarcomerogenesis, which may lead to greater adaptations if applied during injury rehabilitation.15 The use of IFRT has been found to not only improve athletic performance but it may also decrease the risk of musculoskeletal injury during competition in athletes.16,17 Due to its beneficial effects on muscle tissue, IFRT can also be used in isolation or in combination with traditional rehabilitation methods, which may lead to enhanced outcomes, particularly for acute muscle injuries and degenerative muscle conditions such as sarcopenia.18,19 Muscle weakness and atrophy can also be reduced during post-surgical early rehabilitation for joint injuries, such as after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, when muscle atrophy is a common problem.20 Studies have shown that IFRT can be used in all stages of musculoskeletal injury rehabilitation to increase muscle strength and functional performance, from post-surgical to return to sport phases.21–23

Tendinopathy represents a spectrum of tendon pathology, associated with changes to the structural tendon collagen matrix, presence of various inflammatory cells and clinical symptoms of pain and impaired performance, with potential for progression to a chronic degenerative condition.24 Tendinopathy is common in athletes with high training demands and is associated with repetitive tendon microtrauma, with Achilles and patellar tendinopathy having the highest prevalence in athletes.25 Traditional eccentric training has been the gold standard first-line management approach for tendinopathies for the last two decades, due to its documented beneficial clinical effects for both upper and lower limb tendinopathies.26,27 Despite the largest body of evidence existing for eccentric training, heavy slow resistance training (HSRT) involving both concentric and eccentric actions has been shown to have comparable positive clinical outcomes.28,29 Due to these findings, some experts have suggested there is no scientific rationale for eliminating concentric actions in tendinopathy rehabilitation, with IFRT a potentially efficacious rehabilitation method due to having both a concentric and eccentric overload component and therefore requiring less overall training exposure, which may improve adherence.30–32 Despite this, there are a lack of recommendations for the use of IFRT and it is not routinely used in clinical rehabilitation for tendinopathies. The effects of flywheel training on healthy and pathological tendons are not well documented, with some evidence indicating improvements in tendon stiffness.33 Due to a paucity of research, it is unclear what effects IFRT may have on tendons, but the induced muscular adaptations also suggest mechanical tendon properties, collagen metabolism and tendon remodelling may be enhanced due to the eccentric overload effect.34,35 The application of progressive tendon loads during rehabilitation is essential to not compromise tendon healing, with the precise dosing parameters of resistance training loading a critical consideration.36 Prolonged time under tension with traditional heavy loads and increased training frequency during the early phase of tendon rehabilitation could be counterproductive and compromise tendon healing.37 Despite the potential applicability and possible beneficial physiological mechanisms of IFRT on tendon healing, the method of training has received a dearth of attention in tendon rehabilitation, despite the clinical benefits found for other musculoskeletal conditions and the knowledge of resistance training being the most evidence-based treatment available for tendinopathies.38,39 Therefore, the objective of this scoping review is to evaluate current research on the use of IFRT for treating tendinopathies. The scoping review will be guided by addressing the following review questions on specific aspects of IFRT interventions within tendinopathy rehabilitation: 1. What outcomes have been reported for IFRT in rehabilitation for tendinopathy and which outcome measures have been used? 2. What IFRT intervention and device parameters have been used in published studies? 3. What physiological mechanisms explaining effects of IFRT for tendinopathy have been investigated in published studies?

