INTRODUCTION

Injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is common in sports, with an estimated 68.6 ACL injuries per 100,000 person-years in the USA.1 Surgical reconstruction of the torn ligament is the preferred management method for isolated ACL tears.2 Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) is followed by extensive rehabilitation focused on physical impairments and functional outcomes,3 which can last up to nine months and aims for a timely return to sports.3 Another goal of ACLR rehabilitation is to achieve the pre-injury level of physical performance. However, only 55% of participants are able to return to competitive sports.4 Physical activity is crucial for overall health, as it reduces the risk of non-communicable diseases.5 A general decrease in the level of physical activity is reported among people in the years following ACLR6 which is further associated with an increase in other health-related problems, such as obesity and high blood pressure,7 and early onset of osteoarthritis, which overall, increases the burden on the healthcare system.8 Overall, these long-term complications and reduced activity levels influences the quality of life,9 affecting general health and well-being in individuals with ACLR.10,11

A sports injury has both physical and psychological consequences for an athlete.12 The structure of most rehabilitation protocols is to resolve physical post-operative impairments followed by progression to exercises that mimic sports activities.13 This approach is successful for many athletes; however, not for all. For instance, many patients achieve functional milestones but still do not return to sports, and fear of reinjury is a primary reason.14 However, psychological concerns are frequently underassessed and undertreated within standard ACLR rehabilitation protocols by clinicians.15 Kinesiophobia, defined as the fear of movement is often elevated in patients who do not return to sport and places them at high risk of experiencing secondary ACL injury.16 Also, individuals with high kinesiophobia post-surgery tend to have lower physical activity levels, poorer self-reported knee function, and a lower return-to-sport rate compared to those with low kinesiophobia.17,18 Patients with high kinesiophobia also achieve clinical milestones later compared to those with low kinesiophobia.19 There is a strong need to understand how to identify patients with kinesiophobia early during rehabilitation so that their psychological concerns can be addressed; however, current practice lacks standards for this.

Objective scales, such as the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia,20 are available to assess the level of kinesiophobia in participants during rehabilitation. The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia-11 (TSK-11), is a shortened version adapted from the original TSK-17 is one method used to assess kinesiophobia. While the TSK-11 can assess or measure the presence and severity of kinesiophobia, it may not identify which specific component or dimension of that fear should be addressed in treatment with an individual athlete. Inquiry through open-ended questions might help to understand the specific fears that need to be addressed or the reasons for not having fears in individuals with low kinesiophobia. Identifying the key themes from qualitative study can provide the foundation for determining the targets of interventions to address the psychological needs of struggling patients. This knowledge is critical for clinicians, researchers, and other health professionals to develop effective interventions. Further, including participants across the kinesiophobia spectrum provides complementary insights: those with higher kinesiophobia reveal avoidance behaviors and barriers to return to sport, while those with lower kinesiophobia highlight motivations and facilitators that supported their recovery.

Therefore, the purpose of this mixed-methods study was to describe the perspectives on rehabilitation and recovery in patients following ACLR categorized as having high or low kinesiophobia, and to compare their activity, function, and psychological status. It was hypothesized that participants with low versus high kinesiophobia after ACLR would demonstrate differences in psychological vulnerability, resilience levels, and knee function as reported by self-reported outcome measures.

METHODS

Participants and Study Design

This was a mixed methods study. Participants completed patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures (quantitative data) and participated in face-to-face semi-structured interviews (qualitative data).

A purposive sampling strategy was used to identify participants from a clinical data set of patients at the University of Virginia Exercise and Sports Injury Lab (Lower Extremity Assessment Program study). The database includes patients with primary and revision ACLR (any graft type) with or without associated ligamentous, meniscal, or chondral injury. These patients were referred for postoperative assessments that included muscle strength testing, functional performance tests, and PROs. The study protocol was approved by the University of Virginia Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Physically active participants aged 18-30 years and 5-12 months post-ACLR, actively engaged in rehabilitation, took part in the study. Most of the participants had not returned to their sports. This time range was chosen because it corresponds with a return to activity phase of rehabilitation, whereby rehabilitation is aimed at returning the patient to previous activity levels and where reinjury fear peaks.21 Participants with English as a second language were excluded from the study.

