INTRODUCTION

The knee is the most commonly injured joint in both male and female adults, accounting for 19% to 23% of all orthopedic injuries.1 Two of the most frequent musculoskeletal knee conditions are anterior knee pain (AKP), which incorporates patellofemoral pain, patellar subluxation, and patella dislocations, and anterior cruciate ligament injuries (ACL).2–4 AKP has an annual prevalence of 22.7%5 while over 250,000 ACL injuries occur each year.6 AKP is a multifactorial pathology linked to increase stress on the patellofemoral joint, resulting in pain,7 and recurrent or chronic symptoms.3 ACL injuries are often the result of direct or indirect trauma to the knee, often leading to surgical intervention (e.g., reconstruction) to restore stability and function of the knee.8 While the mechanism of injury between conditions differs, both present with similar clinical impairments. Individuals with AKP and ACL reconstruction (ACLR) often present with decreased self-reported function,7 lower extremity muscle weakness,7 reduced physical activity level7,9,10 and poor health-related quality of life.11,12 Additionally, both AKP13 and ACLR14 are suggested to result in increased risk for the development of knee osteoarthritis.

Although therapeutic interventions and surgical procedures aim to enhance physical function in individuals with AKP and ACLR, many individuals still report long-term disability.8,15 Restoration of functional outcomes and patient-reported satisfaction is one of the primary criteria for medical clearance for return to daily activities following knee pathologies.16–18 Unfortunately, many patients exhibit psychological impairments during their rehabilitation that can act as barriers to successful recovery.19 Both individuals with AKP and ACLR present with injury-related fear-avoidance, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing.20–22 Greater psychological barriers in both patient populations has been associated with inability to resume pre-injury levels of sport, decreased physical activity engagement, and decreased health- or knee-related quality of life.8,23 Fear-avoidance is based off a psychiatric model that describes how individuals develop and maintain musculoskeletal pain as a result of avoiding behavior based on past pain experiences.24 Kinesiophobia is generally defined as fear of movement due to the pain experience25 whereas pain catastrophizing is depicted as magnifying pain and feeling helpless in the face of pain.26

Self-reported questionnaires to quantify psychological barriers have emerged as an important component for AKP11 and ACLR27 rehabilitation. These tools are frequently integrated into return to play testing with psychological barriers being predictive of athletes success in returning to sport17,28 and regaining optimal physical function.29 In recent literature, the decision to return to sport after ACLR has been strongly influenced by psychosocial factors.30 Additionally, elevated fear-avoidance beliefs and fear of reinjury are associated with increased risk of injury, impaired return to prior levels of performance, and reduced physical activity level.9,31–34 Over time psychological barriers and physical performance improve; however, the improvements do not exceed clinical thresholds and still present years following injury and treatment.35–37 This reinforces that physical performance should not be the lone post-operative outcome and that consideration of psychological consequences in those with knee pathologies should also be accounted for.30 Psychological characteristics amongst AKP and ACLR patient populations have been reported separately; however, it is unknown if similar psychological responses exist between two common knee conditions.

A comprehensive understanding of the psychological features in individuals with AKP and ACLR would help clinicians to develop and implement better treatment strategies to address deficits that may exist in these individuals. Therefore, the primary purpose of this study was to evaluate fear-avoidance, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing in individuals with AKP and ACLR compared with healthy individuals. The secondary purpose was to directly compare psychological characteristics between the AKP and ACLR groups. We hypothesized that 1) individuals with AKP and ACLR would self-report worse psychosocial function than healthy individuals and 2) the extent of the psychosocial impairments between the two knee pathologies would be similar.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

A survey was used to examine the influence of AKP and ACLR on fear-avoidance beliefs, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing. Independent variables include each group: AKP, ACLR, and a no injury history group. Dependent variables include the fear-avoidance belief questionnaire (FABQ) with the physical activity (FABQ-PA) and sport (FABQ-S) subscales, Tampa scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK-11) and pain catastrophizing scale (PCS) scores. The reporting of the study adhered to the CHERRIES guidelines recommendations.38 The study was approved by each university’s Institutional Review Board (University of Connecticut and University of Toledo) and all participants provided informed consent via an online consent process. Participants were provided information regarding study purpose, estimated time for study completion, management of identifiable data, and contact information for the research team. Cookies or timestamps were not used in this study but duplicate IP addresses were extracted.

Procedures

Data were collected over an eight-month period from two large public universities (one in the Midwest and one in the Northeast) from college-aged students as part of a larger study evaluating musculoskeletal injury history. Recruitment for the study was conducted electronically via email, social media platforms, and research announcements at each university. A total of 502 participants between the two universities completed a survey, 83 participants met the purpose of this study and were included in this analysis.