METHODS

Due to the exploratory nature of the research questions of this review, a scoping review was conducted as they are recommended for mapping key concepts, evidence gaps and types of evidence within a particular field and can help guide future research and the possibility of conducting systematic reviews on the topic.40 The scoping review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analysis extension for Scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR).40

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for the scoping review were guided by a modified PICO (PCoCo), which is recommended for scoping reviews.40 The review considered studies with adult participants aged eighteen years or older with a diagnosis of any tendinopathy for any time duration. All lower and upper limb tendinopathies were considered for inclusion, such as gluteal, hamstring, patellar, Achilles, rotator cuff and lateral elbow. Any tendon condition characterized by common tendinopathy symptoms, in the absence of a full thickness tendon rupture were considered for inclusion. A clinician’s diagnosis based on verifiable clinical features including pain location, response to palpation or tendon loading with specific tendinopathy tests were accepted for inclusion. Studies including participants with other concurrent injuries or medical conditions were excluded. The concept of interest was IFRT for the treatment of any tendinopathy, including any type or format. Therefore, any muscle contraction type performed with IFRT, including eccentric, concentric, isotonic, isometric, plyometric, general strength training, or combinations of these exercise types were considered. The IFRT intervention could be used as a first or second-line intervention and may be delivered in isolation or combined with other treatments. The context considered for inclusion included any setting in which IFRT was delivered by health or exercise professionals, in a supervised or unsupervised manner, using any methods for training progression and compliance. This scoping review considered both experimental and quasi-experimental study designs for inclusion, including randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case series and case reports. Unpublished studies, systematic or narrative reviews or reports were not considered for inclusion.

Search strategy

The search was carried out using a uniform search strategy across all databases (Appendix 1) and it included key words from two main concepts: IFRT (‘flywheel’, ‘inertial’, ‘isoinertial’, ‘eccentric overload’), and Tendon (‘tendon’, ‘tendinopathy’, ‘tendon injury’). The Boolean operators “Or” and “And” were used to link the key words from each concept and to link the concepts themselves, respectively. A 3-step search strategy was implemented in this scoping review. It incorporated the following: 1) a limited search of MEDLINE and CINAHL using initial keywords as, followed by analysis of the text words in the title/abstract and those used to describe articles to develop a full search strategy; 2) The full search strategy was adapted to each database and applied to MEDLINE, CINAHL, AMED, EMBase, SPORTDiscus, and the Cochrane library (Controlled trials, Systematic reviews). The following trial registries were also searched: ClinicalTrials.gov, ISRCTN, The Research Registry, EU-CTR (European Union Clinical Trials Registry), ANZCTR (Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry). Databases were searched from inception to January 18th, 2022 (Search performed on January 18th, 2022). The search for relevant grey literature included Open Grey, MedNar, Cochrane central register of controlled trials (CENTRAL), EThOS, CORE, and Google Scholar. 3) For each article located in steps 1 and 2, a search of cited and citing articles using Scopus and hand-searching where necessary, was conducted. Studies published in a language other than English were only considered if a translation was available as translation services are not available to the authors.

Study selection

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into RefWorks and duplicates removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers and assessed against the review inclusion criteria. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full, with their details imported into Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). Two independent reviewers assessed the full text of selected articles in detail against the review inclusion criteria. Any disagreements that arose at any stage of the study selection process were resolved through discussion or by input from a third reviewer. The results of the search are reported in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR. In accordance with guidance on conducting scoping reviews, critical appraisal was not conducted.40

Data extraction

Data were extracted from sources included in the scoping review by one reviewer, with independent data extraction by a second reviewer for at least 10% of studies. The data extracted included specific details regarding the population, study methods and key findings relevant to the review questions. The data extracted included dimensions such as study type, purpose, population & sample size, methods, details of the IFRT intervention, specific exercises, outcome measures used and clinical outcomes. Details of the IFRT interventions included type, dosage, device and intervention parameters, and methods used to progress the training stimulus. Data were also extracted on any physiological mechanisms such as effects on tendon morphological and mechanical properties, which have been investigated to explain the effects of IFRT in tendinopathy. The extracted data are presented in Table 1 with an accompanying narrative synthesis.