Procedures

The TSK-11 was used to assess kinesiophobia and stratify participants into two groups based on their scores.20 Previous research has identified scores over 17 on the TSK-11 as signifying a person experiencing a high fear of re-injury.22 Participants were categorized into either high kinesiophobia (TSK-11 >17) or low kinesiophobia (TSK-11 ≤17) groups. Participants were enrolled until data saturation was reached for each group separately in the qualitative portion of the study, meaning enrollment continued until no new themes or insights emerged from additional interviews.

Participants completed a demographic questionnaire that included their age, sex, weight, and the date of their surgery, and patient-reported outcomes (PRO) including the Tegner Activity Scale,23 the Marx Activity Scale,24 and the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scale (KOOS),25 the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC),26 the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Return to Sports Index (ACL-RSI),27 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7).28

The Tegner Activity Scale is a one-item score that grades activity based on work and sports activities, ranging from 0 to 10. Zero represents disability due to knee problems, and 10 represents a national or international level player.23 Participants reported their ‘before injury’ and ‘current’ physical activity levels during the study.

The Marx Activity Scale is based on specific knee functions and frequency of participation. Each of four knee functions (running, cutting, decelerating, and pivoting) is rated on a five-point scale of frequency (<1 time in a month, 1 time/month, 1 time in a week, 2 or 3 times in a week, or 4 or more times a week) and scored between 0 and 4. The scale is scored by adding the scores to give a total out of a possible 16 points, with a higher score indicating more frequent participation.24

The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Score (KOOS) measures patients’ opinions about their knee and associated problems such as ligamentous injuries.29 It has five subscales: (1) pain, (2) symptoms, (3) function during activities of daily living, (4) sport and recreational function, and (5) knee-related quality of life. Each subscale is scored separately on a scale from 0% to 100%, where higher values indicate better knee function. KOOS subscales have good reliability and validity in patients with knee injuries. Of particular interest in this study, the minimally clinically important difference for the KOOS quality of life subscale is 8 points.29,30

The International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective form measures regional knee health in terms of knee function and is reliable and valid for assessing knee ligamentous injuries.26 Scores range from 0 to 100, where 100 indicates that a patient has no limitation with daily or sporting activities and an absence of symptoms.19 The IKDC demonstrates good internal consistency and test-retest reliability in patients with ACLR.26

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament - Return to Sport after Injury (ACL-RSI) scale is a reliable and valid 12-item questionnaire to assess psychological readiness for sports participation in the domains of emotion, confidence in performance, and risk appraisal.27 The scale ranges from 1 to 10, with higher scores indicating a more positive psychological response. The total score is determined by adding the values of the 12 responses and then calculating their relationship to 100 to obtain a percentage.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale is a brief, self-report questionnaire used to assess anxiety symptoms, with a score of 10 or higher suggesting a potential diagnosis of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD).31 This was included to assess because anxiety can negatively impact recovery and return to sport, and early identification allows for timely interventions to improve outcomes.32

Qualitative Interviews

All interviews were conducted individually via Zoom by two researchers who were not blinded to the participants’ level of kinesiophobia. MK (physical therapist), who has clinical experience of 4.5 years in musculoskeletal rehabilitation and experience conducting and publishing qualitative research studies, served as the primary interviewer for all interviews. LV (athletic trainer), who has clinical experience of 28 years and involvement in conducting qualitative studies, participated as a co-interviewer in alternating interviews.