Participants completed a self-reported injury history questionnaire. The injury history questionnaire was derived from previously reported measures and included 15 categories of sports-related injuries.39 Participants were asked to self-report if they had previously sustained any musculoskeletal conditions The questionnaire also collected basic demographic information (e.g., height, weight) and if participants were currently experiencing an injury that was resulting in pain. Participants who reported a previous musculoskeletal condition were also asked to indicate additional demographic information about the type and severity of injury, whether surgery was required, the number of times the injury occurred, and time since injury/surgery. All participants, regardless of injury status, then completed three previously validated patient reported outcome metrics developed to capture psychological function after musculoskeletal injury. The included the FABQ-PA, FABQ-S, TSK-11, PCS in an online data management system (Qualtrics). We adhered to previously described methods that no time restrictions were instituted for either AKP or ACLR history and included any self-reported knee injuries.40 Finally, the last question of the survey inquired about fear surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic.

The FABQ was developed as a 16-item dimension specific questionnaire that originally measured fear-avoidance beliefs related to physical activity and work in individuals with low back pain.41 A modified FABQ was utilized that replaced “low back” with “knee” in order to be joint specific in addition to modifying the work subscale to the sport subscale.18 The physical activity subscale (FABQ-PA) includes six questions that are scored out of 30 points while the sport subscale (FABQ-S) includes 10 questions that are scored out of 60 points. Greater scores reflect increased fear-avoidance beliefs related to physical activity and sport. The modified FABQ physical activity and sport subscales have acceptable internal consistency in individuals with a history of knee injuries.42

The TSK-11 is an 11-item dimension specific questionnaire that is used to measure kinesiophobia. The TSK-11 ranges from 11 to 44, with greater scores reflecting greater fear of movement and reinjury due to movement. The TSK-11 has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency (0.79) and reliability (0.81) in a chronic low back pain population.43 The TSK-11 has also been reported across various knee injury populations, including ACLR.44

Pain catastrophizing was measured with the PCS, which is a 13-item dimension specific questionnaire. The PCS ranges from 0 to 52, with greater scores representing greater catastrophic pain. The PCS has good to excellent test-retest reliability (ICC=0.88-.90), adequate validity (0.40-0.42) and excellent internal consistency (0.92).45 A total score above 30 indicates clinically relevant level of catastrophizing.

Participants were extracted based off who previously reported history of either AKP and/or ACLR and then extracted a third group of individuals without a history of musculoskeletal injury. AKP was defined as patellofemoral pain, history of patella subluxation / dislocation, or patella maltracking, but did not include patellar or quadriceps tendinopathy. Participant responses were excluded for missing data of the health history form or questionnaires. A total of 83 participants were included: 28 participants (13 males and 15 females) with a history of AKP, 26 participants (11 males and 15 females) with a history of ACLR and 29 participants (11 males and 18 females) without a history of musculoskeletal injury (i.e., healthy individuals).

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software (V.22; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) was used for all statistical analyses. We assessed normality of data with a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which identified non-normally distributed data. Separate Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare the FABQ-PA, FABQ-S, TSK-11, and PCS scores across the three groups (AKP, ACLR, Healthy). Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to determine where group differences occurred. We calculated non-parametric effect sizes to determine the magnitude of difference between groups for all questionnaires. Effect sizes were calculated with the Mann-Whitney U z-score divided by the square root of the group size. Effect sizes were interpreted as small (|0.10-0.29|). medium (|0.30-0.49|), and large (|≥0.50|).46 Descriptive statistics for all four questionnaires (FABQ-PA, FABQ-S, TSK-11, and PCS) were reported as medians, along with 25% and 75% interquartile ranges. Alpha for all analyses was set a priori as p≤0.05 meaning there is a 5% chance that the significant findings were due to error.