RESULTS

Included study characteristics

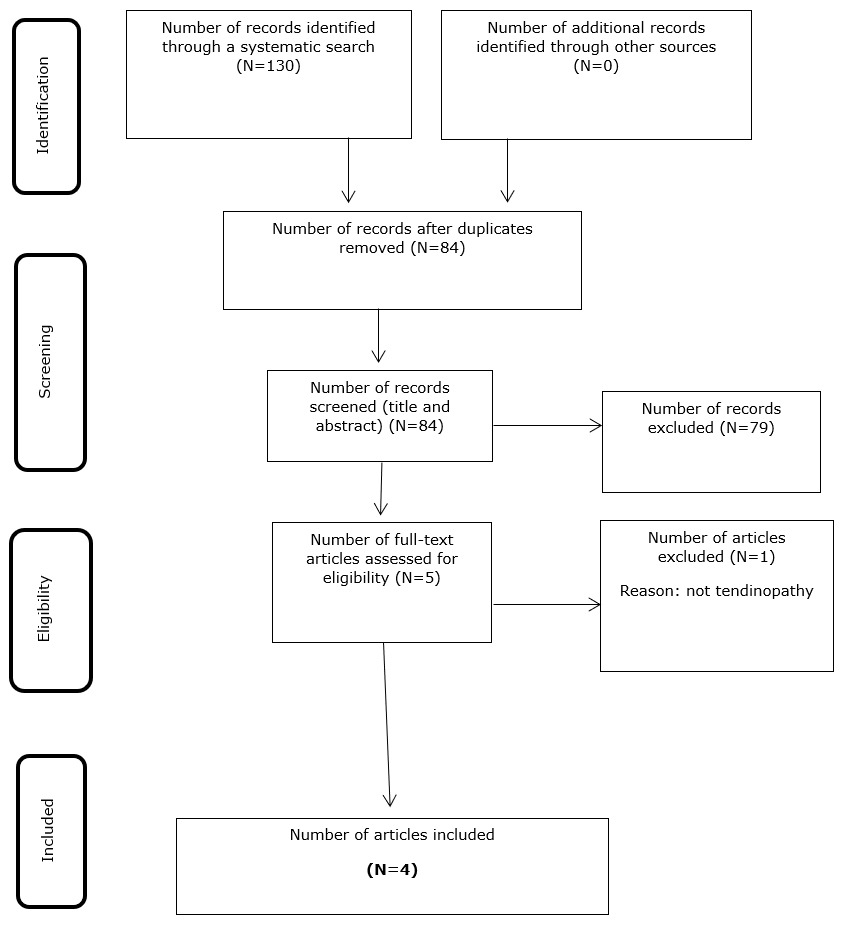

The literature search yielded 130 articles, reduced to 84 after removing duplicates, of which four met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review, with the search results summarised in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1). An overview of the characteristics, IFRT parameters and outcomes of the included studies are provided in Table 1. The four studies investigated the effects of IFRT on patellar tendinopathy, including one randomized controlled trial (RCT),41 one case series,42 and two cohort studies.43,44 No studies investigating the effects of IFRT on other tendinopathies were found in the literature search. The sample sizes of included studies ranged from 10-42, with a total of 125 participants with patellar tendinopathy. All included studies investigated the effects of a IFRT intervention, one in isolation,42 one compared with HSRT,41 and two combined with intratissue percutaneous electrolysis (EPI).43,44 The duration of IFRT interventions ranged from 6-12 weeks. The most common exercises used for the IFRT interventions were, leg press in four studies, squats in one study, and knee extension in one study.

Outcome measures

All four studies assessed patient reported pain and function as an outcome measure with IFRT using the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment Patellar (VISA-P) for patellar tendinopathy. One study used the VAS scale for pain, two studies used the Tegner scale, two studies used the Roles and Maudsley scale, one study used the Blazina scale, and one study used the Patient Specific Functional Scale (PSFS). One study also assessed quality of life using the EuroQol-5D. Two studies assessed the effects of IFRT on strength and power, using methods such as maximal strength testing and the counter movement jump test. One study used ultrasound to assess patellar tendon thickness and doppler signal to measure tendon neovascularization. One study also used surface electromyography (EMG) to assess muscle function.