The interviews were conducted using an interview guide consisting of open-ended and follow up questions (Table 1) developed and refined by the research team. Interviews began with brief introductions of the research team and stating the purpose of the interview. Following that participants were asked about their injury onset, their rehabilitation journey, challenges, and the present situation. While the guide provided structure, the selection and wording of specific questions and their respective order depended on how the interview proceeded. Field notes were taken during and after the interview. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The sample size was based on data saturation for each group separately.33 To determine data saturation, new participants were recruited and interviewed until no new themes emerged from the transcription. Once data saturation occurred, two more interviews were conducted to verify that no new themes emerged from those interviews.33 Recruitment was stopped following that. The trustworthiness and dependability of the data were established through the parallel coding of every alternative interview by a second researcher. The confirmability of the study findings was ensured through an open discussion within the research team following the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses (median and ranges) were performed for the patient-reported outcomes. Due to non-normality of data, Mann-Whitney tests were used to determine examine differences PRO scores among the groups. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d to assess the magnitude of differences between groups.34 Effect sizes were interpreted as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), or large (d = 0.8) according to established conventions.34

Qualitative data were collated using an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Office 2019). The general inductive method was used for analysis of the interview data.35 In this method, the transcriptions were read multiple times, and text segments reflecting the participants’ experiences are identified and coded by two researchers in the team independently. The codes were categorized, and the researcher’s developed links between these categories and identified the themes relevant to the research aims. The categories and emerging themes and sub-themes were discussed and confirmed by the research team. Quotes and themes were used to analyze the unique and common themes among both groups.

RESULTS

Nine participants (5 women) were placed in the high kinesiophobia group and six participants (4 women) in the low kinesiophobia group. There were no statistically significant demographic differences between the groups in (Table 2). Participants were at a lower level of physical activity compared to their pre-injury level based on the Tegner scores, although not significantly different between groups. (Table 2)

The TSK-11 score was significantly different between groups (high kinesiophobia = 25.0, range (18-30); low kinesiophobia = 13.5 (12-15), (P= 0.001)(Table 3). The only other statistically significant difference in patients’ reported outcomes was in the KOOS quality of life subscale (high kinesiophobia= 56.3 (37.5-81.3); low kinesiophobia= 71.9 (62.5-75.0); P=0.012). The 15.6-point difference between groups exceeded the established MCID of 8 points by nearly two-fold, indicating a clinically meaningful difference. Notably, while other KOOS subscales (pain, symptoms, sports function, and ADL) showed numerical differences favoring the low kinesiophobia group, none reached statistical significance. (Table 2). The difference in ACL-RSI scores between the high kinesiophobia (Mean = 44.9) and low kinesiophobia (Mean = 71.2) groups, while not statistically significantly different (p = 0.059), exceeded the established MCID of 9-10 points by more than 2.5-fold, with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.39).