RESULTS

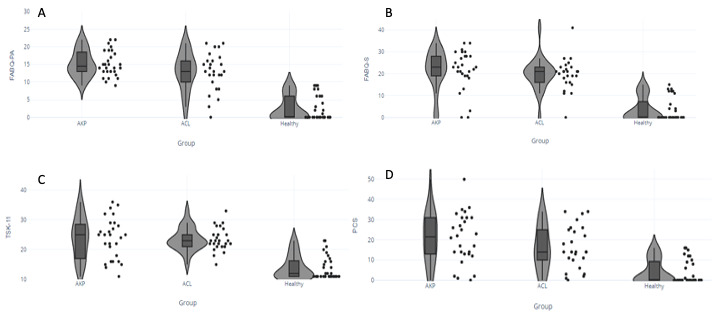

Descriptive demographics between groups are reported in Table 1, and there were no differences in age or sex across the three groups, p=0.72. The AKP group included 15 cases of patellofemoral pain, 10 cases with history of patella subluxation (n=7) or dislocation (n=3) and one case of patella maltracking. There was a significant interaction effect between injury history and questionnaire (FABQ-PA, FABQ-S, TSK-11, and PCS) interaction effect present, p<0.001 (Table 2). Participants with a history of AKP or ACLR had significantly worse scores compared to the healthy group for all questionnaires; however, there were no differences between the AKP or ACLR groups (Figure 1).

There were large magnitude effect sizes with the healthy versus AKP (ES= -1.20 to -0.94) and healthy versus ACLR (ES= -1.06 to -0.86) group comparisons. There was a medium effect size (ES= -0.33) in the FABQ-S between the AKP and ACLR groups, but small effect sizes for the remaining questionnaires (ES= -0.27 to -0.08).

DISCUSSION

College-aged individuals with a history of AKP or ACLR report elevated fear-avoidance, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing compared to healthy individuals. There were no statistical or clinically meaningful differences in fear-avoidance, kinesiophobia, or pain catastrophizing between AKP and ACLR groups; however, there was a medium effect that individuals with AKP had a greater FABQ-S score compared to the individuals with ACLR.

AKP and ACLR groups exhibited greater scores in the FABQ-PA, FABQ-S, TSK-11 and PCS compared to the healthy group, which is consistent with previous literature. The findings emphasize the importance of assessing psychological factors in patients with knee pathologies, as various constructs may be present throughout the rehabilitation process.28,47 Both the AKP and ACLR groups had elevated scores across the four questionnaires but did not differ statistically between groups; however, there were small-to-moderate clinical differences in the FABQ-PA, FABQ-S and PCS scores.

There was a wide range in scores across the AKP and ACLR groups for all four psychological scales (Figure 1). Clinical thresholds have been established for three of the four included questionnaires to identify individuals with elevated fear-avoidance beliefs, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing. A threshold score of 15 on the FABQ-PA47 is used to identify individuals with elevated fear-avoidance beliefs while a score of 30 on the PSC26 quantifies pain catastrophizing. The TSK-11 has been divided into four subgroups: minimal (≤22), low (23-28), moderate (29-35) and high (≥36). Fourteen individuals (50%) with AKP exceeding the threshold for having elevated fear-avoidance beliefs, but more interestingly, no individual with AKP scored below a 9 on the FABQ-PA (Figure 1). This differs from the ACLR group who did not exceed threshold values fear-avoidance beliefs on the physical activity scale, suggesting that fear-avoidance beliefs might be more common in individuals with AKP. The fear-avoidance model may help explain these findings, as the recurring chronic pain may provide individuals with AKP more opportunities to confront or develop fear of their pain. However, it is difficult to determine if the fear-avoidance model contributes to this phenomenon without longitudinal data exploring severity and frequency of pain, physical activity level, return to sport or other factors that may contribute to fear of pain. Similar trends in the other scales were observed, with a greater number of individuals with AKP demonstrating moderate to high kinesiophobia (eight individuals with AKP compared to three ACLR individuals) (Figure 1c) and exceeding pain catastrophizing (eight individuals with AKP compared to four ACLR individuals) (Figure 1d). The small-to-moderate clinical differences in fear-avoidance beliefs and pain catastrophizing scores in the AKP group may be due to the included cohort. The AKP cohort mainly included individuals with patellofemoral pain, which results in pain during functional tasks that require knee flexion and lasts for years after initial diagnosis.23,48 Additionally, almost half of our AKP cohort were still experiencing pain at the time of survey completion, which may explain why they had greater psychological barriers.