Outcomes

The four studies included in this review that assessed the effects of IFRT on clinical outcomes in patellar tendinopathy all found significant improvement in pain and function as measured by the VISA-P. However, only two studies used IFRT in isolation,41,42 whereas the other studies implemented IFRT combined with EPI, which may have affected outcomes.43,44 The two studies that assessed strength outcomes, all found increases in strength and power following the IFRT intervention. The only RCT in patients with patellar tendinopathy,41 found equal improvement compared to HSRT, in terms of pain, function, strength, power, patellar tendon thickness and neovascularization.

Training parameters

The four included studies all used specific IFRT devices in their interventions, with three using leg press machines from the same manufacturer (YoYo Technology AB, Stockholm, Sweden). Whereas these studies focused on one specific exercise and device, the other study41 included three specific devices (Ivolution, Sunchales, Argentina) to allow three different exercises in the intervention; leg press, knee extension and squat. Despite some variances in the sets and repetitions of prescribed exercises, exercise prescription was largely homogenous across the included studies. Two studies prescribed 4 sets of 10 repetitions, once per week, with the first two repetitions used for increasing the inertial resistance, and repetitions 3–10 were always executed with maximal effort.41,42 The studies following this same protocol allowed for two minutes of rest between sets. The other two studies prescribed 3 sets of 10 repetitions, twice per week, all repetitions were performed with maximum intensity for 10 repetition maximum (RM).43,44

DISCUSSION

The main findings from this scoping review are that despite the paucity of research on IFRT as a treatment for tendinopathy, the available albeit preliminary evidence indicates that IFRT is a potentially clinically effective management option for patellar tendinopathy, particularly in athletic populations. All studies found in the literature were conducted on patellar tendinopathy, with two studies findings pain and function improvement with IFRT in isolation, and two studies finding clinical improvement with IFRT combined with EPI. Two studies also found significant strength and power improvement with IFRT, with one study finding positive tendon adaptations on ultrasound. The findings from the RCT included in this review may be of particular significance to the clinical rehabilitation and prevention of patellar tendinopathy, particularly in athletes.41

For several decades, heavy eccentric and more recently, heavy slow resistance training have been considered the conservative cornerstone of manging lower limb tendinopathies, as supported by evidence.45 However, the preeminent HSRT protocol in patellar tendinopathy, known as the Kongsgaard protocol in reference to the authors who developed it, which has shown efficacy in several RCTs,29,46–50 was found to be no more effective than IFRT, for improving pain, function, strength, power, and tendon properties. The RCT highlighted how several clinical and physical outcomes could be improved by IFRT at a comparable level to the gold standard HSRT protocol.41 Somewhat surprisingly, this RCT was the only study included in this review that assessed tendon properties as an outcome measure, finding improvements in tendon thickness and neovascularization as assessed by ultrasound and doppler signal. Despite this, previous studies examining the effects of IFRT on healthy tendons, have shown potential beneficial changes in tendon structure, suggesting the same is true for pathological tendons.33 Although further confirmatory research is required to confirm that IFRT induces positive adaptations in tendinopathy, the preliminary findings from this RCT are encouraging. Further studies with larger sample sizes are required to confirm the efficacy of IFRT as a patellar tendinopathy treatment, with the evidence from studies included in this review suggesting possible clinical benefits. There is also a clear scientific rationale for IFRT having potential clinical benefits in tendinopathy, due to the previously highlighted physiological mechanisms it induces, particularly the muscular and tendon responses induced by eccentric overload training.4,9