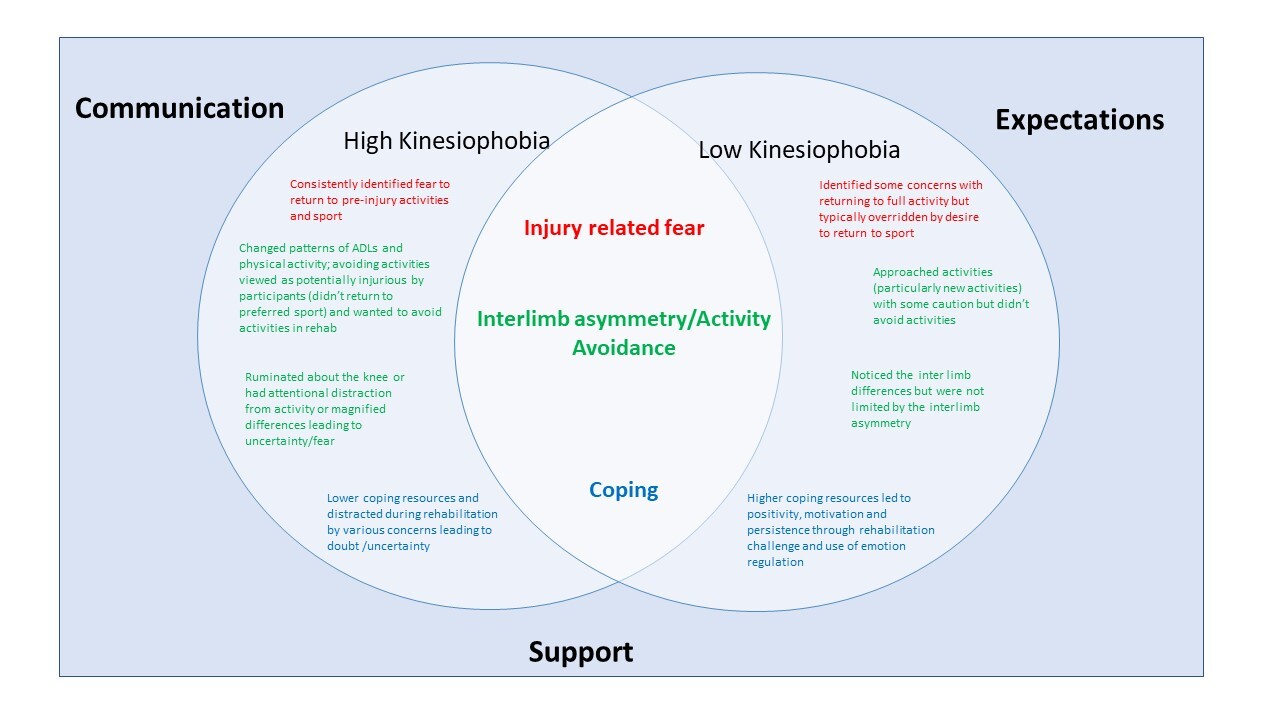

Participants took between 17 minutes to 50 minutes to complete the interview. No interview was repeated. Initial coding was used on the interview transcriptions, which were then condensed into 10 sub-themes that portrayed the most common concerns. These sub-themes were then grouped into three major themes: (1) fear of re-injury, (2) interlimb asymmetry and activity avoidance, and (3) coping mechanisms. Participants were assigned alphanumeric codes (e.g., DR_06) to maintain confidentiality, and these codes are used throughout the results when presenting quotations. Example quotes for each theme are presented in Table 4. An expanded list of quotes supporting theme and subthemes are presented in Appendix 1.

The themes of the study are be depicted in Figure 1. As demonstrated in the figure, patients experience and go through a similar journey and encounter injury-related fear, activity avoidance and interlimb asymmetry, and develop coping strategies whether they are high or low scorers on the TSK-11 However, these themes can be viewed on a spectrum ranging from mild to extreme within each group. For example, participants in the high kinesiophobia group identified a fear of returning to pre-injury activities and sports, whereas participants in the low kinesiophobia group also identified some concerns regarding returning to full activity. However, these concerns were outweighed by a strong desire to return to sports among participants with low kinesiophobia. Similarly, activity avoidance was one of the themes where participants with high kinesiophobia changed and avoided some of the activities of daily living, while participants with low kinesiophobia were only cautious about certain new activities. Both groups noted interlimb asymmetry as a concern; participants in high kinesiophobia seemed to magnify the differences, leading to uncertainty and fear, while participants in low kinesiophobia did not seem to be limited by these differences. Coping strategies differed between groups such that participants with high kinesiophobia seemed to be using less coping strategies and seemed to have multiple concerns leading to uncertainty, whereas participants with low kinesiophobia used coping strategies that seemed to lead to positivity, motivation, and persistence through the rehabilitation.

Theme 1: Injury Related Fears

All participants described experiencing injury-related fear regarding the knee which appeared related to several factors (sub-themes): Concern about the future knee health; Low confidence in the knee; Toll of rehabilitation process; Mental hurdles related to mechanism of injury.

Concern with the future outcome

Participants across both groups expressed concerns about re-injury, though these manifested differently. The majority of participants worried about the future health of their knee, particularly the increased risk of developing osteoarthritis or requiring total knee arthroplasty early in life. One participant in the high kinesiophobia group described not feeling ready to return to contact sports, expressing worry that game situations could lead to re-injury (quote 1, Table 4). In contrast, a participant in the low kinesiophobia group acknowledged concerns but emphasized wanting a physically stable knee rather than being driven by fear or anxiety (quote 2).

