INTRODUCTION

Evidence-based practice (EBP) was developed with the aim to translate the most updated, appropriate evidence to clinical practices.1 The EBP model consists of three components: scientific evidence from empirical research, clinical experience of healthcare providers, and fundamental values of an individual patient. A combination of the these three pillars is considered an important aspect in decision making.2 To enhance the EBP initiative, it was recommended to conduct research studies in the clinical setting where patients are present.3 Several studies reported positive clinical outcomes utilizing this approach.4,5 In this model, medical providers, also referred to as clinician-scientists, play an integral role as point personnel to translate research evidence to clinical practice. Although clinician-scientists are considered key personnel in the EBP model, they are also recognized as an “endangered species.”6,7 According to Roberts et al., there has been a decrease in the number of clinician-scientists as well as reduction in the research activity time among physicians.8

Several studies have been performed to identify reasons for the downward trend in research activities in clinician-scientists.3,9,10 According to the literature, a lack of available time, research knowledge, and administrative support were frequently reported.11–13 Additionally, some authors found that overall priorities for the research activities were different between physicians and allied healthcare (AH) practitioners.14,15 In summary, there are several known barriers to a clinician-scientist’s participation in research and the perception of research activities differs between physicians and AH practitioners.

In contrast, factors that facilitate research activities are understudied compared to research barriers. Moreover, studies that focused on research barriers and facilitators specifically in the field of sports medicine (SM) are limited. Identifying barriers and facilitators to research is an important first step to help optimize the research engagement of clinician-scientists in the SM community. Furthermore, as previous research identified differences in research engagement between physicians and AH practitioners,14,15 it is important to examine the research barriers and facilitators between the two healthcare professions in SM community. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine and compare research barriers, facilitators, and other research related components including interests, comfort, knowledge, and resources among SM physicians and AH practitioners.

METHODS

Study Design

A cross-sectional survey study design was employed. The recruitment strategy and the survey were reviewed and approved by the research ethics board of the host institution (Boston Children’s Hospital) prior to the initiation of this study.

Procedures

The survey, which consisted of research interests, perceptions, resources, barriers and facilitators, was developed by one clinician-scientist, a doctoral student, and a full-time researcher all who specialize in SM. The survey was reviewed by several SM physicians and AH practitioners prior to the dissemination. The survey was updated several times based on their feedback. The Pediatric Research in Sports Medicine (PRiSM) community was targeted as an initial source of participants to complete the survey. The main reason for selecting the PRiSM was that this organization is known as a multidisciplinary group in north America, mainly US, with members consisting of SM physicians (MD, DO) and SM specific AH practitioners including physical therapists (PTs) and athletic trainers (ATs). In this study, SM physicians were defined as those who held a Doctor of Medicine (MD) and/or a Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) degree, and individuals who held a physical therapy and/or athletic training license as AH practitioners. For analyses of the data from PRiSM members as a whole, all collected responses were included. For comparisons between SM physicians and AH practitioners, responses from those who did not have clinical duties, described as “others” were excluded from analyses.

Following approval from the PRiSM board, the on-line survey was disseminated to the PRiSM members via email in May 2020. To capture the survey responses, research electronic data capture (REDCap, Vanderbilt University, Nashiville, TN, USA) was utilized. After an initial email, a total of three reminder emails were subsequently sent to the PRiSM members to encourage participation. All emails were sent from the PRiSM headquarters to ensure that the survey was only delivered to the PRiSM members. An access to the survey link was available for three months (closed in August 2020). The REDCap system was programmed to compute binary variables, multiple choices, and proportional ratios such as percentages (%).