Although the focus of this review was on the use of IFRT in the rehabilitation of tendinopathy, findings from other studies have suggested a possible role for IFRT in prevention or in-season management of patellar tendinopathy. In a sample of 81 jumping athletes who were at high risk for developing patellar tendinopathy due to repetitive tendon loading, a once weekly IFRT protocol added to normal in-season sports training led to strength and power improvements, along with no increases in patellar tendon pain or diagnoses of patellar tendinopathy within the sample.51 Given the high prevalence and incidence of patellar tendinopathy in elite jumping athletes,52,53 this evidence of a prophylactic effect of IFRT is a potentially significant finding. Although more studies are required to confirm the efficacy of IFRT in preventing patellar tendinopathy, the evidence is nonetheless encouraging given the lack of preventative patellar tendinopathy interventions available,54 and the high number of associated risk factors identified in jumping athletes.55 Despite the potential efficacy of IFRT as a multifaceted tool in the rehabilitation of patellar tendinopathy, current evidence may be limited to athletic populations and not generalizable to other populations, until further evidence emerges.

No studies have investigated IFRT in rehabilitation with any other tendinopathies, so no recommendations can be made for IFRT with any tendinopathy other than patellar at present. Although IFRT may have potential therapeutic benefits in the management of any tendinopathy, Achilles tendinopathy would seem an obvious choice as an immediate candidate for investigation. While eccentric training is recommended as a treatment for most tendinopathies, this method originated with eccentric calf raise training in Achilles tendinopathy,56 and currently the best evidence of clinical effectiveness of eccentric training is for Achilles tendinopathy, with a plethora of RCTs showing efficacy.57,58 Given IFRT is believed to exert clinical benefit and induce positive muscle and tendon adaptations through training with eccentric overload, it may have benefit as an Achilles tendinopathy treatment and should therefore be investigated in future research. Squat training utilising a flywheel squat device has been found to increase Achilles tendon cross-sectional area and the pennation angle of the medial aspect of the gastrocnemius muscle, suggesting eccentric overload training with flywheel devices is feasible for the Achilles tendon.59 Although the study by Sanz-Lopez et al.59 was conducted with healthy Achilles’ tendons and did not assess clinical benefit in Achilles tendinopathy, it serves to highlight the potential for positive Achilles tendon adaptations with IFRT, which may confer similar benefit to Achilles tendinopathy as seen with IFRT for patellar tendinopathy.

This review has several limitations, particularly the paucity of available research on IFRT for tendinopathy, with only four studies included, and only one RCT, highlighting the need for future high-quality studies with larger sample sizes. Future studies should also investigate the effects on specific subgroups known to be at increased risk for tendinopathy, including running as well as jumping athletes and the general sedentary population. Although the IFRT parameters implemented in studies were largely homogenous, there were some variances in sets, repetitions, and training frequency. Therefore, future studies should consider standardized methods and reporting of IFRT interventions in tendinopathy rehabilitation to enhance clinical translation of the research interventions. The longest follow-up times of included IFRT interventions were 12 weeks, with much longer follow up times required to assess the long-term adaptations and outcomes of IFRT in tendinopathy patients. Methods for monitoring and recording adherence to IFRT should also be emphasised in future studies as several included studies did not report the adherence level to IFRT, which may vary due to individual compliance, which may affect reported clinical outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Despite the paucity of research conducted to date on the effects of IFRT as a treatment option for tendinopathies, a small body of evidence is forming suggesting that IFRT may be an effective multifaceted tool at the clinician’s disposal, for use in the rehabilitation of patellar tendinopathy. While the evidence is preliminary, the included studies in this review all found beneficial clinical, physical, and tendon outcomes with IFRT in subjects with patellar tendinopathy. One high quality RCT has shown comparable efficacy for multiple outcomes to the currently considered gold standard method of HSRT. Further high quality RCTs with larger sample sizes are required to confirm the efficacy of IFRT in patellar tendinopathy and explore its efficacy with other tendinopathies such as Achilles tendinopathy. Evidence from studies included in this review, alongside the known scientific rationale for muscle and tendon adaptations with IFRT, is suggestive of potential clinical benefits as a tendinopathy treatment and possible alternative or compliment to current management methods.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

None declared.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.