Confidence in the reconstructed knee

Several participants displayed low confidence in their reconstructed knee and in their ability to perform at pre-injury levels. Participants in the high kinesiophobia group described avoiding activities in which they lacked confidence. For example, one participant explained attempting sport-like activities but feeling uncomfortable with the knee’s response (quote 3). Participants in the low kinesiophobia group also noted confidence issues but framed them as part of an active rebuilding process, such as one participant who reported working to build confidence in jumping movements (quote 4).

The toll of the rehabilitation process

The majority of participants described the rehabilitation process as lengthy and difficult, both mentally and physically. The prospect of experiencing rehabilitation again contributed to injury-related fear. A participant in the high kinesiophobia group expressed fear of having another surgery or enduring the lengthy rehabilitation process again (quote 5). Similarly, a participant in the low kinesiophobia group described feeling unprepared for the difficulty level and noted the challenge of losing their athletic identity due to post-surgical restrictions (quote 6).

Mental hurdles related to mechanism of injury

Several participants discussed fear related to movements similar to their injury mechanism, particularly as rehabilitation intensity increased with cutting and jumping activities. One participant in the high kinesiophobia group identified this as their most concerning issue (quote 7). A participant in the low kinesiophobia group described initial fear with single-leg hopping but noted that proper form helped overcome this fear (quote 8).

Theme 2: Activity Avoidance and interlimb Asymmetry

All participants reported avoiding certain activities, especially sports-related movements. Participants noted differences in strength and mobility between limbs and often favored the uninjured limb when the affected limb felt fatigued. These asymmetries were frequently associated with activity avoidance or perceived pain.

Perceived pain during movement

Several participants in both groups experienced pain during movement, though their responses differed. Participants in the high kinesiophobia group more often allowed pain to limit their activities. One participant described out-of-proportion pain leading to avoidance of activities such as cycling and rehabilitation exercises (quote 9). In contrast, participants in the low kinesiophobia group typically continued activities despite experiencing some pain, with one participant noting knee pain but maintaining their rehabilitation program (quote 10).

Hesitancy during Performance

The majority of participants in the high kinesiophobia group displayed hesitancy during performance, with one describing extreme reluctance to perform a single-leg box jump even under physical therapist supervision (quote 11). Fewer participants in the low kinesiophobia group discussed hesitancy, with one attributing it primarily to physical strength concerns rather than fear of re-injury (quote 12).

Perceived strength and mobility deficits

Participants across both groups recognized strength and mobility deficits in the reconstructed knee. A participant in the high kinesiophobia group noted compensating with the unaffected side during cutting motions (quote 13). A participant in the low kinesiophobia group described making conscious efforts to correct weight-shifting patterns during exercise (quote 14).

Theme 3: Coping Mechanisms

Participants in both groups experienced different levels of positive coping throughout the rehabilitation process, but the mechanisms used varied widely within and between both groups. Participants discussed their motivational factors and the level of support they received from friends and family. Participants in the high kinesiophobia group displayed a higher utilization of support than the participants in the low kinesiophobia group. Lastly, strategies to help with the physical and mental roadblocks were discussed.

Motivating factors

Participants in both groups experienced varying levels of positive coping throughout rehabilitation, though mechanisms differed considerably. Several participants identified motivating factors that sustained them through rehabilitation. A participant in the high kinesiophobia group cited encouragement from their physical therapist as a significant motivator (quote 15). A participant in the low kinesiophobia group described their professional athletic aspirations and the sacrifices they had made to their sport as primary motivation (quote 16).

Support system

Several participants recognized the importance of their support systems, including physical therapists, friends, family, and teammates. A participant in the high kinesiophobia group credited their girlfriend as essential to completing rehabilitation (quote 17). A participant in the low kinesiophobia group described how family encouragement to try yoga, combined with teammates joining the activity, provided valuable support while regaining knee strength (quote 18).

Strategies for mental/physical roadblocks

The majority of participants discussed strategies for managing mental and physical roadblocks. A participant in the high kinesiophobia group emphasized the value of patience and trust in the rehabilitation process (quote 19). A participant in the low kinesiophobia group wished for more pre-surgical education about the rehabilitation process’s intensity and duration (quote 20).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this mixed-methods study was to describe the perspectives on rehabilitation and recovery in patients following ACLR categorized as having high or low kinesiophobia, and to compare their activity, function, and psychological status using patient-reported outcomes and semi-structured interviews.