Respondents were asked to identify and rank three barriers and three facilitators that contributed most to their participation in research activities from 10-11 distinctively unique choices. Additionally, respondents were instructed to rate each component of the 10-11 choices with four scales, 1) to no extent, 2) to a little extent, 3) to a moderate extent, and 4) to a great extent, and an option of no opinion/not applied. Respondents were asked whether they were interested in research or not with binary manner (yes or no), and for those who answered “yes,” specific areas of research interests and actual research involvement were subsequently sought. Also, respondents were asked to give a self-rating of comfort reading research articles and their knowledge regarding conducting research independently with a 0-100 scale. For research resources, there were nine choices including 1) graduate students, 2) facilities for research, 3) residents, 4) research coordinator, 5) research technician, 6) biostatistician, 7) statistical/analytical software, 8) none, and 9) other, and respondents were requested to pick available resources.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures were barriers and facilitators of research activities. Secondary outcome measures were research interests, self-rated comfort reading research article, self-rated knowledge conducting research independently, and resources associated with research activities.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was used to analyze participants’ demographics. T-tests were used to compare continuous variables related to research perceptions between SM physicians and AH practitioners. Frequency of certain categories and ranks were expressed as percentages (%). For binary categorical variables such as research interests, 2 x 2 chi-square (x2) analyses were employed to examine proportional differences between SM physicians and AH practitioners. The a priori statistical significance level was set as p<0.05 for all analyses. The top three parameters of the primary outcome variables, barriers and facilitators, were selected and stratified between SM physicians and AH practitioners. IBM SPSS statistical software (Version 26, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Demographics

There were 100 responses (57 males and 39 females, missing sex responses: N=4). Response rate from PRiSM was 35.7%. Mean ages of participants were 42.5±10.7 (95%CI: 40.3, 44.7) years. Mean ages of males were 45.0±10.9 (95%CI: 42.1, 48.0) years, while females were slightly younger 38.9±9.5 (95%CI: 35.8, 42.0). About 86.6% of respondents reported spending 10 hours or more per week providing direct patient care. Also, 89.6% worked more than 15 hours per week at their primary medical care settings. Other demographics of the respondents including primary occupation, medical care settings, and geographic regions are presented in Table 1.

Furthermore, medical care settings of SM physicians and AH practitioners were examined. Medical care settings of SM physicians consisted of hospital (33.3%), hospital-based outpatient center (42.0%), private practice (15.9%), university (7.3%), and others (1.5%). Breakdown of care provision settings of AH practitioners were hospital (12.5%), hospital-based outpatient center (66.6%), university (12.5%), fitness center (4.2%), and others (4.2%).

Barriers and Facilitators

Results of the 10-11 choices related to research barriers with the four rating scales were listed in Table 2.

