Introduction

Hip osteoarthritis (OA) is becoming increasingly prevalent, with a total increase of 115.40% for the global incidence of hip OA from 1990 to 2019.1 OA is a chronic degenerative joint disorder and is the most common reason for total hip arthroplasty (THA) surgery in Australia.2 Due to its debilitating effects and impact on quality of life, OA is the world’s fourth leading cause of disability.3 THA has been shown to be a beneficial treatment as it offers relief from pain, improves function, and subsequently improves quality of life.4 The number of THAs being performed every year is increasing with a forecasted increase of 208% from 2013-2030. By 2030, THAs are expected to cost Australia $953 million.5

Many types of THA surgical techniques exist and there is much debate over which technique is most effective. The direct anterior approach has been associated with numerous claimed benefits such as reduced hospitalization periods, diminished risk of dislocation, reduced blood loss, and reduction of postoperative pain. As a result, it is a preferred method due to its minimized muscle disruption, smaller incision, and fewer post-surgical precautions in comparison to alternative approaches.6 As this technique facilitates faster recovery, a heightened emphasis is being placed on post-operative hypertrophy muscular training to enable prompt return to work or sports. Hypertrophy muscular training is a form of strength training that concentrates on increasing muscle size and mass. This objective is achieved by applying controlled stress and resistance to the muscles, prompting the increase in size and number of muscle fibers resulting in an increase in muscle size alongside strength development. This is important as the size or mass of muscles play a large role in the rate of force development and muscle power.1 Current research highlights the postoperative decrease in cross-section of the surrounding musculature of the hip joint,7 indicating that a carefully structured exercise regimen designed to stimulate the enlargement and growth of muscle tissue surrounding the hip joint may be beneficial subsequent to THA.

While THA is not a relatively new procedure, it is apparent that there is little to no available research on the role of muscular strengthening/hypertrophy in the recovery from THA using the direct anterior approach with individuals seeking to return to physically demanding activities such as sports, manual labour and weight training. Hence, comparisons of muscle strength between anterior minimally invasive surgery (AMIS) procedures and the traditional THA approach remain speculative. The reported strength losses for various muscle groups in the operated leg following THA further contribute to this speculation.8 Holstege’s study indicates strength losses in hip abduction, adduction, flexion and extension as well as knee extension and flexion exist both pre- and post-operatively.9 These measures were taken after the out-patient rehabilitation period, for which documentation and quality of strengthening exercises is reliant on patient reporting and motivation. While the anterior approach and minimally invasive procedures reduce the level of soft tissue damage there is still very little research on the pattern of recovery of these muscles and even less on the rehabilitation process. Thus, the purpose of this review was to investigate the current guidelines and/or protocols for hypertrophy or strengthening in individuals who have undergone total hip arthroplasty.