The 26.3-point difference in ACL-RSI scores between groups, with a large effect size (Cohen’s d=1.39) represents a clinically meaningful gap in psychological readiness to return to sport that exceeded the established MCID of 9-10 points by more than 2.5-fold. Notably, the high kinesiophobia group’s mean score fell below the critical threshold of 56, which has been associated with successful return to sport, while the low kinesiophobia group exceeded this benchmark. These findings underscore the substantial impact of kinesiophobia on psychological readiness and suggest that patients with high kinesiophobia may require targeted psychological interventions to improve readiness for return to sport. The lack of statistically significant difference in scores between groups (p = 0.059) likely reflects limited statistical power due to small sample size (n = 15) rather than absence of a true clinical difference.

A significant difference in KOOS quality of life scores between groups (15.6 points, p=0.012) provides important context for understanding the broader impact of kinesiophobia on patients’ lives beyond physical function. The quality of life subscale captures patients’ overall knee-related concerns, lifestyle modifications, and confidence—constructs that align closely with the qualitative themes of injury-related fear and activity avoidance identified in this study. While physical function measures (KOOS ADL, KOOS Sports, IKDC) showed numerical differences between groups that were not significantly different, the substantial difference in quality of life subscale score suggests that kinesiophobia’s primary impact may be on psychological well-being and perceived limitations rather than objective physical capabilities at this stage of recovery. This finding reinforces that addressing kinesiophobia requires attention to both physical rehabilitation and psychosocial factors that influence how patients perceive and interact with their reconstructed knee in daily life. The lack of significant differences in other KOOS subscales (pain, symptoms, ADL, sports function) despite the large quality of life difference further emphasizes the disconnect between physical capacity and psychological readiness that characterizes high kinesiophobia.

The most common theme discovered among the participants was injury-related fear. Overall, the degree to which participants feared injury varied widely among the two groups. Participants in both groups seemed to be experiencing injury-related fears. Participants with low kinesiophobia explained frustration with being away from the sports that they felt were a part of their identity. These participants also seemed more motivated to return to pre-injury levels and wanted to continue playing the sports without concern for re-injury. Other participants with low fear were done with high-level sports due to graduation; therefore, they were not as concerned with returning to pre-injury levels but rather just wanted to regain full function for activities of daily living. On the other hand, participants with high fear described high levels of activity avoidance and caution. Elevated levels of fear have also been noted in another study, which reported an association between fear of reinjury and protected movement and activation patterns among patients two years after surgery.36 Athletes with a high fear of reinjury may reduce exposure to physical activities, which leads to an athlete’s perception of low function.37 This association between fear and maladaptive movement patterns needs to be addressed by clinicians early on as it can predispose the patients to re-injury.

Activity avoidance and interlimb asymmetry were highly linked throughout the interviews. Participants described avoiding the use of their injured knee during day-to-day functional tasks. Certain participants described avoiding jumping off the injured leg though that was their dominant leg. Other participants noted the development of a limp, even in the absence of knee pain. Some participants described favoring the uninjured leg during exercises such as squats and even going up and downstairs. This limb avoidance pattern can lead to maladaptive behavior among participants, causing them to start avoiding loading on the injured side. Athletes with asymmetrical movement patterns at the hip and knee 1-year post-surgery are at least three times more likely to experience a second ACL injury than those without asymmetries.15 Noticing and addressing these movement asymmetries early in the rehabilitation process is extremely important for restoring the optimal movement pattern. These altered movement patterns can potentially lead to the onset and progression of osteoarthritis.38 A previous study has indicated that asymmetrical loading (i.e., underloading the surgical limb) during gait early after ACL injury and six months after ACLR were associated with radiographic signs of osteoarthritis five years after surgery.39