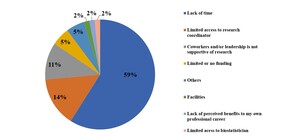

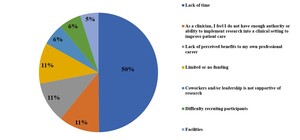

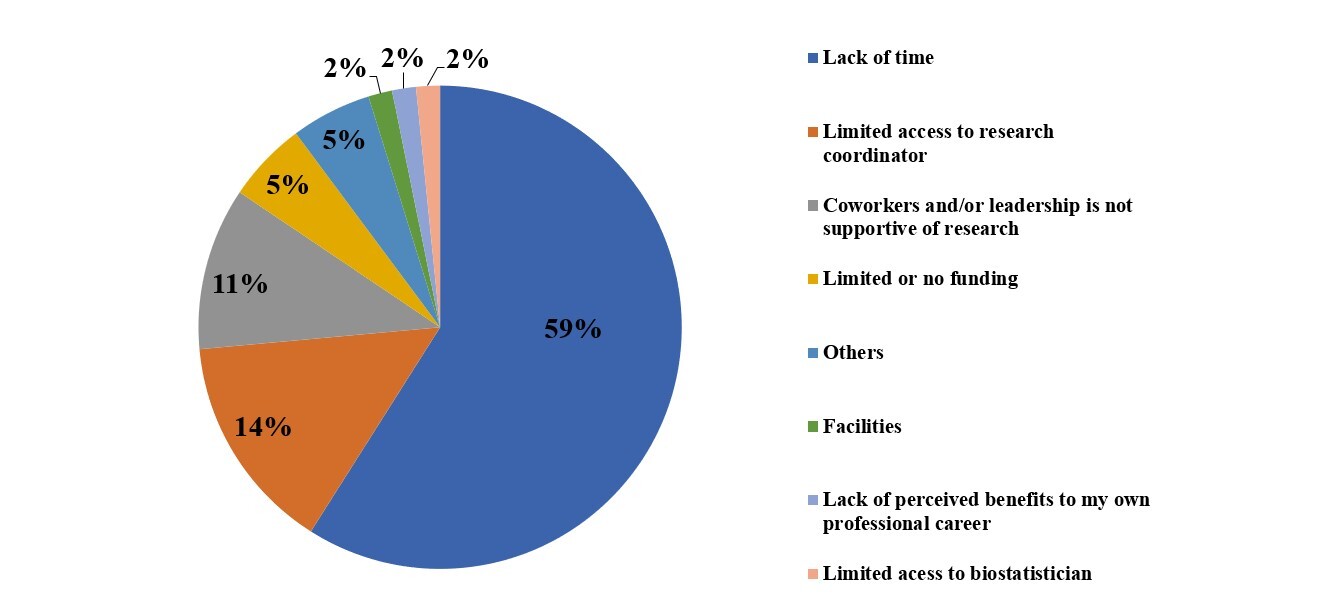

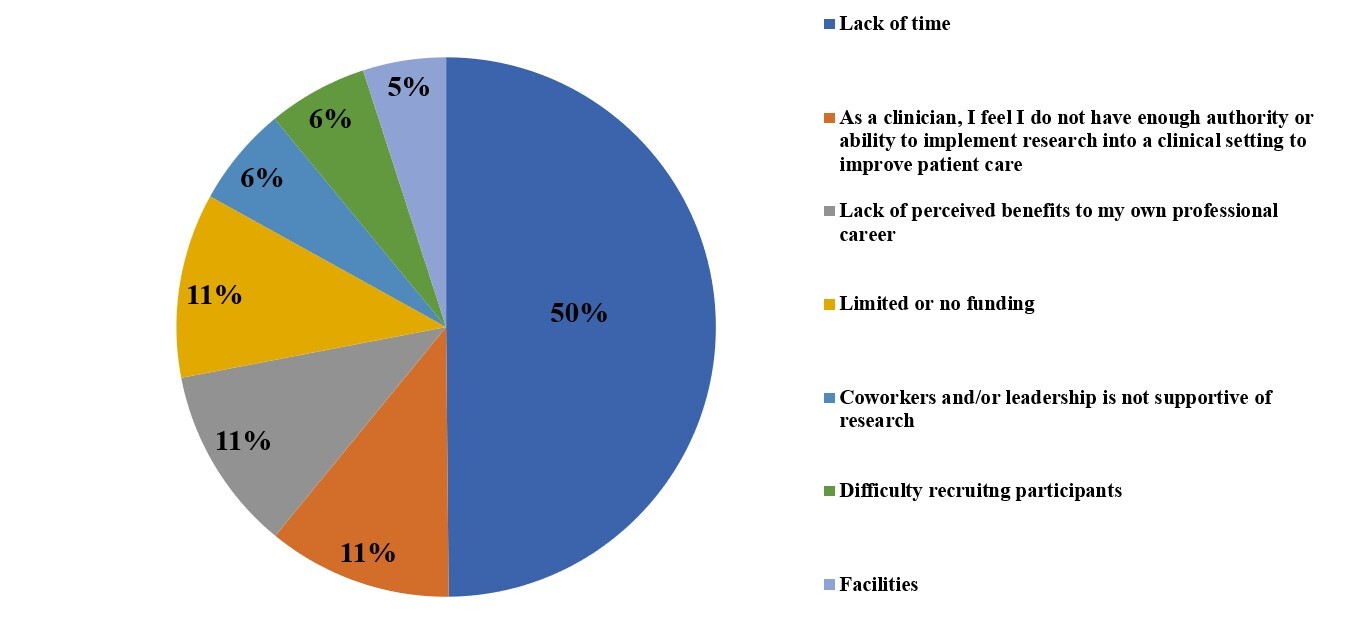

Among the 11 choices, the greatest barrier for research activity was a lack of time (28.3%). The research barriers were further stratified by SM physicians and AH practitioners. The top selection of the research barriers was the same between the two medical professions: a lack of time (Figures 1, 2). However, other reported barriers differed between SM physicians and AH practitioners (Figures 1, 2).

Similarly, 10 choices related to research facilitators were assessed by four rating scales and the outcomes were found in Table 3.