Although both groups reported greater fear related beliefs compared to the healthy group, there was no statistical differences between AKP and ACLR groups. Therefore, regardless of knee pathology, individuals may benefit from psychological interventions to combat increased fear-avoidance, kinesiophobia, and catastrophic pain. Despite the lack of differences between groups, interventions are essential to minimize secondary consequences and poor long-term implications associated with elevated psychological domains. The fear-avoidance model shows the longitudinal influence of psychological status on outcome where elevated pain catastrophizing and fear of movement or reinjury led to a more chronic disability.49 Individuals with increased fear-avoidance may also be at an increased risk for physical inactivity by adapting strategies to minimize painful stimuli.7 Additionally, greater levels of fear-avoidance are associated with stiffened movement patterns, reduced knee, hip and trunk flexion,50 that may predispose individuals to secondary injuries and readiness to return to sport.51 To address the long-term consequences and improve outcomes, clinicians must assess psychological domains and integrate appropriate interventions for patients suffering from injury regardless of injury type. There are various interventions that clinicians may prescribe when treating psychological impairments in their patients, such as relaxation therapy, guided imagery, goal-setting, and cognitive behavioral therapy.52,53 Psychologically informed interventions have been beneficial at reducing FABQ-PA, TSK-11, and pain catastrophizing in adolescents with PFP,54 while in vivo exposure therapy reduces injury related fear in ACLR cohort.55 Additionally, pain neuroscience education for chronic musculoskeletal conditions reduces psychosocial factors and improved movement impairments.56 While there is limited research directly comparing interventions across AKP and ACLR groups, the lack of difference in psychological variables from our data suggests multiple interventions may be beneficial to patients with knee related injuries.

Interestingly, the healthy group had individuals who responded to some questions, resulting in scores above zero on the FABQ-PA, FABQ-S and PCS, and greater than 11 on the TSK-11. While individuals responded to some questions across the scales, most did not exceed the threshold scores that signify clinical classification. No healthy individuals exceeded the threshold for elevated fear-avoidance belief on the FABQ-PA.47 Two healthy participants would be classified as low kinesiophobia, scoring a 23 on the TSK-11, while the remaining 27 healthy participants would be classified as minimal kinesiophobia.57 Finally, no healthy participants exceeded the clinical threshold on PCS. Another possible explanation would be that the study was administered during the COVID-19 pandemic, which could account for the responses within the healthy individuals.58 Fear and stress are common responses when individuals are exposed to perceived threats or during uncertainty, which were common due to the pandemic. Fear and stress increased during the pandemic,59 which may impact both our pathological and healthy groups when completing fear-based questionnaires such as those included in our study. The final question in the survey inquired if participants had increased anxiety levels or depression due to COVID-19; however, there were significant differences depending on question responses.

While some relationships exist across psychological domains, fear-avoidance beliefs, kinesiophobia and pain catastrophizing are distinct constructs. Similar scores were observed in the FABQ, TSK-11 and PCS between both the AKP and ACLR groups; however, the selection of questionnaires may be specific to the type of pathology.60,61 Decreasing fear-avoidance beliefs specifically on the FABQ-PA, predicts function and pain of a standard intervention program in individuals with AKP. Additionally, lower pain catastrophizing four-weeks after ACLR were associated with better knee function 12-weeks post-surgery,35 while greater kinesiophobia increased the odds of identifying patients at risk for delayed progression in their rehabilitation program. The integration of psychological questionnaires in clinical practice may be a viable approach to predict success of traditional intervention programs or identify patients who warrant psychological interventions.62 These findings provide a baseline look into fear-avoidance beliefs, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing; however further investigations are needed to determine if the scales selected correlate with responses from various intervention programs.

This study is not without limitations. Due to the perceptual scales and injury history questionnaire being self-reported, there is a risk of missing injuries or recall bias. We also did not acquire detailed data regarding pain severity or time since pain/injury which may influence these results. Patient reported outcome measures selected in this study may have been influenced by time since surgery and recurrent bouts of pain. Differences exist between the clinical presentation and duration of impairments between AKP and ACLR. Patients experiencing AKP have pain for years after diagnosis, suggesting greater duration of pain may provide more opportunities for the development of fear-avoidance behaviors. Additionally, within the ACLR group time since injury also may have influenced the results along with comorbidities associated with an ACL injury. Frequency of injuries was not controlled, which may have a compounding effect on the reported scores. Current physical activity was also not assessed, which may influence symptoms or psychological impairments in the included populations. Injury history within our participant recruitment was also not accounted for, which reduces the interval validity. However, this choice improves the external validity, as clinicians often treat individuals with ACLR or AKP that have experienced previous musculoskeletal conditions. Similarities in the number of participants with previous conditions between each group were not analyzed. Finally, there should be some caution with the generalizability of the findings, due to the cohort only including college aged individuals and the participants self-reporting their injury history.

CONCLUSION

College-aged individuals with a history of AKP or ACLR demonstrated greater fear-avoidance beliefs, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing than healthy controls. There were no differences across the four questionnaires between individuals with AKP or ACLR, suggesting that despite the difference in the knee pathologies, psychological responses may be similar. Clinicians should be aware of fear-related beliefs following knee-related injuries and are encouraged to measure psychological factors during the rehabilitation process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.