Methods

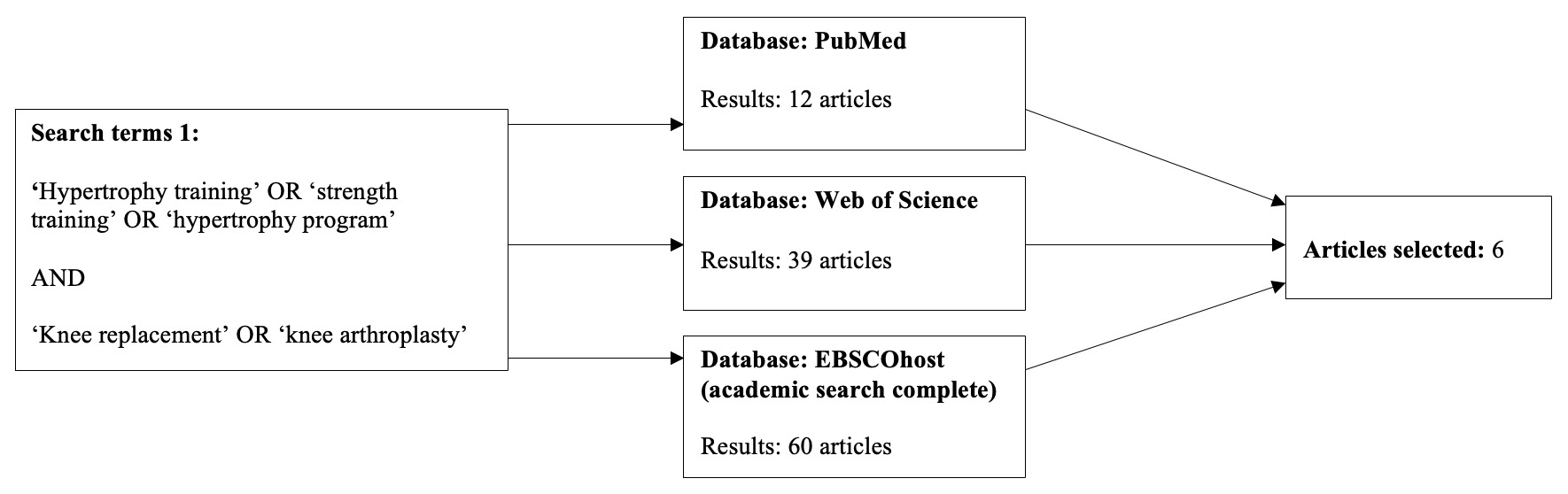

This search was conducted for relevant articles published in Pubmed, Web of Science and EBSCOhost, Original search terms included total hip replacement or arthroplasty, and terms for rehabilitation, such as strength or hypertrophy training (Figure 1a). To further expand the scope of this literature search, hypertrophy training and total knee replacement (TKA) surgery were also included (Figure 1b). TKA studies were added as the knee joint provides uniplanar angular motions in one direction within the sagittal plane. Similarly, the hip joint also provides an identical motion within the sagittal plane. As both joints impact the kinematics of the lower limb through compound movements such as squatting, and bridging, recent research into post-surgical joint arthroplasty rehabilitation has presented similarities among exercise prescription of both joint groups.10 Thus, to gain further insight and overcome the research gap in post-surgical hypertrophy protocols for the hip, the authors decided to include post-surgical TKA hypertrophy protocols into the search. Compound movements such as the leg press and hip abduction in seating have been shown to be effective in both hip and knee hypertrophy protocols thus providing grounds to take these studies into consideration.

The inclusion criteria were articles published since the year 2000, including randomised controlled trials, cohort designs, and case control design. To narrow down further, hypertrophy protocols had to be of high quality whereby program duration, chosen exercises and dosage was detailed. Articles were excluded if they were published earlier than 2000, published in a language other than English, or articles that were meta-analyses, systematic or literature reviews. See Appendix 1 for the full search strategy.

Results

A total of 1112 results were obtained through this search across three databases, upon evaluation, 16 relevant, but diverse hypertrophy programs were selected across varied time frames, dosages, exercise prescriptions, and levels of supervision. 10 THA studies and 6 TKA were identified that incorporated hypertrophy-based strengthening programs. Of note, only one of the ten studies, targeted hypertrophy in the context of returning to sport.11 Throughout this literature review, there was no program consensus amongst all the studies and programs to target THA post op muscle atrophy. As such there were also no consistent outcome measures to provide comparison between different programs and suggest one over another.

Table 1 provides the full results.

Among the 16 studies reviewed, four concluded no significant increase in strength compared to that of their control or standard post-surgical protocol. Although training duration and dosage varied within either the hip and knee studies, a significant increase in either strength and or functional performance was achieved within 13 of these studies.

Muscle strength

Among the 16 studies encompassing both the hip and knee arthroplasty, 13 of the 16 studies exhibited a substantial enhancement in muscular strength, while the remaining three studies indicated no statistically significant differences. A common trend within these studies was the utilization of a one-repetition maximum (1RM) assessment. This assessment method seemed to guide clinicians in determining optimal loads for individual patients by establishing a baseline for subsequent strengthening.

Exercise protocol

A diverse range of exercises were prescribed within each hypertrophy protocol. Similarities were found among numerous protocols within each of the hip or knee categories which can be found within Table 2.

The exercises with the highest prevalence among hip rehabilitation protocols included leg press, hip abduction, and hip extension in a standing position. In knee extension protocols, leg press and knee open kinetic chain extension were the most commonly used.

Discussion

A search through the available literature surrounding the rehabilitation process of THA reveals a high amount of variability in programming, outcomes, durations, and level of supervision with regards to resistance training and muscle hypertrophy. Similar outcomes are seen in the TKA literature.

Many of the studies lacked specificity in their exercise intensity prescriptions neglecting any kind of 1RM testing. Without accurate measures of intensity, hypertrophy adaptations may be diminished as well as limit the reproducibility of the exercise parameters. Commonality was found in studies whose programs revolved around hip abduction and leg press as their key exercises.8,9,12,13 Logical movements targeting hypertrophy of gluteal musculature are required due to this muscle group being most affected by currently utilized surgical approaches.14 While the populations, methods, and durations of the selected studies naturally vary depending on individual research aims, outcome measures, and interventions, what became clear is that there is no consensus rehabilitation protocol to be adapted to or followed for patient hypertrophy following THA.