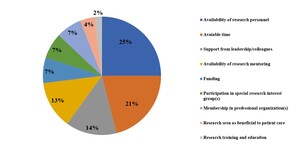

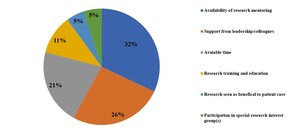

In the 10 choices, the leading research facilitator was available time (18.5%). Moreover, research facilitators were analyzed separately between SM physicians and AH practitioners (Figures 3, 4). The top research facilitator for SM physicians was availability of research personnel, while availability of research mentoring was selected as the top facilitator in AH practitioners (Figures 3, 4).

Interests in Research Activities

About 88.7% of respondents expressed an interest in research, while 11.3% chose no research interest (missing responses, N=3). AH practitioners showed higher research interest (95.5%) compared with SM physicians (87.0%), but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.267). The specific areas of research interests were presented in Table 4. Additionally, actual research involvement is also displayed in Table 4.

Comfort, Knowledge, and Resources

Regarding self-rated comfort in reading research articles, overall mean was 72.0±23.6 (95%CI: 67.2, 76.8) using a 0-100 scale (missing responses, N=5). In comparison between SM physicians and AH practitioners, the mean value was higher in SM physicians [75.6±20.6 (95%CI: 70.6, 80.6)] compared with AH practitioners [60.6±28.3 (95%CI: 47.0, 74.3)] (p=0.018). Additionally, overall mean score of self-rated knowledge regarding conducting a research study independently was 68.4±20.5 (95%CI: 64.2, 72.5) using a 0-100 scale (missing responses, N=6). The mean value of the self-rated knowledge conducting research in SM physicians was 70.2±18.6 (95%CI: 65.7, 74.7), while AH practitioners demonstrated a score of 63.4±24.6 (95%CI: 51.5, 75.2) (p=0.163). Available resources to perform research activities as a whole and by each profession are shown in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

The current study investigated barriers and facilitators to research, as well as other research related components including interests, comfort, knowledge, and resources among SM physicians and AH practitioners. According to our data, both SM physicians and AH practitioners identified a lack of time as the top barrier to research participation (Figures 1, 2). However, the remaining top research barriers were different between the two professions. The second and third most common research barrier identified from SM physicians were limited access to a research coordinator and having co-workers or leadership that is not supportive of research. This finding indicated the importance, for SM physicians, of having access to valuable research staff as well as support from peers and leadership. Conversely, the second and third barriers in AH practitioners were apparently related to a negative mindset/outlook toward research.

AH practitioners who participated in the current study were PTs and ATs. Since investigations related to research barriers and facilitators of PTs and ATs were understudied, available studies related to another group of AH practitioners, nurses, were synthesized.16–19 A few studies indicated that the negative mindset/outlook toward research activities may stem from a clinical hierarchy between physicians and nurses.16–18 The authors of these studies described that nurses were not ranked or positioned to change clinical practices within the clinical setting.16–18 They postulated that a lack of autonomy in the clinical setting may negatively influence research interests and activities.16,18,19 This description aligns well with the current study findings (Figure 2). About 11% of respondents from the AH practitioners in the current study showed disbeliefs and/or doubt of having enough authority or ability to implement research into a clinical setting to improve patient care. Additionally, another 11% of respondents from the AH practitioners did not perceive research as being beneficial to their own professional career. This may be related to another barrier, coworkers and/or leadership is not supportive of research, among the AH practitioners (6%). In fact, one study discussed that an underlying major research barrier was a lack of research support from leadership.3 This lack of research support from leadership stemmed from the culture of the AH practitioners work environment.3 According to this report,3 direct patient care is usually perceived as a primary responsibility, and research activity was often viewed as secondary or as a non-essential task in AH practitioners.3 The primary job of both PTs and ATs is, indeed, direct patient care, and therefore, if research is perceived as a non-essential task, this will likely contribute to the perceived lack of benefit that PTs and ATs feel toward spending time engaging in research activities.