Coping, in psychology, refers to the cognitive and behavioral efforts people use to manage stressful or challenging situations, aiming to reduce stress and its negative effects.40 Individuals exhibit significant differences in coping strategies when faced with stressful situations.41 In the current study, coping mechanisms (the psychological processes used to manage stress) varied widely among the participants. Participants in the high kinesiophobia group reported using fewer coping resources (the available supports and tools, such as social networks or access to therapy) during the rehabilitation could lead to feelings of doubt and uncertainty about rehabilitation progression, and this was more apparent in high kinesiophobia group participants. In contrast, participants in the low kinesiophobia group expressed utilizing coping resources lead to positivity, motivation, and persistence through the rehabilitation process. The use of coping strategies (specific techniques or actions, such as positive reframing) is known to improve return to sport and reduce fear of re-injury.42 Participants with high kinesiophobia and fewer coping strategies are important to recognize as these behavioral patterns can ultimately increase feelings of depression and anxiety among participants. Higher kinesiophobia, along with lower coping patterns, can slow down the progression during the rehabilitation.

Lower participation in sports and poor quality of life in the high kinesiophobia group is concerning. This can persist up to five years post-surgery.10 Poor quality of life and high fears of re-injury were reported up to 10 years postoperatively by another study.43 This can lead to lower levels of satisfaction and lower physical activity levels.18 Physical therapists and athletic trainers can help participants by identifying these themes in patients to provide needed support. It is well known that having a positive support system can lead to improved outcomes; therefore, the authors recommend incorporating supportive techniques into the rehabilitation process. While use of reliable and valid questionnaires such as TSK-11 can help identify the patients, however, subjectively noticing confidence while patients perform the movements during the rehabilitation can be helpful. Interventions such as psychologically informed practices, including cognitive behavioral therapy, graded exposure, and or referral to psychologists may help patients.44

Limitations

As with any study there are strengths and limitations. The small sample size is a limitation of this study that likely reduced statistical power to detect significant differences in quantitative patient-reported outcomes. However, the primary aim of this mixed-methods study was to explore qualitative themes and experiences through in-depth interviews, with sample size determined by data saturation rather than statistical power calculations for quantitative comparisons. The enrollment of participants continued until thematic saturation was achieved in each group separately, which is an appropriate methodology for the qualitative component but may have limited the ability to detect all statistically significant differences in PROs. Future studies with larger sample sizes adequately powered for quantitative analysis would be valuable to confirm the preliminary quantitative findings presented here. Interviewers were not blinded to the participants’ level of kinesiophobia and their group. As both groups were interviewed using the same interview guide, the authors believe that that lack of blinding had any impact on study results. Also, it should be noted that while kinesiophobia and resilience are related psychological constructs, they are distinct. Low kinesiophobia reflects reduced fear of movement, whereas resilience encompasses broader adaptive capacity. Future research should examine how these constructs interact during ACL rehabilitation. Lastly, the wide range of time from surgery (5-11 months) is a limitation, as participants may have been at different rehabilitation stages with varying psychological needs. Kinesiophobia and coping mechanisms may manifest differently depending on where individuals are in their recovery journey, making it difficult to isolate the impact of kinesiophobia level from rehabilitation stage. Future research should examine narrower post-operative time windows or use longitudinal designs to track how psychological factors evolve throughout rehabilitation Participants included in the study were up to 12 months post-surgery; this may limit the generalizability of the study findings for those at later stages post-rehabilitation. These findings provide insights into the experiences of individuals following ACLR within the United States healthcare context and may inform clinical practice in physical rehabilitation settings.

CONCLUSIONS

Significant differences in KOOS quality of life scores were found between high and low kinesiophobia groups following ACLR, highlighting the importance of assessing psychosocial well-being alongside physical outcomes. Injury-related fear, activity avoidance, and coping mechanisms were common themes across participants, though they manifested differently between high and low kinesiophobia groups. It appears that patients may demonstrate adequate physical progress while experiencing perceived substantial deficits in knee-related quality of life. These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of psychological factors in ACLR recovery and suggest that kinesiophobia assessment may provide valuable information beyond traditional physical measures when evaluating patient recovery status

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This study was funded by Curry IDEAs (Innovative, Developmental, Exploratory Awards)- University of Virginia

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.