Husby15,16 implemented hip abduction and leg press strength-based programs from one week post op to weeks four and five post op in two studies. Both utilized 1RM testing to inform individual exercise prescription intensities, thus maximizing the benefits of resistance training without overexerting. Collectively these RCT’s indicated that early maximal strength training combined with conventional rehabilitation showed improvements in patients’ muscular strength, work efficiency, and in particular, rate of force development (RFD) which improved by 74% 12 months post op compared to control/conventional rehab.16 However, further long-term studies are needed to investigate this type of training model with younger patients returning to vigorous physical activities, sports, and manual labour post op.

Conversely Madara11 and Mikkleson17 both conducted longer-term studies studying supervised versus unsupervised rehabilitation. Mickleson reported improvements in patient satisfaction and strength outcomes in the intervention group who used home resistance training versus conventional rehab, but concluded that even the more strenuous program resulted in insufficient strength gains on the operated side versus non operated side. Results were limited by suitability of exercises for all participants. Madara’s feasibility study involved participants going unsupervised with a home program for the first six weeks and then PT supervised rehabilitation for the last 10 weeks tailored to the patients’ goals and potential return to sport desires. The experimental group recorded statistically significant increases in 6MWT, rehab satisfaction, and improvements in between-limb force symmetry during sit to stand tasks. While these studies individually have limited statistical power, when considered together they may suggest that a robust, supervised, resistance training based protocol may provide the most benefit to THA patients to minimize post op strength deficits, return to sport, and achieve patient-centred goals.

Two exploratory studies examined the impacts of progressive overload using 1RM testing, the first13 focusing on pain and progression after TKA and THA during early-initiated modified strength training and the second18 examining the impact of leg press, hip abduction/knee extension resistance training on postural sway in THA patients. In the first study both TKA and THA patient’s pain levels were not beyond moderate levels with increased early load progression post op, albeit TKA predictably higher than THA. Both groups statistically significantly increased loads each week until the second to last week (TKA) and last week (THA) of the study resulting in a 120-130% increase in leg press training load by week eight. While study power was limited by small sample sizes and incomplete pain medication reporting, the indications are strongly in favor of a targeted resistance program to limit strength deficiencies post op. The second study18 found maximal strength training led to improved muscle strength and reduced postural sway in THA patients during activities of daily living. While limited by an insufficiently powered sample size and the absence of preoperative gait data, notable statistical differences in postural sway were detected in favor of the intervention group immediately post study.

Another study17 examined progressive strengthening of the quadriceps in a six-week TKA post-surgical hypertrophy protocol which included exercises that targeted the hip abductors, hip flexors, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius. Significant increases in strength occurred within those six weeks. A second study19 examined an eight week post-surgical TKA hypertrophy protocol whereby muscle strength within the intervention group significantly increased leg press (37%), and knee extension (43%) strength.

Atrophic musculature is a common occurrence following THA. Nankaku et al.20 measured hip abductor and knee extensor strengths prior to undergoing unilateral THA and found a correlation between preoperative weakness of the gluteus medius and postoperative limping during gait. The gluteal musculature, in particular, the gluteus medius has been shown to be the primary hip stabiliser during single legged functional movements such as gait.21 Through this analysis of the literature pertaining to atrophic musculature surrounding the hip, it can be concluded that hip abductor and knee extensor strengthening are integral parts of early exercise following THA as they assist to provide stabilization of the hips during gait and enhance stability of the pelvis during standing.22

A typical hypertrophy protocol consists of a combination of mechanical and metabolic stresses with dosage ranging between 3-6 sets of 8-12 repetitions with short rest intervals of 60 seconds or less. The intensity should be of moderate effort at 60-80% of 1RM with subsequent increases in training volume each week. Research has shown that a standard hypertrophy training program ranges from 4-12 weeks depending on an individual’s goals. Hypertrophy is the most effective method to strengthen and increase the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the musculature.23

The conclusions of this review were limited by the availability of research specifically on anterior approach THA, hypertrophy training post THA, and the diversity of interventions, durations, age of participants, intervention specificity and wide variety of outcomes utilized across the selected studies. This ultimately results in a lack of clarity regarding the ability to compare among rehab programs to determine effectiveness or the optimal program.

Conclusion

This review of the available literature of post operative THA and TKA protocols indicates that there are some inconsistencies that provide grounds to direct further research into postoperative THA muscular hypertrophy training programs. There is no consensus for the best practice regarding a hypertrophy program following THA. This is especially true for anterior direct anterior techniques in conjunction with hypertrophy protocols in which this search found zero results. To address the apparent gaps in the literature, there is a need for well conducted studies that address rehabilitation specifically for hypertrophy in the contexts of anterior hip surgery, THA in younger populations, and return to sport following THA. It will also be important to discern if utilizing standardized intervention protocols and outcome measures benefit those wishing to return to high level activities after THA. The literature that was reviewed suggests that interventions post TKA and THA are both safe and effective in achieving strength outcomes necessary to combat strength asymmetries and deficiencies.