Research facilitators were distinctively different and unique in each profession (Figure 3, 4). Among SM physicians, availability of research personnel was the top facilitator (25%) followed by available time (21%). Underlying reasons of these facilitators may stem from a special role a few SM physicians often take. One unique role of SM physicians is to work as a local sports team doctor.20,21 The responsibility of working as a team doctor is considerably comprehensive, especially for a collision sport such as American football,22,23 and for some high-profile teams, traveling with the team is also a part of the job.24 In short, serving a team physician to local sports teams is a time-consuming commitment, which explains the reason why availability of research personnel to facilitate research activities is extremely important. Furthermore, SM physicians reported being are more comfortable reading research articles than AH professionals and reported a higher self-perceived ability to conduct research independently (although not statistically different) as compared to AH practitioners. Therefore, having access to available research personnel may be a key factor to the promotion of research activities within their limited time.

Unlike selections of SM physicians, availability of research mentoring (32%) and support from leadership/colleagues (26%) were chosen as leading facilitators from AH practitioners. The importance of available time as a research facilitator has been previously documented by various authors.3,25–27 However, the availability of mentoring and support from leadership/colleagues as primary facilitators expressed by PTs and ATs has not been previously reported. This alone is an important finding to highlight, indicating the current lack of mentorship or support from leadership among AH professionals. This concept should be considered moving forward when evaluating and discussing barriers and facilitators in SM research. Yet, it is essential to recognize that this finding may also be unique to the field of SM, given the prevalence of PTs and ATs in this community. Furthermore, although not statistically significantly different, AH practitioners showed greater research interests (95.5%) than SM physicians (87.0%), especially with regards to research design/protocol development and data collections, while having less access to a research technician and a biostatistician. These findings emphasize the importance of providing support to further facilitate research activities in AH professionals.

A potential solution to overcome the identified barriers and nurture the facilitators may be to develop those who have a role as researcher associates. In this study, 7% of the survey respondents did not have clinical duties and were labeled “others”, and their primary responsibilities were associated with research activities. Since a lack of time was the top barrier for both SM physicians and AH practitioners, collaborating with research associates (others) may help save time and facilitate participation. For instance, pivotal research activities such as preparing IRB documents, analyzing collected data, and drafting scientific manuscripts often take substantial time. However, research associates may be able to optimize these steps and shorten the time in each step. Additionally, availability of research personnel was found as a leading facilitator in SM physicians, and research associates are an ideal candidate to fill their needs. Furthermore, availability of research mentoring was selected as the greatest facilitator in AH practitioners. Developing a mentor-mentee relationship with established researchers may help enhance research productivity of AH practitioners. In summary, leadership and/or administrators should investigate promoting and solidifying a collaborative relationship among SM physicians, AH practitioners, and research associates.

Limitations

Several limitations need to be stated, with a main limitation being that the current study data were obtained solely from the PRiSM membership. Clinicians and practitioners who are in societies such as PRiSM, are likely to already have positive perspectives on research, and thus introduce a potential bias in the study findings, especially as involvement is typically on a volunteer basis. Regardless, this preliminary assessment into barriers and facilitators is an important first step in capturing the current state of research participation among members in the SM community. Furthermore, although the current study had acceptable response rate (35.7%), an overall number of survey respondents was 100, which is a relatively small sample size. Also, nearly all members were geographically located in the US and Canada. Thus, the results may not be generalized to other regions or continents of SM physicians and AH practitioners. Additionally, responses from AH practitioners (24%) were lower than SM physicians (69%). Moreover, approximately 9% of respondents had additional degrees such as a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Masters of Public Health (MPH), and Masters of Science (MSc). Some respondents may be using those degrees as their primary responsibility/function in their institutions. Lastly, the survey was programmed to be sent to each of the PRiSM members only once. To avoid confusion and errors, the survey was directly delivered from the PRiSM headquarters to all PRiSM members. The collected responses were rigorously checked. However, the possibility of responses from non-members and potential duplicates (multiple responses from one member) could not be eliminated.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicate that a lack of time was the top research barrier for both SM physicians and AH practitioners. Research facilitators were different between SM physicians and AH practitioners. Having available personnel was the main facilitator for SM physicians, while availability of mentoring was the leading facilitator in AH practitioners. Those who take a leadership position in a SM department may need to be aware these findings, especially if enhancement of research productivity is priority. Future studies are warranted to investigate other parameters to optimize evidence-based practices.

Disclosure of Funding Source

None

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.